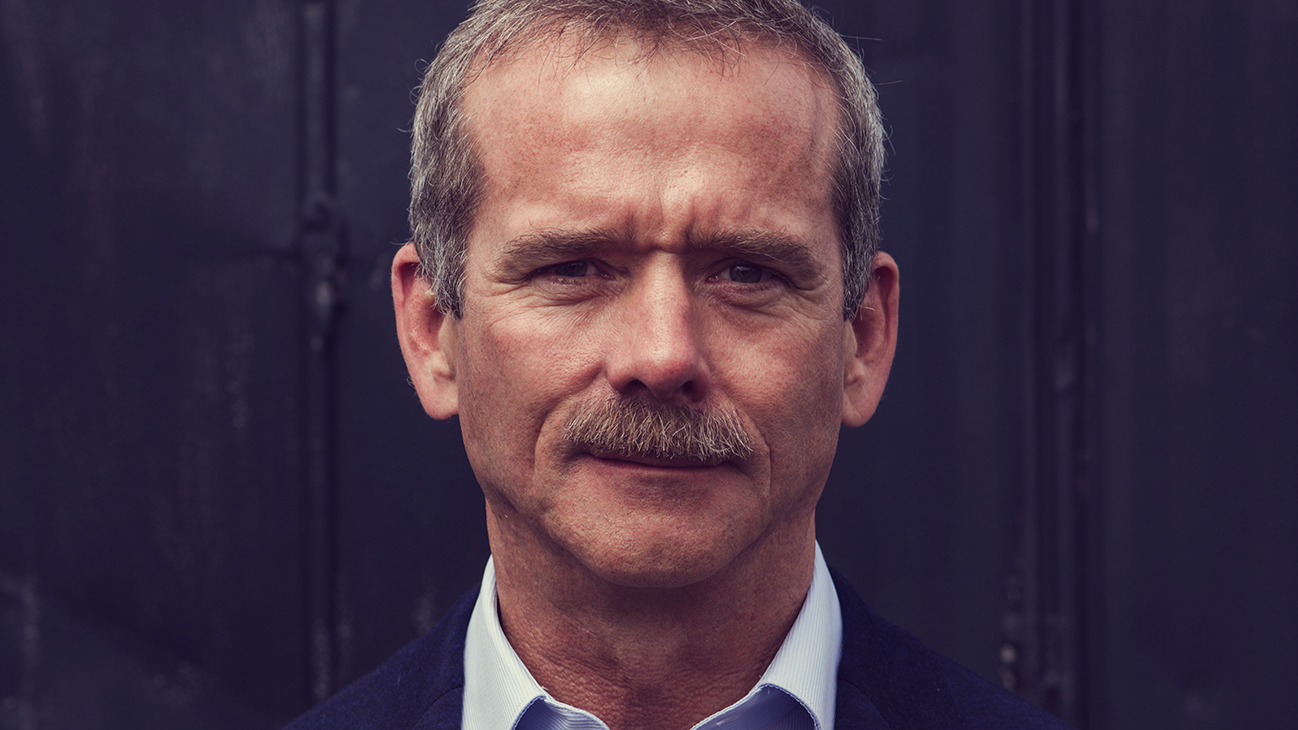

An astronaut and the founder of Creative Destruction Labs, an organization that drives research and innovation in the tech centre, it’s no wonder that Colonel Chris Hadfield accepted the position of co-chair and keynote speaker at this year’s Elevate festival — Canada’s leading tech and innovation event.

Chris spoke with Toronto Life on his role at this year’s festival, his passion for exploration and progress, and why he feels technology is the key to a sustainable future.

Toronto Life: Tell me a bit about your involvement with Elevate.

Chris Hadfield: I am fundamentally convinced by my own observations that the only way we can continue to succeed and improve our quality of life is through technology. It takes care of us all; it feeds so many people; it gives us so many things we take for granted. But in order to stay competitive and continue to challenge and enable our kids, we need to have good technology. We also need to provide future generations with opportunities to improve technology — to me, that’s what elevates all of us. So, when Razor Suleman [CEO and co-founder of Elevate] asked me to be a part of this festival, I was delighted to be one of the chairs.

TL: Your goal is to inspire people to learn about tech and get involved with it. How have people been resistant to that?

CH: It’s easy to just keep doing what you’re doing, right? Change is hard. The easiest way to see that is generationally. I look at my 85-year-old parents. We gave my mom an iPad two years ago, and she’s yet to turn it on on her own. And that’s normal enough. Everything that is invented until you turn 30 is cool and exciting, challenging and enabling. And everything that is invented after you turn 30 is stupid.

You have to recognize that this is the standard way people are, and also that the pace of invention is accelerating — especially improvements in communication and transportation. Consequently, you need to rethink your own assumptions and understandings of things.

My dad is a good counterpoint in that he was really against the whole idea of computers and the Internet and all that until he realized, “Wow, I can just push this button and everything is available to me. Oh, that’s really cool.” Now he’s a huge proponent of it. And, at 85, he has just taken advantage of the latest in solar conversion technology to equip his farm and cottage so that everything is 100 per cent powered by solar and small batteries. It’s improved his quality of life and decreased his impact on the environment.

I’m a big believer in the necessity of technology for quality of life. So, number one, you have to make technology possible. Then you have to make people aware of technology and convince them to adopt it. Often, you need something like Elevate to facilitate this introduction. You have to let an audience of people know about up-and-coming technologies and how we can use them to address some of our current technological shortcomings and make life better all around the world. I’m a believer in trying to replace whole generations of bad technology to let people leapfrog right into some of the great technology emerging right now.

TL: What are some of those bad technologies?

CH: Well, if you look at global studies on world health and birth rates, it looks like the Earth is going to peak at somewhere below 10 billion humans. If that’s the case — if by the end of the century there are 10 billion people on Earth — the world can easily support them. But it can’t support 10 billion people using the same technology we might have used if there were only 10 million people. We would use up all our resources or cause too much damage to the environment.

Think of the industrial revolution, for example, which used petroleum-based fuels harnessed through steam and later through internal combustion engines. These technologies enabled an incredible revolution in the quality of human life and a huge population explosion. And that was a wonderful thing. But when you apply that technology to 10 billion people, it won’t work. You cannot give 10 billion people the quality of life that people in Toronto have using the energy production, distribution and transportation technologies we’re using right now. That doesn’t mean that what exists is bad or that there’s no solution to it. We just need to continue improving and adapting to new tech, just like they did 250 years ago.

We tend to become very myopic in our own problems of today. We think that nobody in the past had problems as serious as ours, which is just an egotistical slant. Humanity’s problems have always been serious and existential and people have always found solutions, through their own resourcefulness, their ability to invent, work and share ideas. That’s no different than now.

TL: One of the challenges of our age seems to be a mistrust of facts and a rejection of science.

CH: Well, that’s no different either. It’s been that way forever. But the Internet provides what appears to be a level playing field for facts and opinion — so it’s deceptive.

In the 1780s, the very first human being rose from the earth in a balloon out of Paris. It was a huge event — the latest technology! Benjamin Franklin was there to see it and so were a couple of future U.S. presidents. It was a great scientific wonder of the day, to be able to fly using balloons. And yet, when the first balloon test vehicle crashed 15 miles from downtown Paris, the local peasants attacked it with pitchforks because they thought it was an alien descending from space. Only 15 miles away from the city, the lack of shared understanding of the advances of science was radically demonstrated. That was 250 years ago, and nothing has truly changed.

That said, we now have a rare opportunity to actually change things, because the vast majority of the world has incredible technology in their pockets — we can access the Library of Alexandria, global positioning, global communication. The resources of human knowledge that each of us has in our mobile phone is unprecedented.

It’s easy to focus on the noisemaking naysayers. You can believe in something in a breath. To actually understand it takes a little bit more work. Until you give someone enough information, they’ll just latch onto their own incorrect belief.

TL: What’s the balance, going forward, between publicly funded discovery and free enterprise?

CH: It’s a natural progression. Agile inventing and testing and a willingness to fail are very much the purview of private entrepreneurs like Elon Musk, Richard Branson, and, to some degree, Jeff Bezos. They are good influences.

If you’re the Canadian government, you have over 35 million shareholders, the majority of whom you have to please. That’s a very risk-averse organization. If you’re a private company like Boeing, SpaceX or Blue Origin, you can choose how much risk you want to adopt depending on how many shareholders you have. But if you are just one entrepreneur who has enough personal wealth to be the only real shareholder, you can be extremely risk-accepting. You can be confident in yourself. The question is, however, if you’re engaging in a dangerous business, are you willing to risk lives? You have to be, if you want to explore new technologies in transportation.

That’s where we are in space flight. The governments have invested in aviation since the Second World War. The technology became so good enough that it started to become commercially viable. That happened with aviation 100 years ago. Today, 11 million people a day get on a commercial airliner, and they go to a completely unlivable place, up at 40,000 feet. It’s 60 degrees below zero, and there’s almost no air. And yet they’re perfectly comfortable — and we’re shocked when it proves to not be 100 per cent safe.

We have this strange mentality where we want our technology to be so good that we can take it completely for granted. It’s wonderful that, to a large degree, we can. What’s happening in space right now is that governments have done all of the hard, unprofitable groundwork to build the bedrock of understanding on which everything else will be based. And now they’re turning to private enterprises who can start finding ways to make a profit.

You need people to be willing to change. You need to be excited by the fact that technology improves life on Earth and beyond. To me, such ideas are also both the draw and the purpose of Elevate.

Referred to as “the most famous astronaut since Neil Armstrong,” Colonel Chris Hadfield is a worldwide sensation whose video of David Bowie’s “Space Oddity” — seen by over 75 million people — was called “possibly the most poignant version of the song ever created”, by Bowie himself.

Acclaimed for making outer space accessible to millions, and for infusing a sense of wonder into our collective consciousness not felt since humanity first walked on the Moon, Chris continues to bring the marvels of science and space travel to everyone he encounters.

Interested in learning more about Chris and what he can bring to your next event? Email us at [email protected].