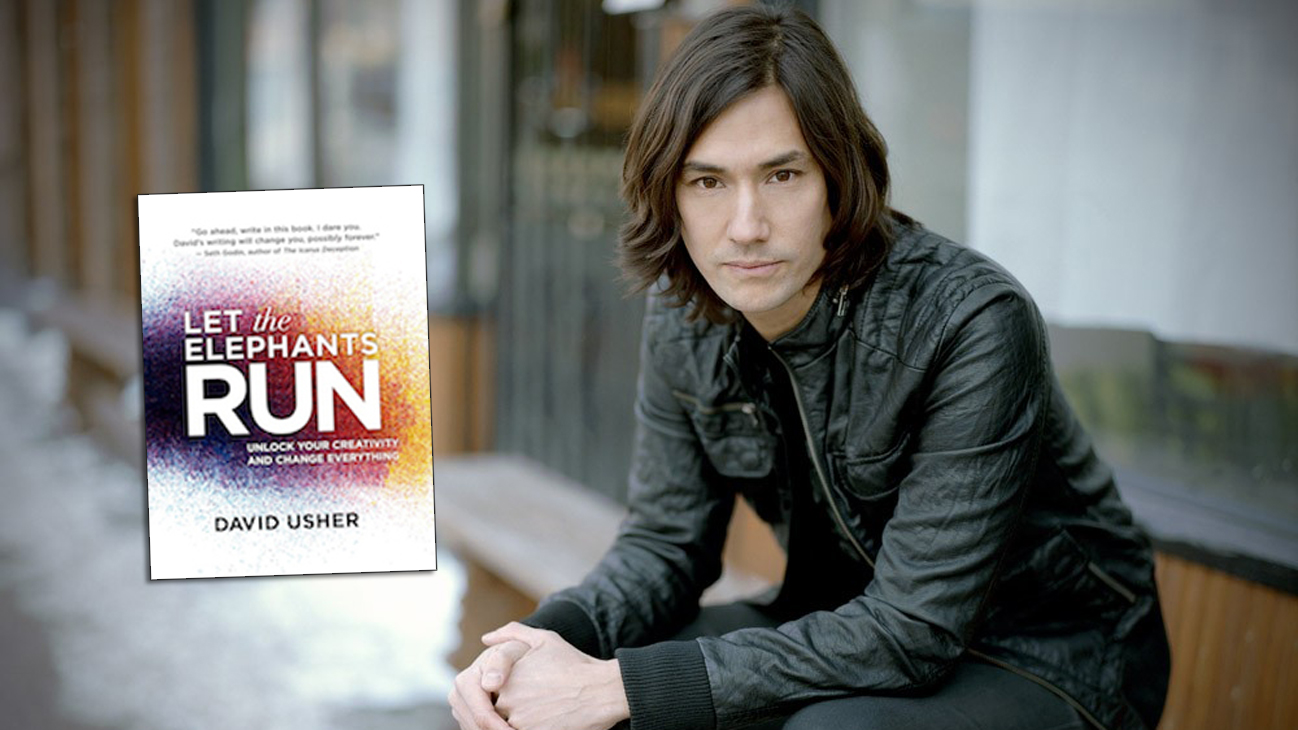

David Usher is a creative tour de force. As the front man of the internationally acclaimed rock band Moist, and as a solo artist, David has sold more than 1.4 million albums, won countless awards–including five Junos–and performed at sold-out venues around the world. Believing that creativity and creative success is a learnable skill that anyone can master, his unique and dynamic presentations employ music and video to show audiences the steps they can take to stimulate the creative process at home and at work. David has just released his new book, Let the Elephants Run, and The Montreal Gazette sat down with him to learn more. You can also watch their conversation here.

He looks younger than a 48-year-old has any right to. The hair might be a little shorter and bear the slightest hint of grey, but otherwise it’s as if David Usher has stepped right out of a vintage mid-’90s Moist video, several of which were branded onto the collective memory of a generation of Canadian rock fans via MuchMusic.

“There’s a mixture of things in there,” said Usher over coffee at La Croissanterie, up the street from his Mile End home. We’re talking about his unconventional family background and how it might inform the ideas in his new book Let the Elephants Run: Unlock Your Creativity and Change Everything (House of Anansi, 227 pp, $29.95), a kind of interactive exploration of how artists become artists, and how the creative process can be tapped and applied in other walks of life.

“My dad is a Montreal-born economist, a Jew from Westmount who literally grew up with Leonard Cohen. My mother is a Thai Buddhist from Bangkok. She’s a painter and he writes books, so there is that definite mix between freedom of imagination and intense structural process, which are the main two elements I’m dealing with in the book — the grand creative vision with the scientific underpinning.”

Usher’s memories of growing up in a peripatetic household involve “a lot of intense arguments around the dinner table about art and politics.” He did the unusual combo of a political science major and a dance minor at university before embarking on the rock and roll route with Moist in 1992. How, I wonder, did that choice go over with his parents?

“They were nervous about the shitty van we were riding around in, for sure,” recalled Usher. “And my dad thought that first video, for Push, was pretty weird. But at the same time they were very supportive. It helped, of course, that things blew up pretty quickly for Moist. It didn’t take long to start seeing the results.”

While books like Usher’s often stumble on the rather nebulous credentials of their authors, Usher’s credibility comes built-in: he has established parallel careers as a keynote speaker and creative consultant, but it’s as an artist who stayed prolific with solo albums even during Moist’s lengthy post-2001 hiatus (the band is now treading the boards again, with a series of Canadian festival appearances lined up this summer) that he commands the most attention, and the book is at its strongest when he draws directly on that experience. Presumably, as a still-active veteran of the CanRock renaissance, he gets approached by fledgling musicians seeking advice all the time?

“I do, and what I say is ‘Follow what you want to do, but be cognizant that a career in music doesn’t mean now what it did then.’ There’s a whole new set of skills you need. Back then the only way to do it was to get lucky with a big label. It was like a lottery. Now you can do it yourself, but the thing is, so can everyone else.”

If Let the Elephants Run has an underpinning thesis to its broad-ranging approach, it’s that, as Usher has already hinted, sooner or later you have to take your figurative mitts off and get down to the graft. Brainstorming over beers is all fine and good; it’s what comes next that really counts.

“Ideas don’t mean anything alone,” Usher said. “The reality is that it’s mostly work. Everyone has ideas, but who’s going to spend the time and do everything that it takes to determine whether that idea is actually good?”

If it’s sometimes hard to get that last point across, I suggest, it’s perhaps because the popular imagination has been skewed by the few outlier stories we always hear, of artists as open channels and receptors whose role is to pluck the great ideas fully formed out of the ether. It’s a romantic notion that Usher acknowledges but is keen to temper.

“Sure, Paul McCartney woke up with Yesterday fully formed in his head, but by that time he had already spent 15 years as a musician, desperately trying to write the best songs in the world, honing his craft in every waking hour, to get to that point. He had been collecting those ideas for a long time. Being there in the moment requires a mountain of groundwork and experience.”

Conversely, we’ve seen that as that cache of experience accumulates, there can come a point where maintaining creativity starts to get harder.

“That’s true,” said Usher. “You start to use up the easier metaphors, and find yourself having to reach farther and farther to find the connection points you haven’t used before. As a singer-songwriter you literally start to run out of words. That’s why it’s so great to be able to re-impose your creativity in other places. Suddenly there’s a whole wealth of virgin territory.”

Usher and his partner, photographer/theatre director Sabrina Reeves, have two kids, aged six and 12. Does he draw any direct connections between raising kids and being an artist?

“It really is about interactions and relationships,” he said. “Parents tend to interact with their kids in set patterns. We’ll have the same argument with them every morning about brushing their teeth and getting dressed. But sometimes we forget that, like the rest of the world, they’re in a state of constant change. They’re not the same people they were a month ago. They’ve moved on, so we need to inject something new into our pattern of communication with them.”

Finally, I relate to Usher how there are certain bands I’ve known personally, probably best left nameless here, for whom the creative process basically involved getting blasted, picking up a guitar, and seeing what happened. The mere idea of a book like Let the Elephants Run, I suggest, would probably have struck them as antithetical to their whole way of life.

“Maybe. But the thing is, there is a methodology, even if it looks haphazard and chaotic from the outside. Strip away all the drugs and the booze from the kind of scenario you’re talking about and there is still a process to what they were doing. Otherwise they wouldn’t have gotten anything done.”