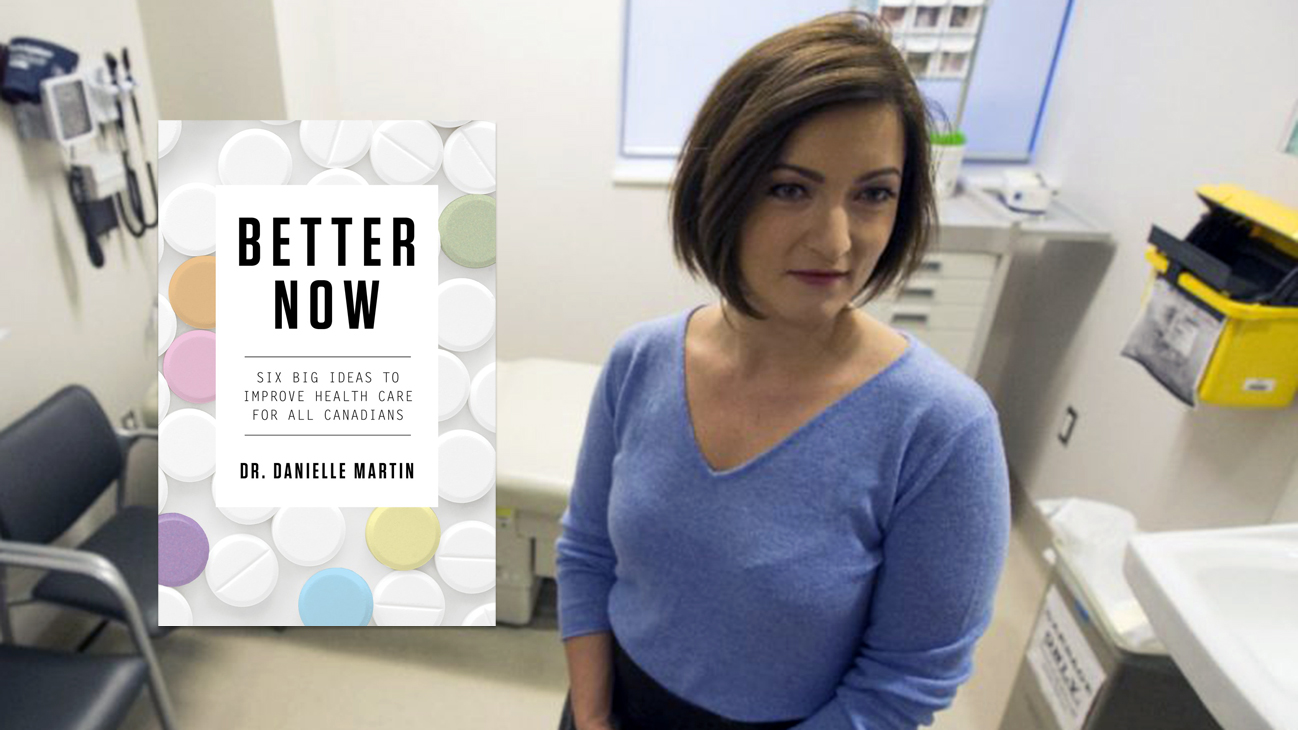

Dr. Danielle Martin sees the cracks and challenges in our health care system every day. A family doctor and national media commentator on the health issues that hit closest to home for Canadians, Dr. Martin speaks with passion on our national health-care system, defending and defining the ways we can make it even more worthy of our immense national pride. Dr. Martin has just released her new book, Better Now: Six Big Ideas to Improve Health Care for All Canadians, and the Toronto Star sat down with her to talk about it:

Her sense of social justice was nurtured during a privileged childhood, by parents who stressed the importance of giving back.

But Dr. Danielle Martin’s focus on protecting and improving this country’s universal health-care system can be traced to an earlier generation — to her grandfather, who died a broken man for want of it, before she was even born.

Martin’s stature as an eloquent advocate for Canadian medicare — which did not exist when her grandfather, Jacques Elie Shilton, had a heart attack in 1952 — has attracted invitations to join political parties of all stripes across Canada.

This wooing became particularly ardent following her appearance before a U.S. congressional committee in March 2014 — a bravura turn viewed 1.5 million times on YouTube.

Despite the political overtures and her agile oratory — honed as an undergrad debater at Montreal’s McGill University — elected office isn’t on Martin’s charts for the foreseeable future, the 41-year-old says.

“I don’t have political ambitions.”

Instead, she says, she’ll continue to concentrate on protecting and improving the country’s most valued asset — the health system she went to Washington to defend.

“Ninety-two or 94 per cent of Canadians will say medicare is a source of personal pride … an expression of what it means to be a Canadian,” says Martin, a founder and past chair of Canadian Doctors for Medicare.

Outside politics, Martin says, she can express herself unhindered by partisan stances.

“I have come to a point in my own thinking where I believe I can have a greater impact on health policy by avoiding partisan electoral politics, and instead continuing to engage in non-partisan work and public advocacy.”

A new book, Better Now, is Martin’s latest salvo.

To be released Jan. 10 by Allen Lane, a division of Penguin Random House Canada, the book is subtitled Six Big Ideas to Improve Health Care for all Canadians. And the author is no Pollyanna about the country’s medicare apparatus.

Martin sees a troubling disconnect between the pride Canadians feel in the provision of universal health care and their frustrations with its delivery.

“Too often people who believe in the principles of the public health-care system end up backed into this corner of being apologists for every single thing” about it, she says.

“And I can’t in good conscience as a physician working in that system defend everything about it.”

Martin says Canadians criticizing any aspect of health care are often labelled as traitors to the entire sacrosanct system.

“But the question is ‘that’s what we did yesterday, what are we going to do today to make it better?’ ”

Martin says her spirited activism was instilled by her mother, Anita Shilton, a dean at Ryerson University, and her father, D’Arcy Martin, a labour activist.

“I grew up being taught and therefore believing that everyone should be pitching in and doing what they can to make the world a better place,” she says. “There’s no way to say that that doesn’t sound cheesy, but it’s true.”

She also grew up with a tragic story about the desolate health-care landscape that awaited her maternal grandfather when he arrived here from an erupting Egypt in 1951.

In the book’s prologue, she recounts how Jacques Elie Shilton, a Renaissance man who spoke seven languages, was physically and financially ruined after his 1952 coronary. Breathing difficulties and crippling circulatory troubles followed. But in the pay-out-of-pocket medical system of the day, he often had to forgo needed drugs and treatments.

Chronic health and financial troubles caused his marriage to dissolve, and his need to borrow money for surgery strained broader family relations for generations.

“My mother found him dead at four o’clock in the morning on March 9, 1966 … he was 54 years old,” Martin writes. “My mother’s view is that the struggle to deal with the financial hardships — along with health problems — destroyed her family.”

Her grandfather’s story gave Martin the health-care focus that’s guided her career — a career that reversed the path taken by most activist physicians.

“For most physician leaders and physicians who are more active in system-level issues, the normal trajectory is that you begin” as a doctor, she says. “And (as a doctor) you come to understand and appreciate the importance of high-functioning systems and the social determinants of health and all of those larger issues as a result of one-to-one (patient) interactions.”

Martin, instead, dove head first into those big-policy issues after earning a science degree from McGill in 1998, becoming an assistant to Liberal health critic Gerard Kennedy in the Ontario legislature.

“I was passionate about improving the health-care system before I turned to medicine as a career,” she says.

Martin’s interest in larger issues almost cost her a spot at the University of Western Ontario medical school, where she earned her MD in 2003.

“I was sure I’d messed up my (admissions interview) because I went on a bit of a tirade about some systems issues,” she says. “I don’t even remember what they were anymore.”

Martin, who is vice-president of medical affairs and health system solutions at Women’s College Hospital, also earned a master’s in public policy from the University of Toronto, where she is now an assistant professor in family and community medicine.

After becoming a family physician in 2005, she practised on and off for six years in underserviced areas of northern Ontario. And Martin still combines her advocacy with an active family practice at Women’s College. That practice has earned commendation from colleagues and patients.

“She’s a fabulous, fabulous doctor,” says Meg Luxton, a patient of eight years. “She pays attention, she knows how to listen,” says Luxton, a professor in York University’s School of Gender, Sexuality and Women’s Studies.

Luxton, who has had four bouts with cancer, says she knew she’d found the right doctor at her initial appointment with Martin

“Just about the first question she asked me was ‘Tell me a little bit about your personal life,’ ” Luxton recalls. “She said ‘what do I need to know about you in order to have an understanding of your health context?’ No doctor had ever asked me that before.”

Dr. Danyaal Raza, a staff physician at St. Michael’s Hospital, says Martin’s advocacy has inspired many young doctors across the country.

“Danielle is an exemplar for many of us who are trying to integrate (health care) advocacy into our own careers,” says Raza, an assistant professor at U of T and a board member of Canadian Doctors for Medicare.

“She is a well-respected and national voice on health-care reform,” he says, citing her frequent appearances on CBC and regular column for Chatelaine.

Martin says her clinical practice has also put flesh, bones and faces on the medical policy issues she champions, and “connected my brain to my heart.”

Martin’s star congressional turn in 2014 came during a committee session concerning the U.S. Affordable Care Act, a.k.a. Obamacare.

Invited to share her views to the Senate health committee as chair of Canadian Doctors for Medicare, Martin calmly defended universal care before a powerful group of politicians who were often and disdainfully dismissive of the concept. Her performance was praised in the media, and by U.S. Senator Bernie Sanders, the committee’s chair.

(Asked sneeringly by one Republican senator if she knew how many Canadians died annually waiting for care under this country’s single-payer insurance system, Martin gave the withering response: “I don’t sir, but I know there are 45,000 in America who die waiting because they don’t have insurance at all.”)

Today, Martin says the U.S. president-elect’s vow to dismantle Obamacare will not threaten Canada’s health system nearly as much as his potential trade decisions.

“The thing that has the biggest implications on the Canadian health-care system actually isn’t so much what Donald Trump does or doesn’t do with respect to Obamacare,” she says. “It’s what happens with NAFTA.”

She says that agreement has provisions built in that protect Canadian medicare from U.S. free-trade challenges.

Martin lives in Toronto’s west end with her partner Steven Barrett, a prominent labour lawyer with Toronto’s Goldblatt Partners LLP. She says they lead fairly low-key lives outside their flashy professional careers.

“I have a 7-year-old daughter (Isa) who’s obsessed with Harry Potter,” she says. “And I’m a cook, (so there’s) lots of food and wine consumed in my household.”

Thus Martin laughs at the “power couple” label that many have ascribed to the pair.

“Ha! It does not resonate!” she wrote in an email.

“But I asked Steven and he wants to know if there is an application we can submit somewhere.”