How do you have your big purpose cut through all the noise and truly make an impact in the world? You can be bold, be ruthless, and be loud, but consultant and TED Speaker Nilofer Merchant found that the biggest splashes are reflective of one game-changing factor: Your support group.

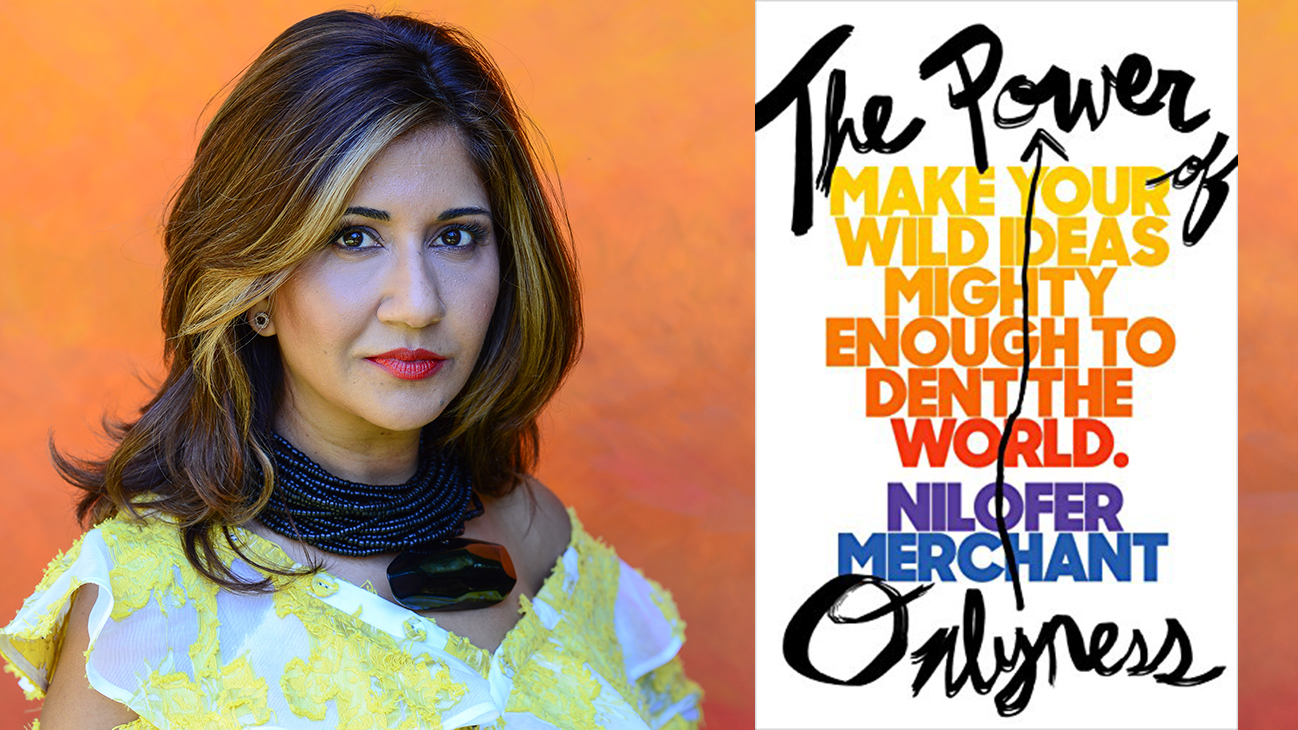

Merchant shares the serious formula in The Power of Onlyness: Make Your Wild Ideas Mighty Enough to Dent the World. I asked her about why your tribe outweighs your independence, the best way to create a strong network and how your vulnerability is your biggest strength.

Inc.: The book begins with your own personal family struggle and finding your own identity. It’s particularly vulnerable for a business book and adds a level of authenticity. What made you include it?

Merchant: It originally wasn’t going to be part of the narrative of the book! I was simply sharing other people’s stories – really going towards value-based ideas rather than the personal. But a friend of mine, formerly at CNN, read what would become Chapters 2 and 3, and she said jokingly, ‘Wow, I learned some much about these people, down to the color of their underwear. But I don’t know anything about you. Why?’ And she was right: I needed to tell my own story to give context to everyone else’s.

What do you want people to understand after reading the book?

There is a reason why we give up on our ideas, and it’s not because we don’t have courage or confidence. We cannot claim our own original ideas until we belong to a group of people where we feel safe enough to have those ideas.

I’m almost 50, and for years I’ve been going to conferences and told the same thing: Show more grit, have more confidence and be bold with your ideas. I’d do that the next day and it wouldn’t change anything! Until you have a group of people who can back you personally and give you a safe enough space to explore your ideas, you can never take the psychological risk to pursue your ideas.

We can find the people who care, who have our back, and it can change everything.

Not everyone has a brain trust. What would be the first step to building a network you trust?

As I mention in the book, Alex Hillman was a Philadelphian tech designer in his early twenties eating takeout along because he had no group – the techies he did know were all talk and nothing to show. He almost moved to Silicon Valley, but he realized he loved Philly and gave it one more shot. Unlike before, he began showing up at networking events not in suit, but in ironic t-shirts that showed his tattoos and a flannel jacket. He was himself. And he’d go to an event and find one person like him – since he was signaling, and no one can respond back until you do. Within four months he found five people who were equally geeky, and eventually started having beers and coding together, becoming much more productive individually.

The group got larger over time to the point where they would take over entire coffeeshops. They eventually decided to pitch in $50 a piece and rent an official space, which they named Indy Hall. It is now one of the major tech hubs in Philadelphia and inspired other groups to start, too.

If he didn’t do an intentional search, he wouldn’t have made it happen. You have to give yourself permission to seek out your people what idea you have in common and that changes your community.

If you asked him on day 1 or day 30, he wouldn’t even know where it was going, but he was chasing an idea into being. It is acknowledging something we see and, as we chase it, we get other people. But it isn’t a ripple until you actually start. We want more data, but most work can be done in an organic way.

You also emphasize that doing more of the same, just working harder, isn’t going to bring change. Why is it such an issue now? How can we avoid that trap?

I think it is the shift between the things machines can do well versus what people can do well. Machines are better at efficiency and repetition. I think of Henry Ford’s assembly line: We could measure people to do, say, 123 hood replacements, so the performance equals X and we can create accountability around X. It’s been more than 100 years since that measure of productivity was put into place, but we still believe that kind of productivity is the ultimate measure of accountability and, therefore, success.

Today, you can call it the social economy, the experience economy or the idea economy. All of us agree that it is about the ideas of people and how do you allow creativity to grow. As [100Kin10 founder Talia Milgrom-Elcott] told me, I’d rather fail at the right thing rather than succeed at the wrong thing. That is a human skill, for Talia being willing to be vulnerable enough, risk her success and sit with that uncertainty. This is our gift as human beings and not celebrating that gift would be a mistake.

One striking study in the book argues that you only need as little as 10 percent of a group’s support to create lasting change. How do we combat the entrepreneurial tendency to want everyone to love our big mission?

You start small, pull on that thread only you can see, find a group of people who feel it, too, and that will draw you to the next thing. Look at it like a repeatable, simple form of prototyping.

With entrepreneurs I work with, they’ll often say, “We want to raise $3 million”. I’ll often ask “So, what can you do with $50,000?”, and I’ll get a good idea of what you’re actually working on. We like to think big, telling stories about $4 million raises, but there is a whole set of stories about building steadily around the core audience.