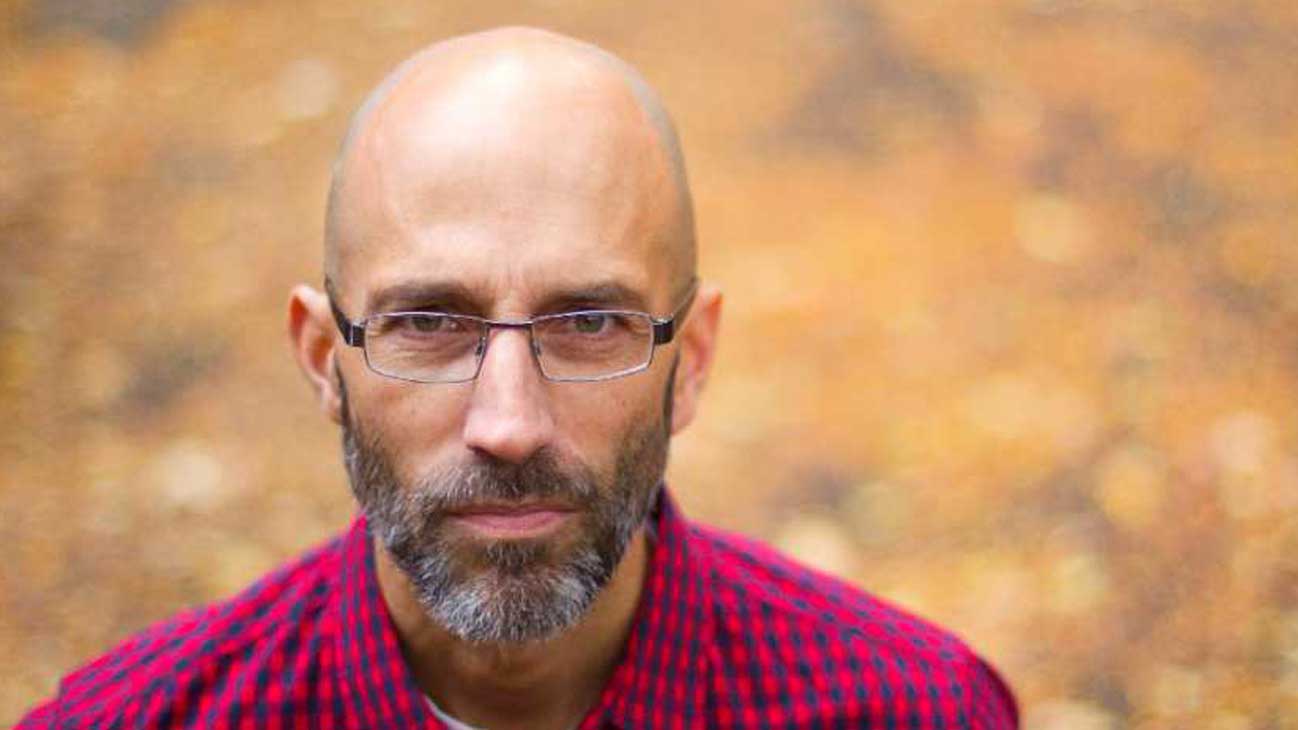

In today’s modern workplace, mental health problems have become the leading cause of disability claims, accounting for 70% of workplace disability management costs in Canada. As a former post-traumatic stress disorder sufferer, Lieutenant-Colonel (Retired) Stéphane Grenier knows the toll mental health issues can take on individuals firsthand. Stéphane offers audiences pragmatic advice designed to foster workplaces that support an open, non-stigmatized approach to mental health. In this article below, from 2014, journalist Charlie Fidelman from The Montreal Gazette recalls an interview she did with Stéphane that year:

Stéphane Grenier, a former soldier who suffers from post-traumatic stress syndrome, is a champion for improving mental health in the workplace, and not just for veterans.

Before he left the army in 2012 after 29 years of service, Grenier had already spent a decade developing peer support and education programs for the military. I spoke with the retired lieutenant-colonel, 49, when he was in Montreal in October for a lecture organized by AMI Quebec, which helps families manage the effects of mental illness.

Grenier was so enthusiastic about complementing traditional care with the power of human interaction that the interview stands out among the many that I conducted in 2014.

But how did Grenier get here? When I asked what led to his psychological war trauma, he said it started with Rwanda in 1994. It was bad, he said. Accepting what human beings can do to one another is transformational, he said. But no further details. Just something he called unrelated incidents that are common to war zones and peacekeeping missions.

We switched to talking about what drove him to complete one mission after another over the course of his career — Afghanistan, Cambodia, Kuwait and Haiti, to name a few. He said it was the addictive rush of adrenaline. Living in a danger zone triggers a switch akin to doing extreme sports. You feel really alive, he said.

But then, returning to civilian life between missions was an adrenaline crash. Boring, he said. Grenier had a hard time reintegrating into his non-military life with his wife, children and dog. No gun blasts or tanks rumbling at dawn. No genocide.

It was a disconnect. Let me tell you about one incident, he said, when he was having dinner at the house of his in-laws, who had recently come back from a week in Cuba. Grenier had just spent 10 months in Rwanda, yet the three-hour dinner conversation was all about the Cuban vacation. There were no questions about Rwanda, he said, in case the soldier would freak out.

The story Grenier wanted to tell at the table was one that no one could bear to hear.

“I don’t f—ing fit in any more,” he recalled when we spoke in October. “I have experience no one wants to hear about. It seems people are completely oblivious.”

Conversations with family and friends seemed futile, he said, since civilians can’t seem to relate to soldiers returning from war-torn areas who carry a combination of grief, stress, trauma and depression. He talked about being suicidal at one point during his recovery, of trying to work things out alone because he believed then that no one could understand what he was going through.

Grenier then made an eloquent and compassionate case against social isolation, a known risk factor for mental illness. His solution was to develop a national, certified peer-to-peer counselling program as a way of humanizing the workplace, where the stigma of mental health issues can be a barrier. Surprisingly, this turned out to be among the more positive of my interviews this year.

People don’t live in their doctors’ offices, Grenier said. What happens between medical appointments is crucial. It can tip the balance between life and death.