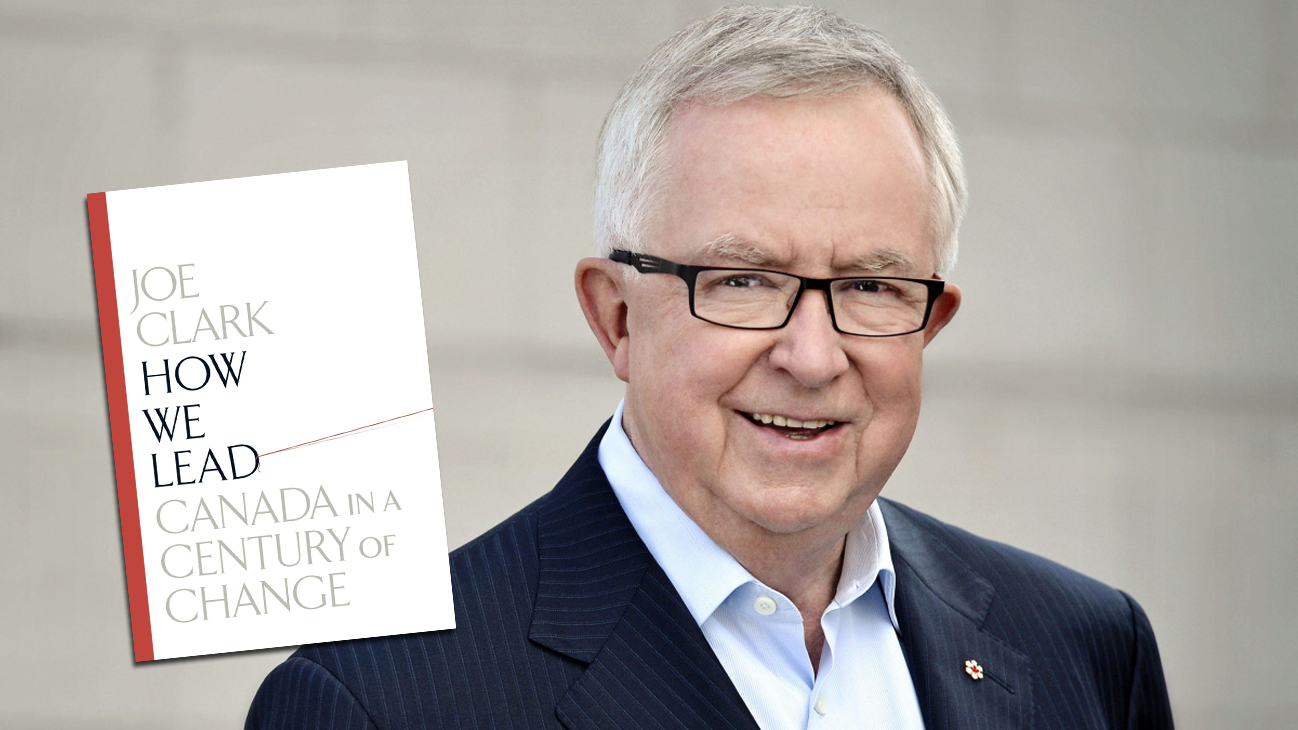

Canada’s 16th Prime Minister―The Right Honourable Joe Clark―is one of the most widely respected Canadians in history. A leader in fighting apartheid and promoting human rights, and the architect of significant Canadian initiatives in the Middle East, Asia, and Africa, Clark’s combination of integrity, commitment, experience, and fiery passion for the betterment of his nation is the foundation of all of his riveting presentations. The Globe and Mail sat down with Clark to discuss his new book, How We Lead: Canada in a Century of Change:

As if the Senate scandal wasn’t enough, when Prime Minister Stephen Harper gathers the Conservative Party faithful in Calgary this weekend, he may also have to deal with a broadside delivered by the longest-serving Tory foreign minister in Canadian history.

Joe Clark, who was minister from 1984 to 1991 (as well as prime minister for nine months in 1979-80), is releasing a book next week that is sharply critical of the Harper government’s foreign policy. He writes that Ottawa has squandered Canada’s reputation for bridging divides and has abandoned diplomacy by closing its embassy in Iran and boycotting the upcoming Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting in Sri Lanka over that country’s human-rights record.

Mr. Clark, who would likely note he was a Progressive Conservative, says former U.S. secretary of state Hillary Clinton’s description of her country’s approach to the Libyan civil war – “leading from behind” – demonstrated that even a superpower needs alliances.

Our country, Mr. Clark argues in How We Lead: Canada in a Century of Change, should “lead from beside.”

Your book has some sharp criticisms of Stephen Harper’s foreign policy. You say his government has broken with the past consensus. So what have they turned away from, in your view?

What they’ve turned away from is diplomacy as a principal instrument [of foreign relations] and international development as a major preoccupation. They are not much interested in either, and they’ve demonstrated that. Their emphasis has been insistently on the military, and latterly on trade – they came to that late, but they are pursuing it, I think, effectively. But there’s been a very sharp departure from the concepts of, you name any prime minister, really, since William Lyon Mackenzie King.

What do you think the cost has been?

Well, for one thing, almost anyone who works in international relations would argue that Canada’s influence has declined in the last six years, because we are seen as the country that lectures and leaves. Most recently in Sri Lanka, we are not there. We’ve pulled out of Iran at a time when a presence there is most important. We’ve alienated a very significant element of the international community in our hard line on environmental issues.

Canada is very much needed in an age defined increasingly by cultural conflict, and an age in which it is no longer possible for single nations to assume leadership to the degree that was the case before. There is a need for the concept of “leading from beside,” and no country has been better at that than Canada.

What do you mean by “lecturing and leaving”?

They’re not doing the diplomacy. They prefer the podium to the playing field. They see foreign policy as something you should talk about in terms that forcefully express your point of view.

To whom?

To anybody who will listen, to anybody who will stay in the room. But they are not sitting down and doing the hard work of trying to bring people together. I am talking about the people who are directing foreign policy – I’m talking about the Minister, the Prime Minister. What an odd time for us not to be at the Commonwealth conference. These are the places where, if agreement is to be found, it’s more likely to be found in a forum or a circumstance where people who normally disagree are inclined to have some common purpose, as is the case with the Commonwealth, the Francophonie, and others. Those are the areas where Canada made a great deal of difference over the last 50 years. And we’re just not going there anymore.

You talk about Canada squandering its soft power and its reputation as a bridge between “the West and the rest.” Why is that important?

It’s becoming increasingly clear that war-fighting, as we have traditionally known it, as we’ve been preparing to fight it, is not as effective in preventing conflict as it was thought to be. But the government continues to focus heavily on the defence side of the coin, and not at all on the development or diplomacy side, and that’s not going to address the growing issues of rising conflict. The reason that’s such a significant loss from the Canadian perspective is that, with all of our faults, we are one of the most successful societies in the world, probably the most successful in terms of managing and respecting difference.

You talk about not just country-to-country work, but teaming up with non-governmental organizations. Why is that?

I see this partnership as the future. NGOs have much greater freedom of action – they have that because they have bona fides, they are much more numerous, they attract much more enthusiasm on the part of their members. They are highly trusted in a world where traditional instruments are not. On the other side, the capacity of formal states to act is being increasingly constrained. As you’ll recall from the Libya experience, Hillary Clinton argued quite explicitly that there had to be a reliance on alliances to a much greater degree, even on the part of a superpower – a superpower towards which many people have suspicions. If that’s the case with a superpower, it’s certainly the case with a country like Canada.

I’d like the government to sit down with major NGOs and ask them, based on their experience, what changes there should be in foreign policy. I’d go back to the models that were struck when Lloyd Axworthy was foreign affairs minister. On both the land-mines treaty and the International Criminal Court, the government of Canada played maybe the leading role in bringing together partners who had similar interests but who had been in the practice of working apart.

You also suggest partnerships with countries that we have not worked with as closely in the past.

I’ve put forward a beginning list of counties that I think share some of the qualities that we have, and I would like to have Canada consider seriously how we might engage with those countries – with an Indonesia, with a South Korea, with a Turkey, with others. I think that would be a means not only of asserting our interests and our strengths, but also learning the possibilities of what other countries could do.

Some people have argued that Canada’s real interests lie in Washington, with allies. You argue Canadian soft power with “the rest” has value for allies.

I’m not arguing either-or. We had both before. We have reverted to countries like us, or countries that are very similar to us, so we are dropping an asset that we used to use, that we used to invest in, and we are doing that at precisely the time when that asset is becoming more valuable.

We were a natural strong partner of the U.S. because there were areas where we could do things that they couldn’t do, and a lot of those were in the developing world or the multilateral world. Well, now a lot of those countries to which the Americans needed a link and to which Canada sometimes provided a link are themselves growing economic powers, and as they grow they develop their own interests and the capacity to do things they couldn’t do before. We used to quarrel about whether the President, in his statements, was giving enough prominence to Canada. Are we really number one? Well, whether or not a president says it now, we’re in competition, strong competition, with all sorts of countries.

We were one of the countries of the G8 that also had very good relations with many of the non-aligned countries that are now emerging powers. We should be using those assets – not many people have them. And we have let those assets atrophy.