Barbara Stegemann’s entrepreneurial vision was formed after her best friend—a soldier—was severely wounded in Afghanistan. Understanding that supporting Afghanistan’s economy was a key to building stability for its people, Barbara created The 7 Virtues Beauty—a company that sources organic oils from countries experiencing turmoil (such as Afghanistan, Haiti and the Middle East) to encourage change and to reverse the effects of war and poverty. Barbara has recently introduced her business to the UK market–The Daily Mail caught up with her for a thought-provoking chat:

Most women have a signature scent that expresses an aspect of their character. But imagine, if you can, a fragrance that conveys humanity, compassion, joy and every other fundamental emotion; love, hope and forgiveness, a deep longing for peace, an instinctive compulsion to reach out to those in need. Afghan Orange Blossom is just such a perfume. So too is Vetiver of Haiti; Middle East Peace (which combines grapefruit from Israel and lime from Iran) speaks for itself. These gorgeous scents are made from flower and other essences farmed on land where there is conflict or devastation.

The brand is The 7 Virtues and it’s a uniquely intriguing concept; the story of how they came to be made, by Canadian mother-of-two Barb Stegemann, 44, is no less extraordinary.

In 2006, Barb’s best friend Trevor Greene, a captain in the Canadian forces in Afghanistan,

was taking part in a peaceful discussion with village elders about how clean water and healthcare could be brought to the area. He had taken off his helmet as a gesture of goodwill, when a 16-year-old boy came up behind him and struck the back of his head with an axe. ‘It was horrific,’ says Barb. ‘Onlookers said his brains were falling out of the hole in his skull. Somehow he got emergency treatment and was flown to Germany, where his skull was rebuilt, and then transferred to Vancouver.’ The assailant had been killed by another member of the platoon.

After weeks in a coma, during which time Trevor’s fiancée was advised by doctors to ‘move on with her life’ (she didn’t, and they are now married), there were tiny signs of recovery; he woke up, then he could follow movements with his eyes, gradually he began to speak. All the while, Barb, who was running her own PR company just outside the city, visited him daily.

‘Trevor is a wonderful person, hugely philanthropic and conscious of a need to do good,’ says Barb, who had met him while at university in Halifax, Nova Scotia, where she studied sociology and he studied journalism. ‘Watching him try, over a two-hour period, to press a single key on a BlackBerry, I was humbled by his resilience and determination,’ she remembers.

‘I told him that I would carry on his mission in Afghanistan, in whatever way I could. I thought hard about how I could effect change and realised that I did have power; buying power. I knew that if I could harness the buying power of women, that could have a huge impact on poverty and education and the ability of communities to help themselves; all the things that are destroyed by war.’

Barb began researching Afghanistan online and came across two crucial pieces of information. The first was a story about essential-oils distiller Abdullah Arsala who was trying to support his tribe by creating legal crops of orange blossom and rose instead of the poppy crop that accounts for 90 per cent of the world’s heroin supply.

The second was research carried out by the Conservative MP and former diplomat Rory Stewart, who has experience in rebuilding post-conflict economies, having been stationed in Iraq after the coalition invasion. He later founded Turquoise Mountain, a non-governmental organisation in Afghanistan that aims to restore traditional industries.

‘Rory precisely calculated that if farmers were paid US $8,000 [£4,970] for a litre of orange-blossom oil and $10,000 [£6,200] for the same amount of rose oil, they will stop growing poppies; when people are given a choice they will choose the route that brings health and education to their children and stability to their community. So I decided that’s what I would do; I didn’t have a clue how to make a perfume, nor did I have financial backing, so I just called Abdullah and bought $2,000 [£1,240] of orange-blossom oil on my Visa card.’

It’s not the most conventional way of starting a business, but Barb is one of life’s self-starters. ‘I grew up in Nova Scotia, the most deprived region of the country, and even by those standards we were poorer than most,’ she admits. ‘My dad left when I was little and my mum brought up my older sister Marjorie and me, but we relied on social security to get by.

Mum wasn’t well, and would be hospitalised for long periods, but the neighbours would take us in and cook us meals.’ Both girls were bright – Marjorie is now a leading international virologist. ‘My mum used to say, ‘Marjorie is smart smart, but you, Barb, are people smart,’ smiles Barb. ‘And that’s probably true.’

After university Barb had a short-lived marriage, during which time her son Victor, now 18, was born. A single parent, Barb took a job as a flight attendant. ‘I would read the newspaper business pages every day and while I was pouring coffee I was quizzing the businessmen about markets and investments and storing all the information for when I would need it.’

After nine years, by which time she had a daughter, Ella, now 13, from another relationship, she left the airline and set up her own business communications company. She met and married her husband Mike Velemirovich, 49, who owns a car dealership. Then, when her dear friend was injured, her career abruptly took another path.

‘I bought orange-blossom and rose essences and brought them to a Canadian perfumier and together we created joyous fragrances. The first was Afghanistan Orange Blossom, followed by Noble Rose of Afghanistan – the “Noble” epithet is a tribute to the brave soldiers and farmers in the region,’ says Barb. ‘This isn’t a charity; I’m not giving handouts, but a hand up. It’s ethical business that appeals to ethical buyers.’ After two months and $30,000 (£21,000) worth of sales, Barb appeared on the Canadian equivalent of Dragons’ Den in 2010, offering 15 per cent of her business for $75,000 (£53,000) so she could buy more oils; before the cameras rolled, the show’s producers had already bought up the samples she had brought in. Three of the five dragons wanted to invest, and Barb – determined to keep learning – chose Canada’s equivalent of Sir Richard Branson, venture capitalist W Brett Wilson, as he offered not just money but mentoring. ‘Barb’s pitch in the Dragons’ Den was so emotional,’ he recalled. ‘It was empowering, captivating. You just can’t help but fall in love with the concept of doing trade with war-torn nations to lift others out of poverty and strife.

I had to jump on board this woman’s vision.’The following year, Barb launched Vetiver of Haiti, using oil distilled from plants grown on the island, and Middle East Peace, which blends Sweetie grapefruit oil from Israel with lime and basil oil from Iran. All profits go back into the business and Barb takes no salary; she earns her living giving motivational talks and from sales of her bestselling self-help book The 7 Virtues of a Philosopher Queen, which offers advice on how women can use their buying and voting power to tackle war and poverty.

The perfumes are best explored in The 7 Virtues Custom Blend Box, which offers tips on how to combine them; Noble Rose of Afghanistan with Vetiver of Haiti gives a masculine fragrance; Middle East Peace with Vetiver results in the aroma of ‘intense love’.

Barb has chosen not to visit Afghanistan; part of her ethos is to demonstrate that ethical trade can be conducted using new media.

‘I never go to these places as a business person because there are far more qualified people on

the ground; I let them get on with it.’

Her business model, which ensures that everyone in the chain – farmer, supplier, retailer, company – gets a fair price, saw Barb win the women’s innovator award for Canada, presented by the US State Department. The ceremony was hosted by Hillary Clinton, who was an instant convert to The 7 Virtues.

As a result, the Clinton Foundation then invited Barb to visit Haiti with the former president earlier this year. ‘I was the only Canadian invited, and one of the few small businesses. I met my suppliers and it was the most spiritual experience. I will never forget it’s the poorest place on earth.’

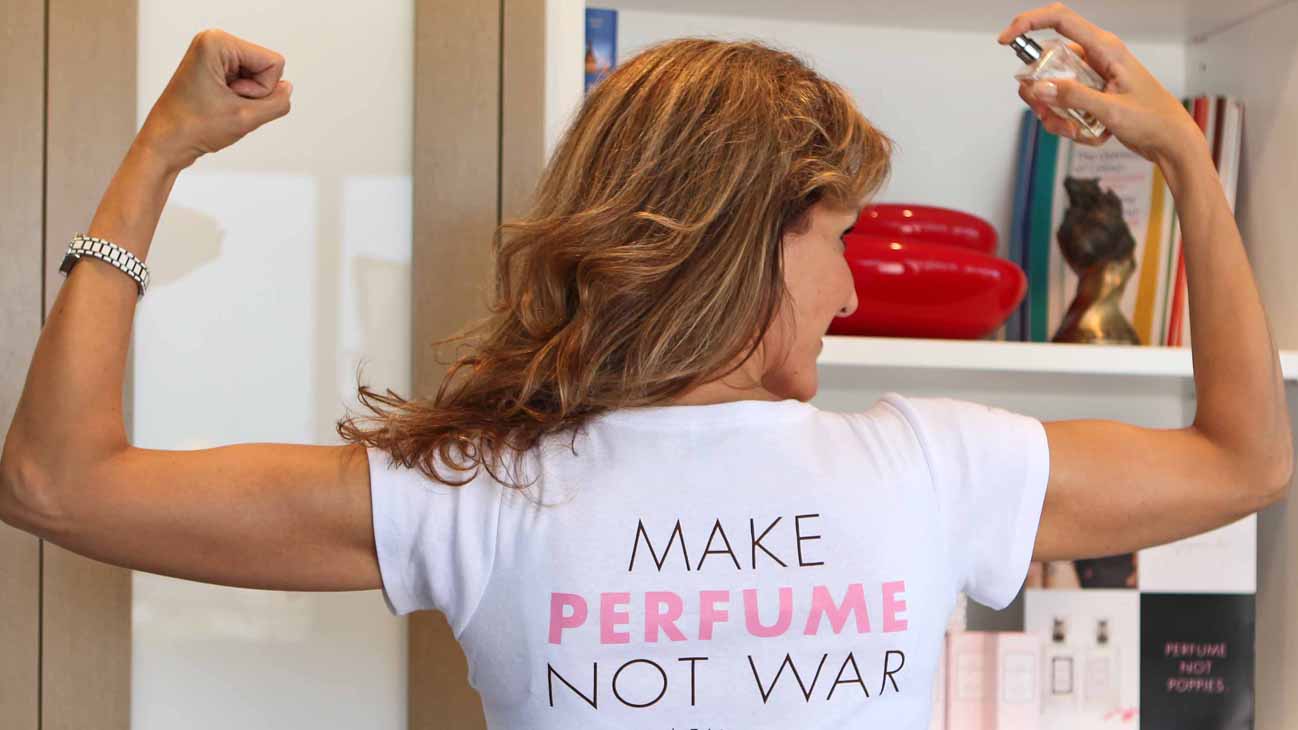

In the future she might add further fragrances using oils from Rwanda and North Korea. But

for now – and especially for Christmas – The 7 Virtues are available at Selfridges and online, under the tongue-in-cheek slogan ‘Make Perfume, Not War’. Customers, Barb hopes, won’t just

buy the fragrances, but buy into an idea of consciously seeking out goods from the

planet’s most benighted regions, thereby giving other entrepreneurs the impetus to follow her business model. ‘Buy their saffron, soap, candles, essential oils,’ Barb urges. ‘Buy anything that

will empower families to buy books and shoes for their children and take it to market.’

The distillery Barb works with in the Afghan city of Jalalabad employs 15 full-time staff and more than 1,500 seasonal workers. ‘I wanted to create the scent of happiness, not just of the wearer, but of the producers, the farmers, the factory workers,’ says Barb. ‘I don’t have a big-bucks advertising budget, but what I do have is people’s stories of how their lives have changed for the better and, of course, products that smell divine.’

And what of Captain Greene, who inspired this whole endeavour? Although he is still in a wheelchair, his mental faculties are fully restored and he and his wife have a 16-month-old son.

‘I think part of his healing process was knowing that something was being done,’ says Barb. ‘I’m not pretending to be the solution but I see the way forward, and the more businesses that join me, the more we can change the world.’ And, of course, share the sweet smell of success.

By Judith Woods/Daily Mail