In his much-anticipated follow-up to his New York Times bestseller Endure, Alex Hutchinson’s new book dives deep into exploration and why — whether it’s trying a new restaurant, changing careers, or deciding to run a marathon — it’s an essential ingredient of human life. More than just a need to get outside, Alex argues that the search for the unknown is a primal urge that has shaped the history of our species and continues to mold our behaviour in ways we are only beginning to understand.

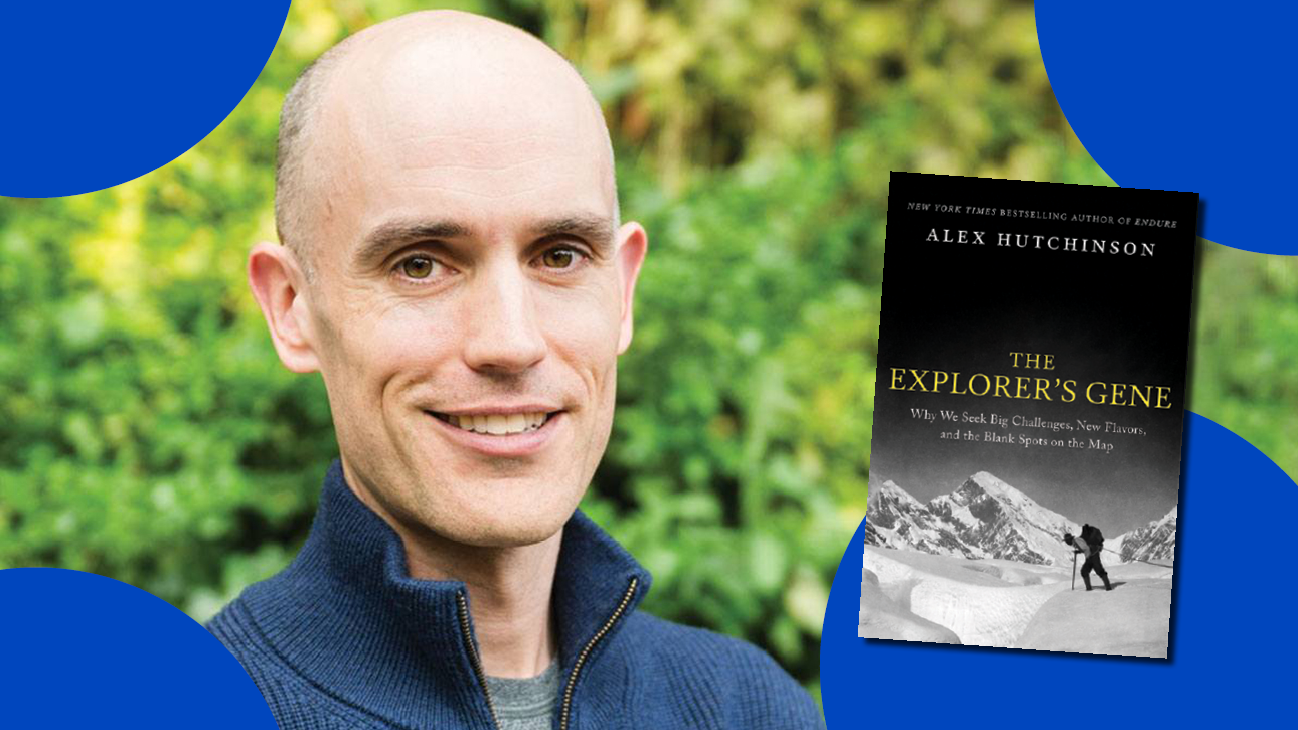

Alex is an award-winning science journalist and Outside magazine’s longtime Sweat Science columnist. Before journalism, he was a postdoctoral physicist and a long-distance runner for the Canadian national team. His new book, The Explorer’s Gene: Why We Seek Big Challenges, New Flavors, and the Blank Spots on the Map, combines riveting stories of exploration with cutting-edge insights from behavioural psychology and neuroscience to make a powerful case that our lives are better — more productive, more meaningful, and more fun — when we break our habits and chart a new path.

We recently sat down with Alex to discuss his new book in more detail and discover why curiosity and exploration aren’t merely a hobby, but a core part of the human experience.

A Biological Need to Explore

Speakers Spotlight: In your book description, you say that exploration is part of our biological makeup. How are we hard-wired to explore?

Alex Hutchinson: There’s an idea in neuroscience called the Free Energy Principle, which basically says that our brains are wired to minimize surprise. The best way to minimize surprise, in the long term, is to be unquenchably curious about the world so that you learn as much as possible about how it works and what’s out there. That’s ultimately why humans ended up spreading to every habitable point on the globe, and it’s also why we can’t help wondering what’s over the horizon.

The Explorer’s Gene in Everyday Life

SpSp: We often think of exploration in grand, historic terms — mountains climbed, continents crossed. But you argue that the same impulse shows up in everyday decisions. What are some surprising ways the explorer’s gene reveals itself in our modern lives?

AH: The classic example that researchers who study exploring use is ordering in a restaurant. Do you stick with the pasta dish you usually order or do you try the special? Amazingly, scientists analyzing huge datasets from food-delivery companies have found that when people are choosing between two similar restaurants, they have a slight bias in favour of the one they know less about. It’s that explorer’s gene in action!

That may seem like a trivial example, but these sorts of decisions show up all over the place: choosing whether to get married or keep dating, weighing job offers, investing in R&D instead of marketing. The common thread is that you’re opting for a choice whose outcome you think might be better than what you’ve got, while accepting the possibility that it might be worse.

The Neuroscience Behind Discovery

SpSp: You write that exploration makes life more meaningful, productive, and fun. Can you walk us through what’s happening in our brains when we break a habit or step into the unknown?

AH: From the brain’s point of view, breaking a habit is hard work. The whole point of habits is that they can help us run on autopilot; stepping into the unknown forces you to engage your senses and sweat the details.

That may sound like a less productive mode, and in the short term it often is. But in the long term, the extra cognitive effort pays off. For example, the food-delivery data shows that ordering from an unfamiliar restaurant typically leads to a worse-than-usual meal. But if you stick with it and keep trying new restaurants anyway, your average rating will increase over time as you discover some hidden gems and discard the duds. That’s where the productivity gains come in, but also where people tend to go wrong: you have to be willing to accept some short-term pain in order to get the long-term gains.

The Connection Between Endurance and Exploration

SpSp: This book is a follow-up to your bestseller, Endure, where you wrote extensively about human limits. Is there a connection between how we push through pain and how we seek out the unfamiliar?

AH: Definitely! If Endure was about how we push our limits, The Explorer’s Gene is in some ways about why we push them. Choosing to take on a really difficult challenge, whether it’s running a marathon or starting a business, might seem irrational, but it’s basically a way of exploring our own capacities. We do hard things to find out whether we can do them.

But it’s not just about satisfying curiosity. We tend to find hard things rewarding, an effect that psychologists call the “effort paradox.” Climbing mountains, running marathons, buying furniture from IKEA, even raising children — these are all difficult, but people tend to find them meaningful. So, I think one reason some people are drawn to exploring is — counterintuitively — that it’s hard.

Modern Frontiers of Discovery

SpSp: In your book, you challenge the idea that there’s nothing left to discover in our fully mapped digital world. How do you define discovery today, and what are some frontiers that still excite you?

AH: You can define exploring in various ways. At one end of the spectrum, it’s doing something that no one has ever done before. That doesn’t apply to many of us. At the other end, you could say it’s exploring anytime you try something new, like changing the channel on your TV. That’s a pretty trivial definition. The exploring I’m talking about is somewhere between those extremes, and generally ticks three boxes: it’s fun, hard, and has an uncertain outcome.

Before I became a journalist, I worked in physics, so I’m still interested in the deep questions physicists are exploring like why it is that electrons can be in two places at once but baseballs can’t (or, to put it another way, what defines the boundary between quantum mechanics and everyday life). But what I’m most interested in these days is more personal forms of exploration. There’s nothing I love better than being in the mountains, heading up a pass with no idea what lies on the other side — even if thousands of people have been there before me.

How to Activate Your Inner Explorer

SpSp: For those feeling stuck or stagnant, what’s one small way to activate their inner explorer right now?

AH: Here’s an easy one: turn off the turn-by-turn directions on your phone. Maybe not all the time, but when you have a rough idea of where you’re going, or when you want to wander around a new city, or when you’ve got enough time that it doesn’t matter if you get a little bit lost. You’ll find that navigating the old-fashioned way forces you to be more present in your surroundings — it’s like being the driver of a car rather than the passenger. And you’ve still got the phone in your pocket, so if you do get lost it’s not a disaster, it’s an adventure!

Hire Alex Hutchinson to Speak at Your Event

Ready to inspire your team to push beyond their limits and embrace the unknown? Alex Hutchinson brings the same compelling insights from his bestselling books, The Explorer’s Gene and Endure, to the stage, helping audiences unlock their potential through the science of human performance and exploration.

Contact us to learn more about Alex and the ways he can transform how your team approaches challenges and discovers new possibilities.