From the Toronto Star:

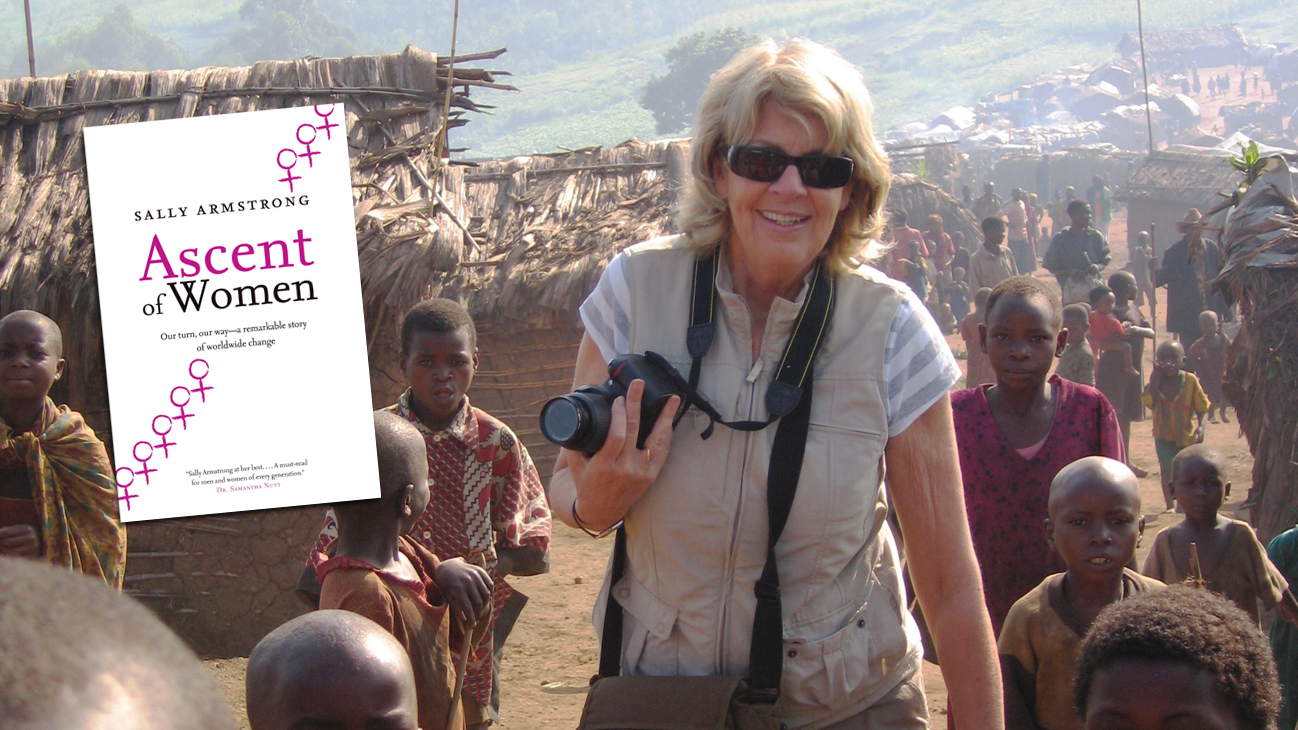

For a quarter century, humanitarian and journalist Sally Armstrong has been lifting the veil on the world’s disadvantaged women. From Afghanistan to Kenya to Congo, Armstrong has investigated searing stories which, she says, continue to play on the back of her eyelids. In her just-released Ascent of Women, the author argues that a tipping point in the oppression of women has at last arrived. What follows is an edited transcript of her conversation with the Star.

Q: “They attacked her like a pack of jackals. Six men stripped her, then raped her by turns, orally and vaginally.” This is an excerpt of your story of Eva Penavic, a Croat brutalized in the Balkan War, a story you told in Homemaker’s magazine in the summer of 1993. Who was Eva to you?

A: I was in Sarajevo when I heard about (the rape camps) and I thought it can’t be. This is before Congo. This is before Rwanda. And I asked around and I started hearing it from more and more credible people and at the end of the day I thought, there’s a story here. And I collected everything I could, everything, mobile numbers, anecdotes, names of doctors and survivors, and I brought it home to a news agency in Toronto and they didn’t use it. Twenty thousand women were gang raped. Six, eight times a day. Little kids. Old ladies. And I told my staff at Homemaker’s about it and they said, “Why don’t we do it? This is our story.”

I was interviewing a psychiatrist and he said, “I know a woman who wants to tell her story because she’s outraged.” And her feeling was if you don’t put a name on it and name the place it happened, you’re never going to change it. And that’s how I met Eva and that’s how I heard her story. She just wanted the world to know what had happened to her and how she had been so wronged and it just poured out of her.

Q: How can you explain the lack or rigour or tenacity that was evident in the Canadian media about bringing these stories home?

A: That’s really what my new book is about. Those stories somehow were seen as the lot of women. Soldiers rape women. That’s what happens. They pillage. Men get angry. Women get in the way. I think women’s stories were seen as the lot of the lives of women historically. I’ve been covering these stories for 25 years. A few years ago I started to get the impression that the earth was shifting and I did some research just based on whether that could possibly be true and discovered that it was and decided to write this book.

Q: The ’90s opened up for you a different world. Is that fair to say? You went to Afghanistan. You wrote first-hand accounts of the dark fate delivered to the women of Afghanistan by the Taliban. What is your current assessment of the plight of Afghan women?

A: I believe women are definitely the way forward for that whole country. But I think we have to understand it’s a very, very primitive place. And it’s not a place where people have enjoyed the conversations that we are very accustomed to in the West. And we all know that if you can’t talk about something you can’t change it. And Afghans I believe have only just found their voice. These young women told me that 67 per cent of the population of Afghanistan is under the age of 30. (Young Women for Change founder) Noorjahan Akbar, who’s in the book, said: “We never started a war, we never fought a war, we hate these old customs that hurt people. We want change and we have the tools to make change.” I feel there’s a good news chapter yet to write about this country.

Q: Just to cite one recent statistic, the UN reports a 20 per cent year-over-year increase in the number of women killed and injured, targeted by the Taliban.

A: We know these things, though. Stick your head up from under the earth and someone’s going to take a shot at you. To make change is sometimes dangerous. But I dare say we didn’t report these changes before. I don’t think we reported the deaths either. I think it comes back to the same story as the gang raping of women in the Balkans. It wasn’t seen as such a major story. I’m not saying I don’t believe those statistics. But let me give you an example. You may have heard the story of (child bride) Sahar Gul. When Sahar was locked in that little stone cell behind the house and being tortured, really tortured, her cries would have been ignored (as little as two years ago). There’s no way the neighbours would have reported it. Who would they have reported it to? Not only did the neighbours go to the police, but the police, who you know are notoriously corrupt in Afghanistan, they came to the house. This has never been done before. The Sahar Gul story was on the front page of papers around the world. That wouldn’t have happened before. I think we have to address the fact that something has changed, the earth has shifted.

Q: You went to Senegal in 1997 to report on the women of Malicounda Bambara who had pledged to eradicate female genital mutilation. How aware were the women of what was being done to them?

A: I would say the women of Malicounda Bambara were close to the first in this shifting earth. Because everyone tried to stop — they call it female genital cutting there — everyone tried to stop it. The League of Nations had people trying to stop this. Diplomats. Feminists. Everyone tried to stop it. But with these kinds of things no one can stop it except the people who are doing it. And these women were in health classes and the penny dropped when they realized that their hard-earned shillings from working in the field were being spent on ghastly health problems they had as adults because of what had been done to them as little girls. They said, “Who said this should be done? What do you mean this is our culture?” And until you ask you don’t know. And to their surprise when they asked nobody knew.

Q: The number of women who have been cut in Senegal has declined, but in Egypt, in Guinea, in Somalia the prevalence of female genital mutilation remains above 90 per cent for women aged 15 to 49. What does that tell you?

A: I thought it had started to drop in Egypt. I know Somalia’s is very high. Everybody in that business says it’s on its way out. It will end. And again it has to do with education. That’s the danger for fundamentalists and extremists and nut bars. If you educate your women they’re going to ask you why on earth you’re doing what you’re doing.

Q: You write that the world has reached a tipping point in the fight for emancipation, yet these are ugly times. As we speak an investigation has been launched into the rape and murder of three sisters aged 6, 9 and 11 from the Indian village of Lakhni. Police initially said the deaths were accidental. Rape is endemic in India and the numbers are rising. Where is the hope in that?

A: Well there is hope and my book is very hard on India. I spent time there with Indian women who are trying to make change. I refer you to (Jyoti Singh Pandey) who was raped to death and what that has caused, not only a huge increase in awareness, but it’s created a movement. For years and years, decades, I dare say centuries, we didn’t dare interfere in somebody else’s business and if you criticized the way somebody else behaved, either as an official or a family member, people would be quick to say to you you’re not from here, this isn’t your culture, it’s not your religion, it’s none of your business. Are we going to knock into that pride and say you’re not doing a very good job for your women? I am. I think a lot of people are saying it. Most important, their own women are saying it.

Q: The sadism is almost beyond comprehension. I’m thinking here of the brutal death of Anene Booysen in South Africa. They used it call it jackrolling. Gang rape for sport. The subsequent protest in South Africa was actually quite restrained, at least initially and certainly compared with the New Delhi gang rape of Jyoti Singh Pandey.

A: But who took these people on before? Who stood up and said what a monstrous act this is? Who named names? Rape carries such incredible shame with it because we’ve been taught to be ashamed and until very recently people didn’t attack it. There’s evidence almost weekly now that people are saying, “I don’t care what you think the culture is, I don’t care what you claim the religion says, this has to stop.”

Q: These jackrolling guys, they don’t even fear retribution.

A: I’m not sure of that. I remember a young girl in Afghanistan. She had been given in what they call “baad” at the age of 4. (Baad is the illegal tribal practice of giving a young girl in order to resolve a conflict.) She got away when she was 8. She was all covered in burns. I said to the man beside me when I met her, “How can you do that to a little kid?” And he said, “We know it’s wrong but it’s our way.” And I thought ah, you know it’s wrong. You know what? You just left a door open. You can work with people when they know it’s wrong. We haven’t paid enough attention to the vile behaviour of men in many places to convince them that (their behaviour) is unacceptable.

Q: Contrast your world view today to the world view you had when you set out on this journey.

A: I set out on the journey because I knew those stories weren’t being told. I don’t think I had any idea that it would become my life’s work, but it did. I believe that the stories I’ve been watching all these years have taken a very significant turn and it’s the women themselves who are rescuing each other. It’s not governments. It’s not UN policy. It’s the women themselves.

Q: As your book went to press, did you ask yourself whether you had been tough enough?

A: I think the book’s pretty tough. The book is layered with the horror. And it’s not as if the horror happened 10 years ago. It’s happening today. I agree my take on it is new. But I think I’m right, because I’ve been talking to these women for 25 years and what they’re telling me today is very different to what they said even five years ago. It’s a matter of, we have to take care of ourselves. Everybody else has promised they would but they never did.

By Jennifer Wells/Toronto Star/March 2, 2013