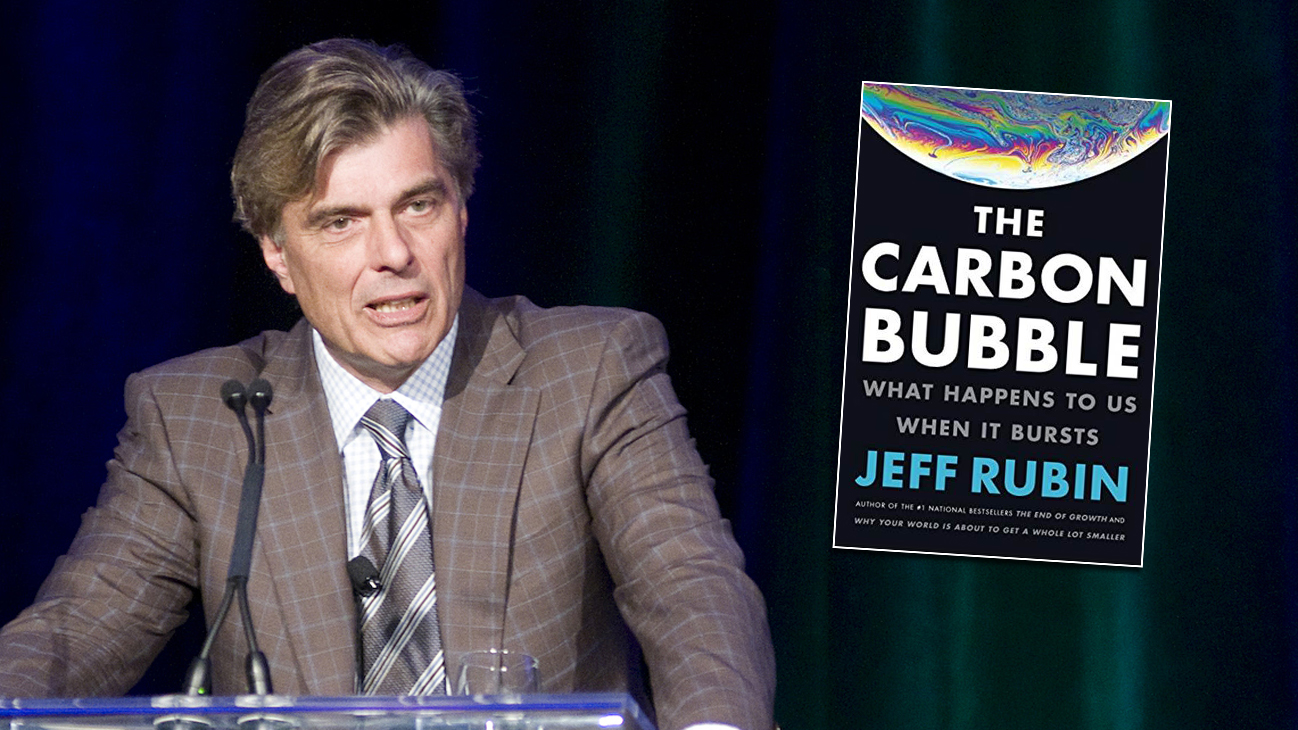

In The Carbon Bubble, Jeff Rubin explores how the very climate change that will leave much of the country’s carbon unburnable could at the same time make some of Canada’s other resource assets more valuable: our water and our land. Rubin was chief economist and chief strategist at CIBC World Markets where he worked for over 20 years. The Vancouver Sun sat down with Jeff to talk about his book and the many issues it touches on concerning oil:

Q: Tell us about your book.

A: I had two broad motivations for writing the book. The first was to explain to Canadians how their government’s chosen engine of economic growth, the massive development of Alberta’s oilsands, will fare in a world rapidly coming to grips with carbon emission driven climate change. Whereas the oilsands industry is planning for a massive expansion over the next two decades, the world’s scientific community is telling us that the global economy will have to dramatically reduce its combustion of carbon fuels if we are to avoid potentially catastrophic changes in our climate.

The second motivation for writing the book was to alert Canadians to the economic opportunities that climate change will bring. While rising levels of atmospheric carbon denude much of the value of the country’s high cost oil reserves, climate change will make other resources more valuable. None more so than the country’s arable land and its fresh water supply. In a time of climate change and ever-tightening restrictions on carbon emissions, Canada stands a much better chance of becoming an agricultural superpower than an energy one.

Q: How will Canadian farmers benefit from climate change?

A: The Canadian prairies have been identified by the U.S. space agency NASA as well as the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change as a climate change hot zone, where temperatures are expected to rise a multiple of the global average resulting in profound changes in both flora and fauna. Always a breadbasket, the constraint on prairie grain production has been the shortness of the growing season. That however is changing with a warmer climate and will change even more dramatically over the balance of the century.

The economic value of a changing climate on the Prairies is underscored by how climate change is adversely affecting other major food producing areas. That is already apparent in California, America’s largest food producing state, and is likely to become more apparent in the Midwest U.S. corn belt as well.

Q: What are your thoughts on a national carbon tax?

A: Just as the price of cigarettes does not depend on the cost of tobacco neither should the price of filling up at the pumps depended solely on the cost of extracting and processing hydrocarbons. We’ve got to start paying for the cost of carbon emissions every time we burn fossil fuels. But unlike tobacco, carbon is not some niche product in the economy. It’s pervasive. Putting a meaningful price on carbon emissions that incents us to emit less involves shifting the tax base from what we earn to what we burn.

Instead of today’s patchwork of different provincial regulations we need a national standard that applies across the country. B.C.’s $30-a-tonne carbon tax sets that standard. By making it more expensive to fill up at the pumps, gasoline consumption in the province has fallen in contrast to the rest of the country. At the same time the over $1 billion raised in annual revenue is offset by lower income taxes giving B.C. taxpayers more disposable income to spend on everything other than carbon fuels. That’s a win for the economy and the environment.

Q: What about B.C.’s LNG dreams?

A: Premier Clark’s government has its own energy super power dreams. Only they aren’t based on bitumen from oilsands but on LNG from fracked shale formations in the province’s interior. Unlike bitumen, which is the scourge of the environmental movement, natural gas is supposedly a much cleaner fuel and a bridge to an economic future.

At one point there were no less than 14 proposals for liquefaction plants and export terminals on the B.C. coast, all intended to serve the gas-starved markets of Asia. Today only the Petronas plan has any chance of proceeding and that’s a huge long shot at best.

As is so often the case in global energy markets, the goalposts have shifted. China’s lucrative natural gas market, the target of most proposed North American LNG terminals, has found cheaper sources of supply. Two blockbuster deals with Russia to supply the country with Siberian gas has undercut imported LNG prices by as much as 40 per cent and suddenly poured cold water on the mad rush to build LNG terminals both in B.C. and elsewhere.

And just as the economic goalposts have shifted against LNG, the environmental ones may soon move against shale gas. While conventional natural gas produces only half the carbon emissions per unit of energy than coal, those emission savings are highly suspect when the gas comes from fracked shale formations. Recent research, including studies from both Stanford and Harvard, indicate that fugitive methane emissions that occur with fracking are typically eight times higher than estimated by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Along with potential groundwater contamination and induced seismic activity, fracking remains a controversial form of energy extraction and is banned in many jurisdictions.