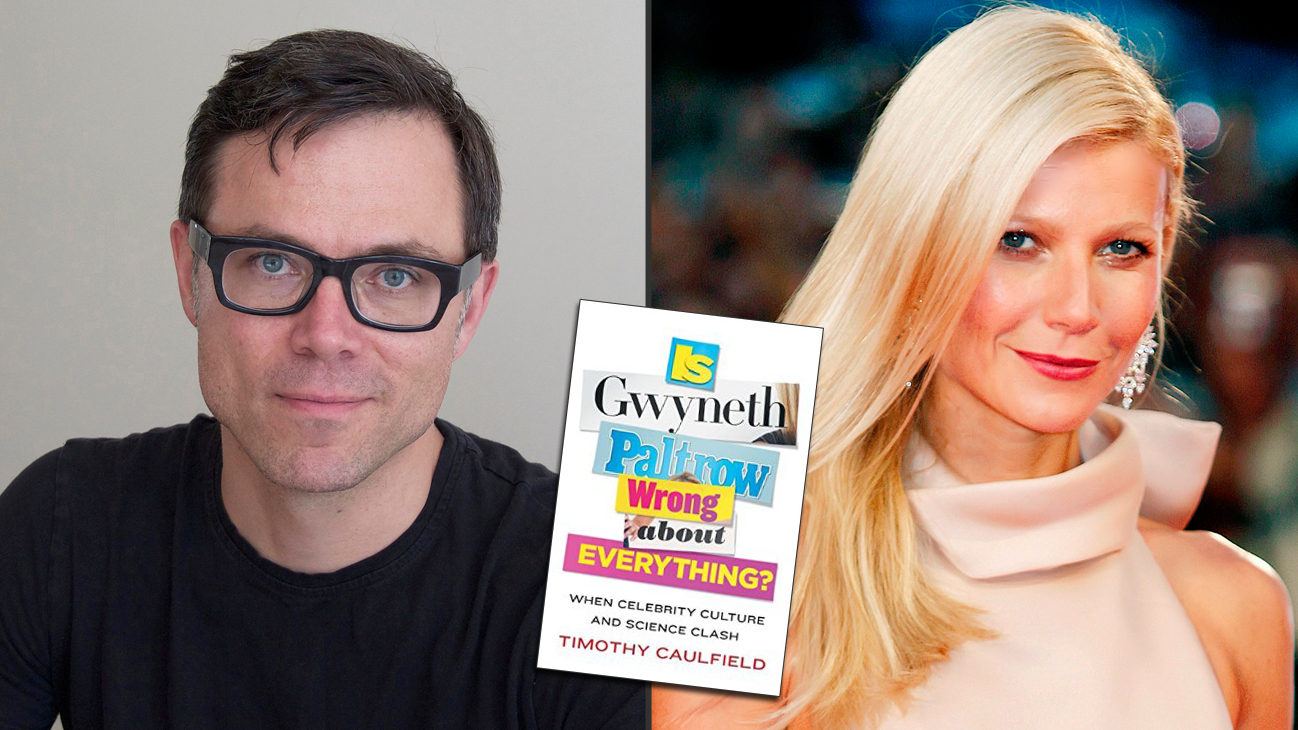

Over the past few decades, celebrity culture’s grip on our society has tightened. For Timothy Caulfield, a celebrated author and health science expert who is a University of Alberta professor and a Canada Research Chair in health law and policy, this culture has a measurable influence on individual life choices and health-care decisions. While acknowledging the pervasiveness of celebrity culture, Tim doesn’t mock those who enjoy it (in fact he loves celebrity culture), but with a skeptic’s eye and a scientific lens, he identifies and debunks the messages and promises that flow from the celebrity realm, whether they are about health, diet, beauty, or what is supposed to make us happy. The Telegraph spoke with him about his new book, Is Gwyneth Paltrow Wrong About Everything: When Celebrity Culture and Science Clash, below:

The undoubted poster girl of celebrity pseudo science, Gwyneth Paltrow has advocated everything from superhuman exercise routines to Mugwort intimate steaming, not to mention the Master Cleanses that left her “hallucinating after 10 days”. To her 2.1 million Twitter followers and 66,000 Goop devotees, there can be no better figurehead for the extraordinary pop culture phenomenon that is the power of celebrity authority over medical fact.

“I would love to sit down with Gwyneth, have some green tea – and talk science,” sighs Professor Timothy Caulfield, who last Tuesday found himself standing on a podium at Washington’s prestigious National Academy of Sciences, flanked by a large picture of the Hollywood star. “In the split second before I started speaking, all I could think was, ‘how did my career bring me to this moment?’” he chuckles.

The answer might have something to do with the award-winning University of Alberta-based academic’s decision to name his controversial new book Is Gwyneth Paltrow Wrong About Everything?

“The question mark was for the lawyers’ benefit,” quips the Canada Research Chair in Health Law and Policy. “And to be fair, it is a fine question.” A question Caulfield, 51, addresses methodically – and hilariously – in his systematic deconstruction of why celebrity “wisdom” often trumps science today when it comes to our health.

But the writer has tried in vain to get in touch with the 42-year-old star of Seven and Shakespeare In Love through her management and on Twitter. “Actually, I would just have one question for her,” he reflects. “’Do you really believe all this stuff?’”

He suspects that, to her credit, she probably does: “I do think she’s genuine. And I don’t think she’s wrong about absolutely everything. She probably eats good food and gets a lot of exercise, but even when she’s right, Gwyneth always manages to mix in a little bit of wrong,” he says.

The focus of his book, however, is not so much celebrities, “who are equally victims of this phenomenon, being under tremendous pressure themselves to stay thin or look young,” but a public who increasingly looks to them for answers on health matters. “Really it was individuals like Suzanne Somers and Jane Fonda who kicked all this off,” he says.

“But whereas in the past it was just a couple of people offering advice, more and more of them are now doing it. Whether it’s Katy Perry (who also propagated detoxes and cleanses) or someone like Shailene Woodley who just talks about health incidentally. Now, I’m sure Shailene doesn’t see this as a conscious part of her brand, but even if she doesn’t mean to advise people to eat clay for breakfast or sunbathe their vaginas, when people read about it on social media, that’s what they think they should be doing.”

Similarly, Caulfield points out, “the Jolie effect shows us what a complex phenomenon this is. Angelina Jolie was very thoughtful in the New York Times editorial explaining her decision to undergo a preventive double mastectomy. She didn’t make explicit recommendations; she only talked about her experience and her choices. But whereas some research said that the piece had a positive effect, other research found it may have increased anxiety around breast cancer in an unnecessary way. But you can’t blame or really get angry at any of these celebrities: it’s just the nature of pop culture.”

What you can do – and Caulfield has done to great effect in his book – is debunk all the health and beauty myths that have somehow acquired gravitas despite deserving nothing but derision. Ask him whether snail, placenta, human growth hormone or bee venom facials have anything to be said for them and he’ll machine gun back: “No, no, no and no. That was actually one of the biggest surprises when I was researching the book. I did think there would be some evidence to support these treatments but really there is nothing, aside from prescription strength stuff, that works. ‘Clinically proven,’ you’ve got to remember, means nothing at all.”

In the name of research, Caulfield also paid a visit to Gwyneth’s “cleanse specialist”, Dr Alejandro Junger M.D., and embarked on a cleanse that left him “in no doubt that Gwyneth is a tougher person” than he is. “The idea of detoxifying and cleansing is faulty on so many levels, it’s ludicrous,” he insists. “There is absolutely no scientific evidence to support it, and yet this very non-specific, amorphous concept seems to have an intuitive appeal: people really believe in it.”

Isn’t that down to a mixture of Puritanism and superstition? “Absolutely.” he agrees. “Cleansing has semi-religious connotations. It’s as though toxins have become Hollywood’s modern day evil spirits and we need to find a way to rid ourselves of those toxins. Because we’re blaming all our problems on them: our lack of energy, obesity and even bad moods. And it has just enough of a veneer of scientific legitimacy.”

That veneer is all the science people have time for these days, Caulfield believes. “The public has lost a lot of trust in science lately,” he explains, “to the extent that in the US people are talking about ‘The War on Science’. You see it at the GMO (genetically modified organisms) and vaccination debates.”

During his talks, Caulfield will often use a series of slides featuring conflicting headlines to explain why this has happened: “Bacon’s good for you”, “Bacon’s bad for you”; “Chocolate’s good for you”, “Chocolate’s bad for you.” “That kind of contradictory information causes people to shut science out,” he says. “And because science is a process and not an ideology or a list of facts, it makes room for celebrities like Gwyneth to tell people in a more palatable manner what they think. ‘Give me the truth,’ the public will say. ‘It’s the gluten, isn’t it?’ Or ‘it’s the toxins’.”

Our celebrity-soaked culture wouldn’t be quite so worrying if it didn’t goad people towards what Caulfield calls extrinsic goals. “It’s all about looking good in your bikini or for your wedding, as opposed to intrinsic goals: feeling good because you are eating well and exercising,” he says.

“And studies have proved that if you are doing things for extrinsic reasons, you are more likely to be dissatisfied with the result and you’re more likely to quit. Whereas if you do things for intrinsic reasons, you are more likely both to be satisfied and to maintain the healthy behaviour.”

A self-confessed “celebrity junkie”, Caulfield had wanted to embark on a celebrity purge of his own, “a really thorough cleanse”, he laughs, once the book was written. “But the truth is that people like Gwyneth do have a place in our lives as entertainers and artists,” he says. “Just as long as we don’t see them as being sources of truthful information on anything other than what they do.”

Meanwhile, if you need defiantly non-celebrity advice on how to live a long and healthy life, Caulfield has weeded out the guff and condensed it all down to a single sentence: “Don’t smoke, exercise – vigorously or occasionally – eat real food, watch your weight, wear a seat-belt, get a good night’s sleep and love somebody.”