The past seven days have shaken a lot of people to their core. From the brutal aftermath that Hurricane Matthew has left in its wake, to the political maelstrom that’s erupted in the days since Donald Trump’s lewd comments about women in 2005 were let loose by The Washington Post and NBC, it feels as though there’s been a cloud of darkness hanging in the air. Whether the story was about the ineffectiveness of aid in getting to those who need it in Haiti, or about the (literally) millions of responses writer Kelly Oxford received to her Tweet in response to the Trump controversy (“Women: tweet me your first assaults”), the news the past week has been sad and heavy.

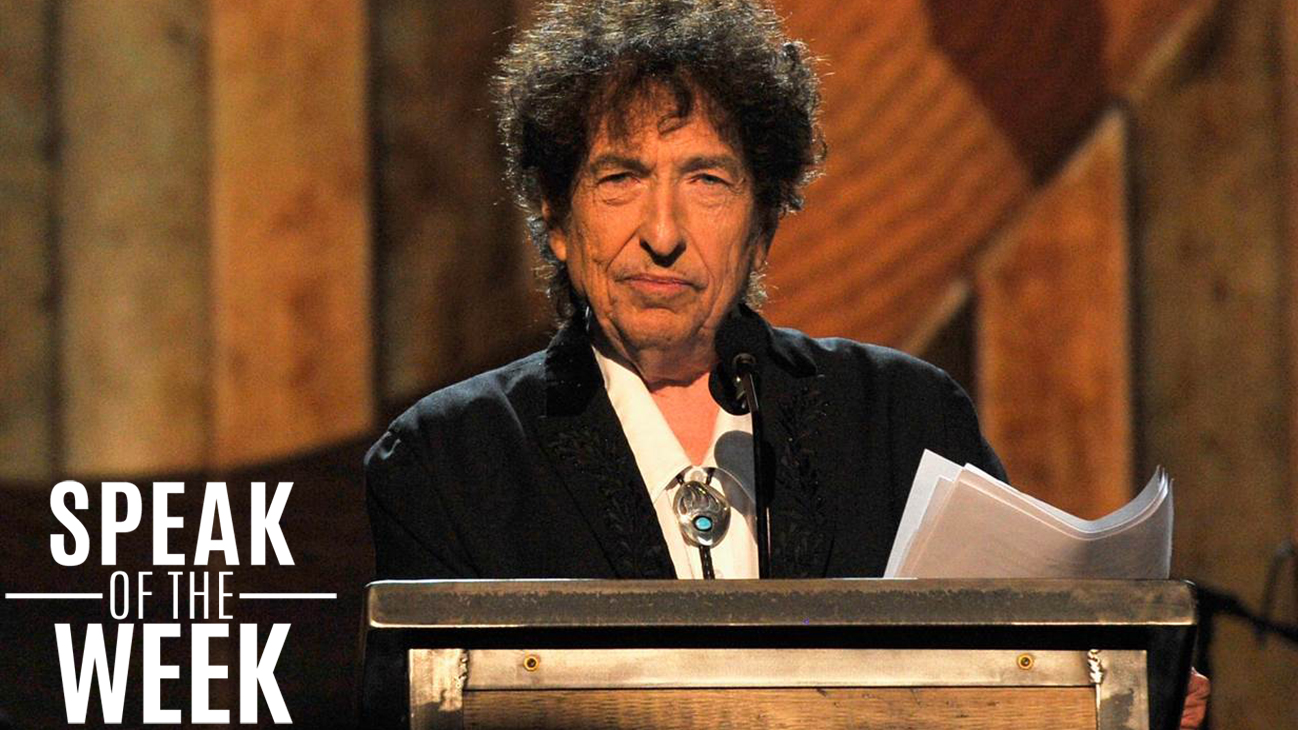

What a relief it was then, to wake up this morning to the heartening — and some would say, surprising — news that none other than Bob Dylan had won the Nobel Prize for Literature. While on its surface not an obvious match — the prize usually goes to someone who has written many books of fiction, and most had always surmised that the academy wouldn’t bestow its award to someone in the world of music – when considered, the surprise is not that Dylan won this year; it is that he hadn’t already won it before.

Dylan, whose career spans fifty-five years, is, as author Salman Rushdie wrote this morning, “the brilliant inheritor of the bardic tradition”, a lyric poet whose words demand to be sung, and by being sung have been shared around the world by millions, making him one of the most recognizable and popular musicians who’ve ever lived.

Cited by the Nobel committee for “having created new poetic expressions within the great American song tradition”, Dylan’s win in the category of literature raises the work that song writers have been doing since humankind first found our melodic voice to that of the great storytellers of history, echoing historian Otto Jespersen’s observation that “men sang out their feelings long before they were able to speak their thoughts.” The win cements the art form of popular music – from the folk song to the rock song – into the very bedrock of the other esteemed elements of our culture that the Nobel celebrates.

As all great writers do, Dylan’s music and musical career pushed the boundaries, whether he was criticising the establishment in his protest songs like Blowin’ in the Wind and The Times They Are A-Changin, or seemingly turning his back on the folk tradition he’d built his name on when he plugged in his guitar in 1965, and by pushing the boundaries, opened up a path for those that followed, from Jimi Hendrix to Lou Reed.

Whether acoustic or electric, one thing with Dylan has always remained true – his words have always been inseparable from his music. With lyrics that could have been written by the likes of Shakespeare or Philip Larkin — “Where preachers preach of evil fates / Teachers teach that knowledge waits”, from It’s Alright, Ma (I’m Only Bleeding) — whatever the words Dylan has put on an album or belted to a crowd stick in the mind of those that hear them, something to be rolled over and pondered long after the song itself has ended.

The most unorthodox Nobel literature prize winner to date, one assumes that when it comes to Bob Dylan, he wouldn’t have wanted this distinction to be any other way.

For bringing his words and wisdom to the millions of ears, hearts, and souls around the world for the past five and half decades, we choose Bob Dylan as our Speak of the Week.