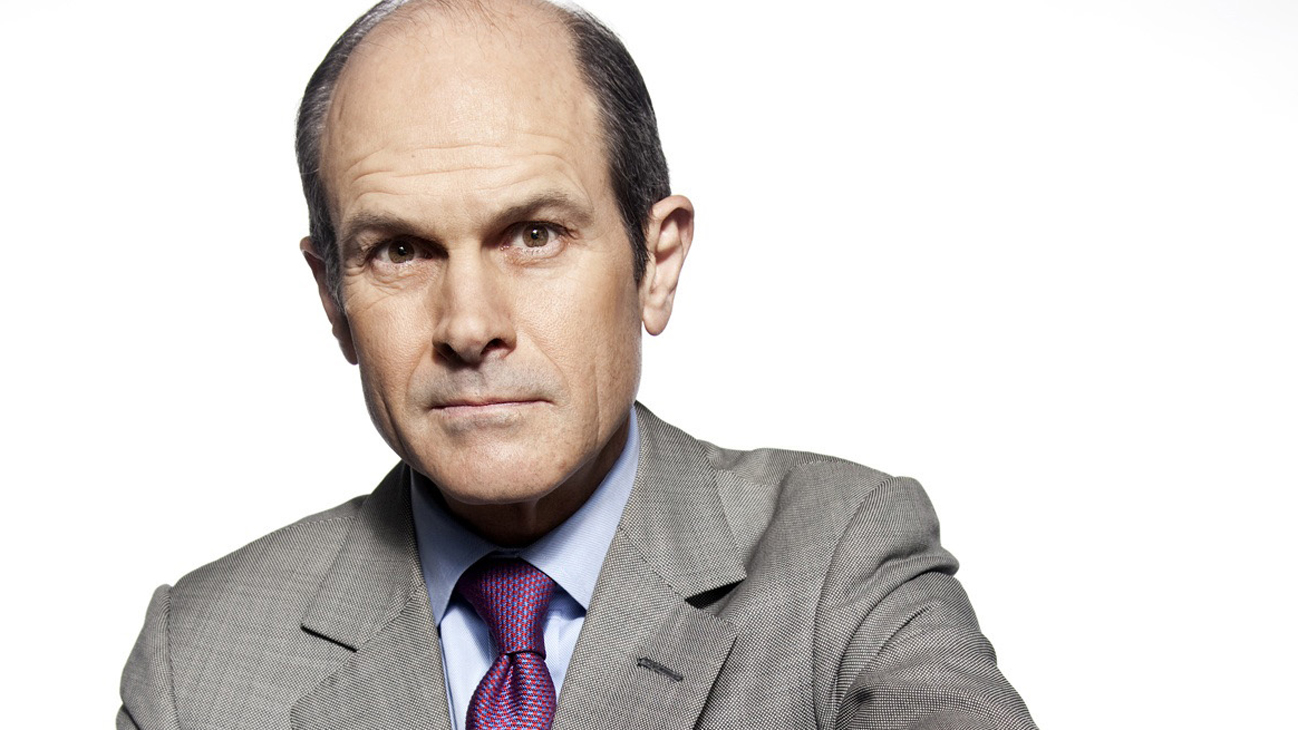

Millions of eyes and ears count on―and respect―Geoff Colvin’s insights on the key issues driving change in business, politics, and the economy. The senior editor of Fortune magazine, and named by Directorship magazine as one of the “100 Most Influential Figures in Corporate Governance,” Geoff draws on his years of insider access to top government figures and high-profile executives to share effective leadership strategies, and provides his unparalleled perspective on the business climate of today…and tomorrow. Geoff wrote the feature story for the latest issue of Fortune, for anyone who is interested in new ways to spur innovation, drive growth and improve organizational performance.

The one thing absolutely everyone knows about working at Google is that you get free, gourmet-quality food all day long. Stuffed quail, lavender pecan cornbread, aloo gobi, fresh fruits and vegetables, Gruyère mac and cheese—just go get it. Many know also that Google provides free gyms, free massages, and generous parental leave, plus cash bonuses when a baby is born; dogs are welcome. Beautiful offices are about to be upgraded in a spectacular planned new headquarters in Mountain View, Calif., the New York Times reported in late February (though details on the campus were sketchy at presstime). So when people see that Google GOOG -2.59% is No. 1 on Fortune’s new ranking of America’s Best Companies to Work For—for the sixth time—they understandably figure the reason must be those incredible employee perks. But that isn’t why. Knockout perks aren’t the reason any company makes this list. The essence of a great workplace is just that: an essence, an indispensable quality that determines its character.

Understanding that quality—understanding it well enough to build a corporate organization around it—has long been a goal of great companies. And it’s getting rapidly more valuable too. That’s because as the economy changes, employers who don’t know the secret will be at a deepening disadvantage to those who do.

Which brings us back to those famous Google perks. The truth is, while the most sought-after talent doesn’t generally flock to a company because of certain benefits and giveaways (nice as they may be), the perks themselves can teach us about the company’s essence—why, that is, some employers are such super-powerful magnets for the world’s best employees year after year. Listen to what an ex-Googler told Quora.com about Google’s nonstop free buffet: It “helps me build relationships with my colleagues.”

Hold on—food helps build relationships? It does when it’s used right. Data-obsessed Google measures the length of the cafeteria lines to make sure people have to wait a while (optimally three to four minutes) and have time to talk. It makes people sit at long tables, where they’re likelier to be next to or across from someone they don’t know, and it puts those tables a little too close together so you might hit someone when you push your chair back and thus meet someone new—the Google bump, employees call it. And now we begin to see the real reason Google offers all that fantastic free fare: to make sure workers will come to the cafeterias, where they’ll start and strengthen personal relationships.

That is, the food is just a tool for reaching a goal, and the goal is strong, numerous, rewarding personal relationships. Success obviously requires more than free food, but we’re glimpsing the explanation of workplace greatness. That same Googler said, “The best perk of working at Google is working at Google,” and the No. 1 reason he gave was the people: “We are surrounded by smart, driven people who provide the best environment for learning I’ve ever experienced.” (For more on the company’s people strategy, see “Google’s 10 Things to Transform Your Team and Your Workplace” in this issue.)

Here’s the simple secret of every great place to work: It’s personal—not perkonal. It’s relationship-based, not transaction-based. Astoundingly, many employers still don’t get that, though it was the central insight of Robert Levering and Milton Moskowitz when they assembled the first 100 Best list in the early 1980s. (For their insights into this year’s ranking, see their introduction to the list.) “The key to creating a great workplace,” they said, “was not a prescriptive set of employee benefits, programs, and practices, but the building of high-quality relationships in the workplace.” Reaching far deeper into people than corporate benefits and cool offices ever can, those relationships are why some workers love their employers and hate to leave and why job applicants will crawl over broken glass to work at those places.

In the past, of course, plenty of non-great places to work have managed to succeed without mastering this understanding. And many, no doubt, will continue to thrive. But all evidence suggests that this track is about to get much harder. Big, deep structural changes in the economy are likely to boost the advantages that great employers already enjoy in the marketplace and penalize even more the companies that fall behind.

It isn’t just because human capital is growing more valuable in every business. That trend has been going on for decades as ever fewer workers function as low-maintenance machines—turning a wrench in a factory, for example—and more become thinkers and creators. The remarkable thing is that while most trends eventually peter out, this one just keeps going. Intangible assets, mostly derived from human capital, have rocketed from 17% of the S&P 500’s market value in 1975 to 84% in 2015, says the advisory firm Ocean Tomo. Even a manufacturer like Stryker gets 70% of its value from intangibles; it makes replacement knees, hips, and other joints loaded with intellectual capital.

Companies will continue to gain a competitive advantage by attracting and keeping the most valuable workers, which is reason enough to become a great workplace. But interestingly, there’s a shift here as well—namely, in who is considered valuable. For decades—since Peter Drucker coined the term in the late 1950s—the MVPs were the so-called knowledge workers. But that term is no longer an apt description of the most prized personnel. The straightforward reason is that knowledge is becoming commoditized. Information, simple or complex, is instantly available online. Knowledge skills that must be learned—corporate finance, trigonometry, electrical engineering, coding—can be learned by anyone worldwide through online courses, many of them free. They can even be performed by a clever algorithm. Knowledge remains hugely important, but it’s gradually becoming less of a competitive advantage.

As technology takes over more of the fact-based, rules-based, left-brain skills—knowledge-worker skills—employees who excel at human relationships are emerging as the new “it” men and women. More and more major employers are recognizing that they need workers who are good at team building, collaboration, and cultural sensitivity, according to global forecasting firm Oxford Economics. Other research shows that the most effective teams are not those whose members boast the highest IQs, but rather those whose members are most sensitive to the thoughts and feelings of others. MIT professor Alex “Sandy” Pentland, a renowned data scientist who directs that institution’s Human Dynamics Laboratory, has aptly summed up the new reality: “It is not simply the brightest who have the best ideas; it is those who are best at harvesting them from others. It is not only the most determined who drive change; it is those who most fully engage with like-minded people. And it is not wealth or prestige that best motivates people; it is respect and help from peers.”

Yup, these are the new corporate MVPs.

Many companies will struggle with finding and luring these top workers—as well as employing them in ways that get the most out of their interpersonal skills. But the best companies to work for are, mostly, already there. Creating and building relationships is the essence of what they do. Consider SAS, the giant software firm that’s one of the few companies to appear on our 100 Best ranking every year since we started publishing it in 1998. The firm surveys employees annually on the state of their relationships: Are they getting open communication and respect from fellow employees? Are they being treated like human beings? Or look at another regular on the 100 Best, the Wegmans supermarket chain. Here’s a typical employee comment: “Co-workers really care about each other on both a professional and personal level.” The perks at these companies are pretty darn good. But it’s the employees themselves that make them great places to work.

You’ve realized by now that we’re talking about culture, the way people behave from moment to moment without being told. More employers are seeing the connection from culture and relationships to workplace greatness to business success. Deloitte’s latest annual survey of 3,300 executives in 106 countries found that, for the first time, top managers say culture is the most important issue they face, more important than leadership, workforce capability, performance management, or anything else. “Culture” was Merriam Webster’s 2014 word of the year. It’s everywhere. Yet as employers increasingly grasp its importance, they also realize they have no clue where to begin in creating the culture they need.

Let the 100 Best offer a few hints. They focus on four elements of culture that make the most difference:

Mission. These companies are pursuing a larger purpose, and company leaders make sure no one forgets it. Whole Foods is improving customers’ health and well-being; USAA is supporting members of the U.S. military and their families; REI is helping people enjoy the outdoors sustainably. When employees are all pursuing a mission they believe in, relationships get stronger.

Colleagues. Several of the 100 Best also appear on lists of companies where it’s hardest to get hired; 14 of them, including Twitter, St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, and the Container Store, attract more than 100 applicants for every job opening. Those companies can hire the cream of the crop, creating a self-reinforcing cycle; the best people want to go where the best people are.

Trust. We all know this: Show people that you consider them trustworthy, and they’ll generally prove you right. Many of the 100 Best let employees work whenever they want, and they work far more than if they were punching a clock. Riot Games, maker of League of Legends, even offers unlimited paid vacation; strong relationships prevent employees from abusing the policy.

Caring. Every company says it values employees. The 100 Best don’t say it; they show it. This is where some of those celebrated perks do count. Google, for example, offers an employee benefit it has never publicized: If an employee dies, his or her spouse receives half the employee’s salary for a decade. No words could send as clear a message. A true culture of caring goes beyond perks and includes daily behavior—see Leigh Gallagher’s story on Marriott in this issue.

And yes, in case you harbored doubts, the 100 Best really do outperform other companies as investments. Analysis of the publicly traded firms in the rankings from 1984 through 2009 by Wharton’s Alex Edmans found that a portfolio of 100 Best Companies exceeded its expected risk-adjusted return by 3.5% a year. That’s what Wall Street calls alpha, and 3.5% annually over 25 years is a stupendous performance. The puzzle is how it’s possible. Why don’t investors realize that great places to work are also great investments, and bid up the stock price as soon as Fortune’s annual list is published, eliminating the subsequent outperformance? Edmans exhaustively investigated several hypotheses and concluded that investors just don’t get it—they simply don’t understand that great workplaces work better.

A corollary is that most employers don’t get it either. Why do they let the 100 Best clean their clocks year after year, when the secret is no secret at all? The answer is a mystery. We know 100 companies that hope the others never figure it out.