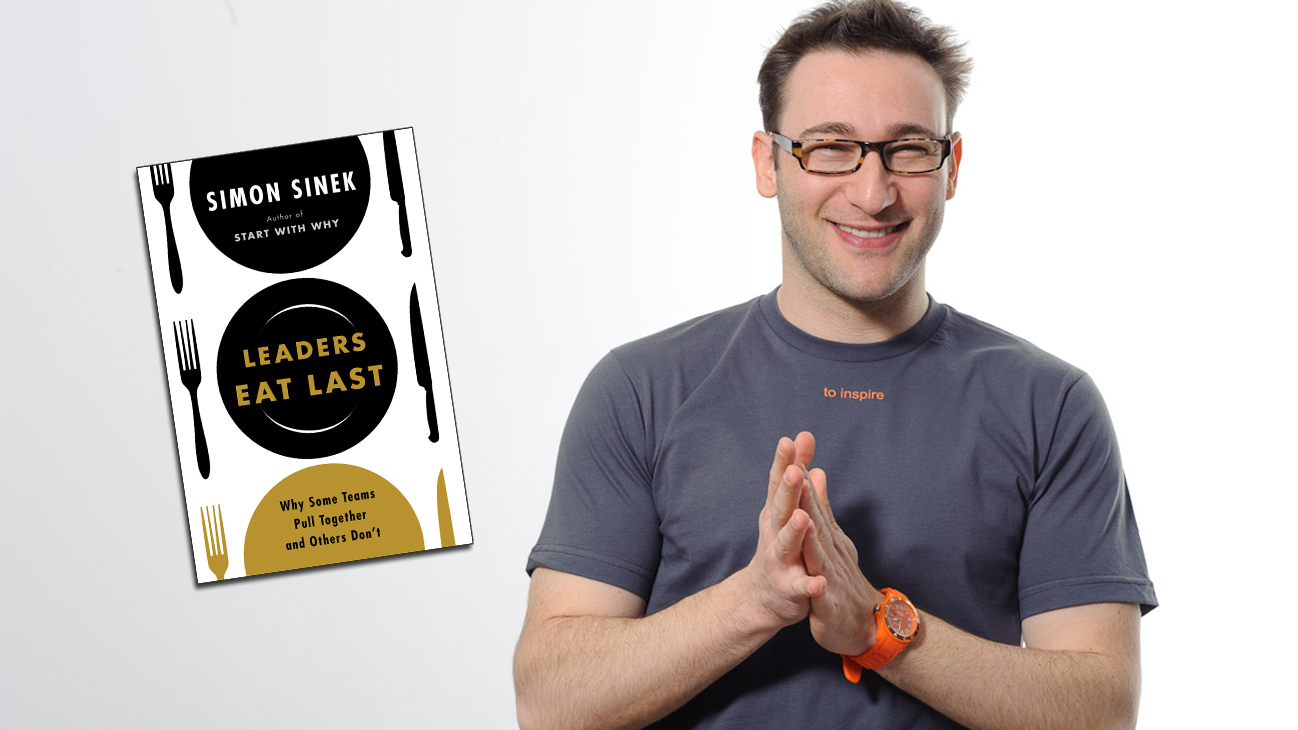

Renowned leadership expert Simon Sinek is leading a bold movement to inspire people to do the things that inspire them. The internationally bestselling author of Start With Why, he has just released his second book, Leaders Eat Last: Why Some Teams Pull Together and Others Don’t. The Wall Street Journal spoke with Simon about the premise of the book and why it’s important that leaders “eat last”:

If I’m an executive, why is it important for me to understand evolutionary history?

There are systems in our bodies that incentivize us to repeat behavior that’s in our best interest. So feelings of happiness, pride, status, joy, fulfilment, accomplishment—are all produced by chemicals inside our bodies.

When we create the right conditions for the way our bodies were built, we naturally cooperate and trust each other—and it feels really good when we do. However, the vast majority of corporate environments these days short-circuit our natural systems, and more likely promote paranoia, cynicism and self-interest.

If you’re capable of creating the right environment, not only do levels of trust and cooperation go up, but so does problem-solving, innovation and productivity; we work hard because we want to, and we help each other.

What can we do in the workplace to make colleagues feel safe and valued?

You can make someone feel safe by making them feel heard—by listening. When someone asks to speak to you, take your cell phone off the table and put it in a drawer. Close your laptop. Turn off your monitor.

Similarly, try using the phone—instead of email—to respond to someone’s ideas, or to deliver criticism or a compliment. Show your colleagues that you’re willing to give up time and convenience to interact with them. Even better, swing by their desk.

And if someone is underperforming, or is difficult, ask if they’re okay rather than criticizing.

But why do I have to eat last?

The concept comes from a practice in the United States Marine Corps, where officers eat last. To be a leader in the Marines, you have to make the decision to put the care of others ahead of yourself. So if you go to any Corps chow hall anywhere in the world, you will see that Marines line up in rank order, most junior first—and it’s not in any rulebook.

Is your book aimed primarily at executives, or are there ways that junior workers can make use of this mentality?

Let’s be very clear about what I mean when I say “leader.” A leader isn’t necessarily the person at the top of the organization—that’s the authority. There are plenty of people who run an organization who are not leaders. And there are plenty of people in the middle or lower levels of the organization who absolutely are leaders.

I think there’s a very clear anthropological definition of what a leader is: a person who’s willing to put the interests of others before their own. When you look at some of these early homo sapiens tribes, among the criteria that produced the alpha, or leader, was a commitment to the well-being of the group. When we feel safe amongst our own, we’re much more willing to commit our energy and our skills to the good of the group.

It’s exactly the same in the modern business world. When we fear our colleagues or don’t trust our authority figures, we have no choice but to redirect our time and energy towards protecting ourselves and our interests.

What does this type of leadership look like on a larger scale?

Leaders would sacrifice the numbers to save the people—and not vice versa. For example, Barry-Wehmiller Companies Inc. in St. Louis is a large global manufacturing company with about 7,400 employees. In 2008, when the economy hit the skids, they lost about 30% of their orders, and were considering layoffs.

But the CEO, Bob Chapman, absolutely refused. Instead, they implemented a furlough program. Every employee had to take four weeks of unpaid vacation whenever they wanted, and it didn’t have to be consecutive. Mr. Chapman said it was better that they should all suffer a little than some of them suffer a lot. And morale skyrocketed.

Did their numbers recover?

The company needed to save $10 million, and they saved $20 million—much better than they expected. The company continues to grow an average of 18% year-over-year as it has for the past 20 years. And it’s impossible to steal their employees.