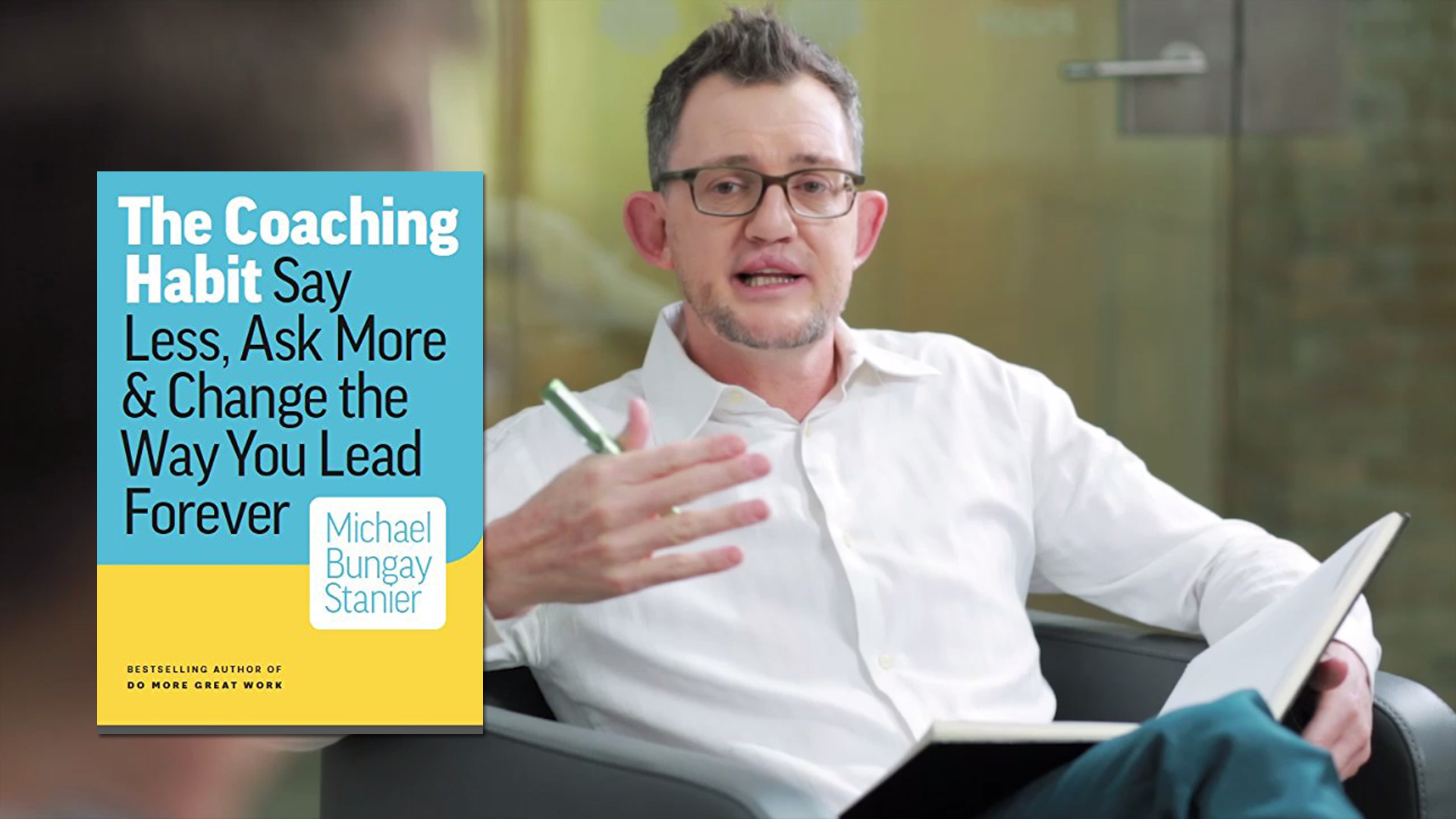

Your organization is set up to do Good Work–solid, reliant, efficient, work that delivers the next quarter’s numbers. That’s important. But it’s not enough. Michael Bungay Stanier knows that for organizations to continue to thrive and succeed, the people and teams in those organizations need to do more Great Work: the work that has impact, the work that has meaning, the work that makes a difference. In his new book, The Coaching Habit: Say Less, Ask More & Change The Way Your Lead Forever, Michael shows leaders how to make a difference in their employees’ lives through being a better mentor:

The more you know, the worse you’re likely to be at coaching your team. We figure that when subordinates come to us with problems, they are relying on our wisdom for guidance. And that leads to a habit which, according to consultant Michael Bungay Stanier, kills our ability to be an effective coach: You provide the answer you think they need rather than coaching them to find the path themselves.

“People have an inner advice monster – a deep need to give advice and offer recommendations that’s an instinctive response to questions,” the founder of Toronto-based consultancy Box of Crayons said in an interview.

Too often that prevents growth for subordinates. So you need to slay your inner monster, replacing the habit with curiosity. You want to explore possibilities with the protégé.

To learn this new habit, he offers seven questions to replace the urge to advise in his book The Coaching Habit:

1. What’s on your mind?

He calls this the kickstarter question, since it can initiate discussion in any conversation or meeting. Coaching these days has to be quick – it occurs in brief bursts – and this question brushes aside the normal chit-chat to focus on the heart of matters. It offers the protégé autonomy, but that can be a stumbling block to asking the question.

“If you’re in advice-giving mode, you feel in control. You have the status and feel you’re adding value. But when you ask a question, it leaves you in ambiguity. There’s uncertainty about where you may be headed. You are giving up power. You need the self-management skills to handle this,” he noted in the interview.

2. And what else?

This is his favourite question – “the best question in the world,” he insists – and it can be applied after any response you receive to a question. Rarely is the first answer the only or the best answer. But the tendency is to jump on it and give advice. So resist. Stay curious. Ask: “Is there anything else?”

3. What’s the real challenge here for you?

This ensures you have unearthed the real challenge. Too often we develop two options and pick the best, but research shows that is not as effective as selecting from even one more alternative. So get more possibilities out, and find the real challenge. How many choices do you need? “If you get five challenges on the table, people feel that’s lots of options to consider,” he said.

4. What do you want?

He calls this the foundation question, which transcends the previous challenge question to ask what is the outcome the individual you are coaching wants. The problem is you may resist asking that question, fearing the response will be something you can’t accede to. “You don’t have to say yes to every request,” he stresses. “You can say yes, no, maybe, or present a counteroffer. But if you ask the question or not, they want something. If you know what it is, you have some chance to act.”

Incidentally, a reason we resist offering feedback to others, he says, is that what we aren’t clear what we want. So ask this question of yourself.

5. How can I help?

After hearing what the challenge is or what they want, short circuit your instinct to act by asking the individual how they want you to act. Even a 60-second break before you offer advice will lead to a richer conversation.

6. If you are saying yes to this, what are you saying no to?

This instills a sense of strategy in your subordinate, picking between choices rather than jumping on the first opportunity or every opportunity. You can’t do everything, so get all the possibilities on the table explicitly before choosing. Often saying yes to something requires saying no to somebody else, so it’s important people become comfortable with narrowing choice.

7. What was the most useful for you?

This question is an excellent way to end meetings, encouraging people to reflect on what they are taking away. People don’t learn when you tell them something. It happens when they reflect.

Try seeding the questions into conversations – perhaps one question you’ll ask many times, because it’s a comfortable way to learn the habit, or planning different questions ahead of discussions. The hardest part is not choosing the right questions, he stresses, but getting to question mode and delaying the instinct to offer your brilliant advice.