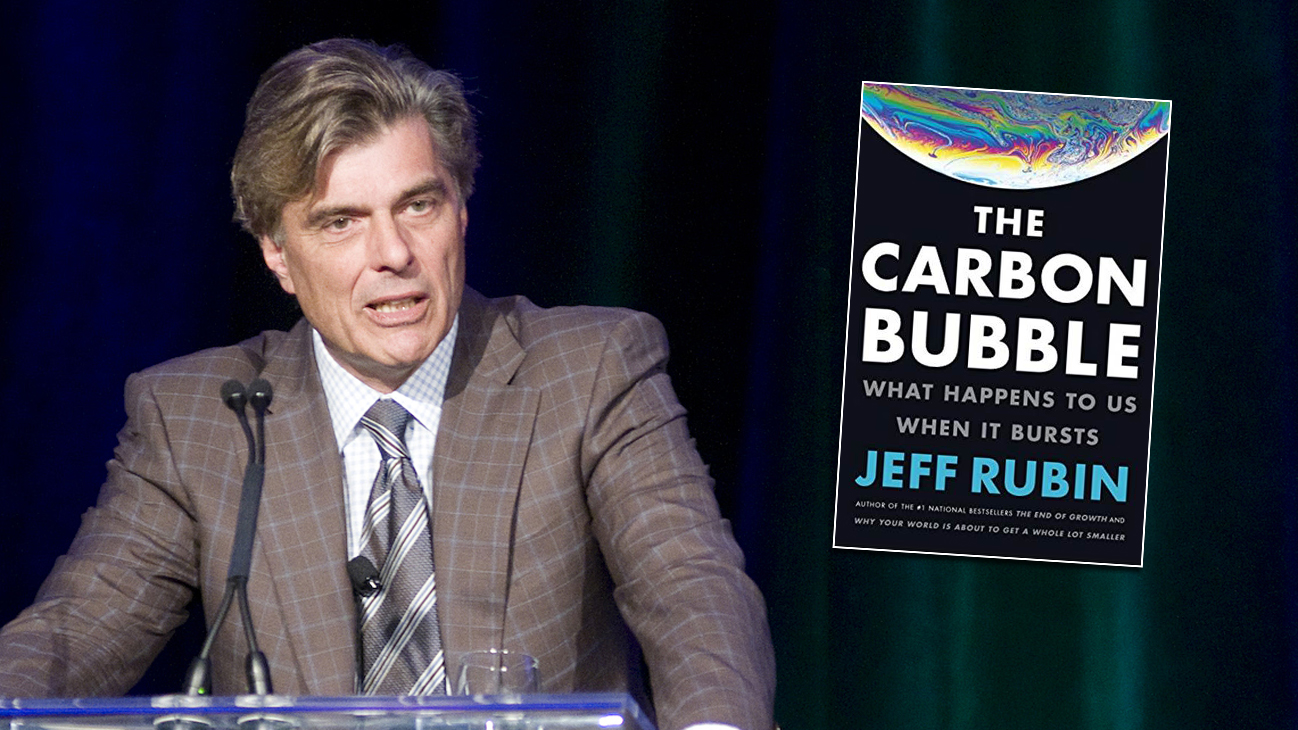

In The Carbon Bubble, Jeff Rubin explores how the very climate change that will leave much of the country’s carbon unburnable could at the same time make some of Canada’s other resource assets more valuable: our water and our land. Rubin was chief economist and chief strategist at CIBC World Markets where he worked for over 20 years. Below, Jeff writes with David Suzuki for The Globe and Mail on how Stephen Harper’s “carbon-fuelled energy agenda hasn’t worked out”:

As Canadians prepare to vote in an upcoming federal election, it’s time to reassess the country’s economic prospects, once touted as the strong suit of Stephen Harper’s government. For almost a decade, Canadians have been told massive expansion of Alberta’s oil sands would be the engine of economic growth as the country rode a wave of soaring oil prices during the government’s early years. Some question the wisdom of building an economy on the foundation of a single resource. And the Prime Minister’s strategy of making Canada an oil-based energy superpower has led instead to a made-in-Canada recession, with a dramatic implosion in capital spending in the country’s oil patch.

To avoid confronting real concerns about human-caused climate change, the Harper government took the unprecedented path of cancelling Canada’s commitment to the international Kyoto agreement, suppressing potential obstructions to Canada’s petroleum path, shutting down environmental programs, laying off hundreds of government scientists, discarding scientific information from government libraries and decreeing that government must vet all research before scientists are allowed to speak publicly or publish. Science forfeits all credibility when it is fettered by ideological lenses.

It makes no sense for any government focused on the economy to ignore the accelerating issue of climate change. Canada is a northern country where temperatures are already climbing rapidly. We have the world’s longest marine coastline, which will be heavily affected by sea-level rise, and much of the national economy is built around such climate-sensitive areas as agriculture, forestry, fisheries, tourism and winter sports. Add the costs of floods, drought, massive fires and more, and you have a recipe for economic failure. One of Britain’s leading economists, Sir Nicholas Stern, calls climate change the “greatest market failure in history,” and concludes that failing to act to reduce greenhouse gas emissions will be economically disastrous.

Much can happen over the course of a government’s mandate, especially one that has spanned three elections. One by one, the key assumptions behind the Harper government’s economic strategy of oil-based growth have fallen by the wayside. Initially, it was the assumption of strong demand from the U.S. market and its need for secure oil supplies from a friendly neighbour that drove Canada’s aggressive oil ambitions. But the high prices that lifted bitumen out of the oil sands also allowed “tight oil” to be fracked from U.S. shale formations like the Bakkan and Eagle Ford, which suddenly obviated the need for importing higher-cost Canadian oil.

Next, ambitious oil-sands expansion was based on the assumption of never-ending double-digit growth in China’s economy and that country’s insatiable fuel demand. But the very triple-digit oil prices that enabled development of high-cost supply like the oil sands also curtailed economic growth and fuel demand, nowhere more so than in China itself. Judging by China’s energy consumption, its economy is growing at about half its previous double-digit rate.

That has left the oil sands in a world of sluggish economic growth, a glutted global oil market and, worst of all, plunging oil prices. Suddenly the country’s government-driven engine of economic growth looks more and more like stranded assets. The ambitious expansion plans that would have seen production more than double in the next decade and a half are no longer commercially viable. Even with the long-sought-after world oil prices, new oil-sands projects don’t make any economic sense, let alone with the deeply discounted oil price (Western Canadian Select) most oil-sands producers receive.

The tens of billions of dollars of cancelled investment in oil-sands projects profoundly changes the national debate Canadians have been having about the supposedly urgent economic need for new pipelines. While the federal government continues to lobby hard for them, citing the critical need to get bitumen to tidewater and foreign markets, the reality is that an oversupplied world oil market doesn’t need Canada’s high-cost fuel. The very projects that were going to feed these pipelines are now the casualties of huge spending cuts. Whether it’s Keystone XL, Northern Gateway or Energy East, none of the proposed pipeline projects has an economic context in today’s oil market.

The billions in cancelled investment are bad enough, as the last five months of GDP numbers attest. But there could be worse to come. Not only do new oil-sands projects no longer make economic sense, but even current production is no longer profitable. That may be news to the country’s politicians, but it’s certainly not news to investors who have been fleeing from the resource in droves. Hemorrhaging red ink, oil sands stocks are now trading lower than the bottoms reached during the Great Recession. The oversized weighting of the energy sector (roughly 20 per cent) has cast a pall over the performance of the entire TSX.

Instead of spurring ever-greater production, today’s oil prices signal a dire need for production cutbacks. And tomorrow’s prices can only amplify that message, as the ever-pressing need to limit emissions-driven climate change forces the world to combust less, not more, fossil fuels in the near future. The International Energy Agency estimates that if we are to avoid the worst consequences of climate change and hold atmospheric carbon to 450 parts per million, world oil consumption will have to fall by more than 12 million barrels a day over the next two decades, pointing to even lower oil prices in the future.

What type of future does that hold for the oil sands and Canada’s ambitions to become a leading world producer of oil? Instead of spending billions of dollars on developing new oil-sands mines, the industry, or more likely taxpayers, will have to spend billions of dollars on decommissioning oil-sands operations that are no longer economically viable.

Mr. Harper’s carbon-fuelled energy agenda hasn’t worked out, and that’s put the Canadian economy in precarious shape. But this critical moment of economic and environmental crisis is an opportunity for Canada to confront the reality, costs and urgency of climate change, and find solutions that will both reduce greenhouse-gas emissions and contribute to the economy. This is a challenge that every party in the current campaign should address.