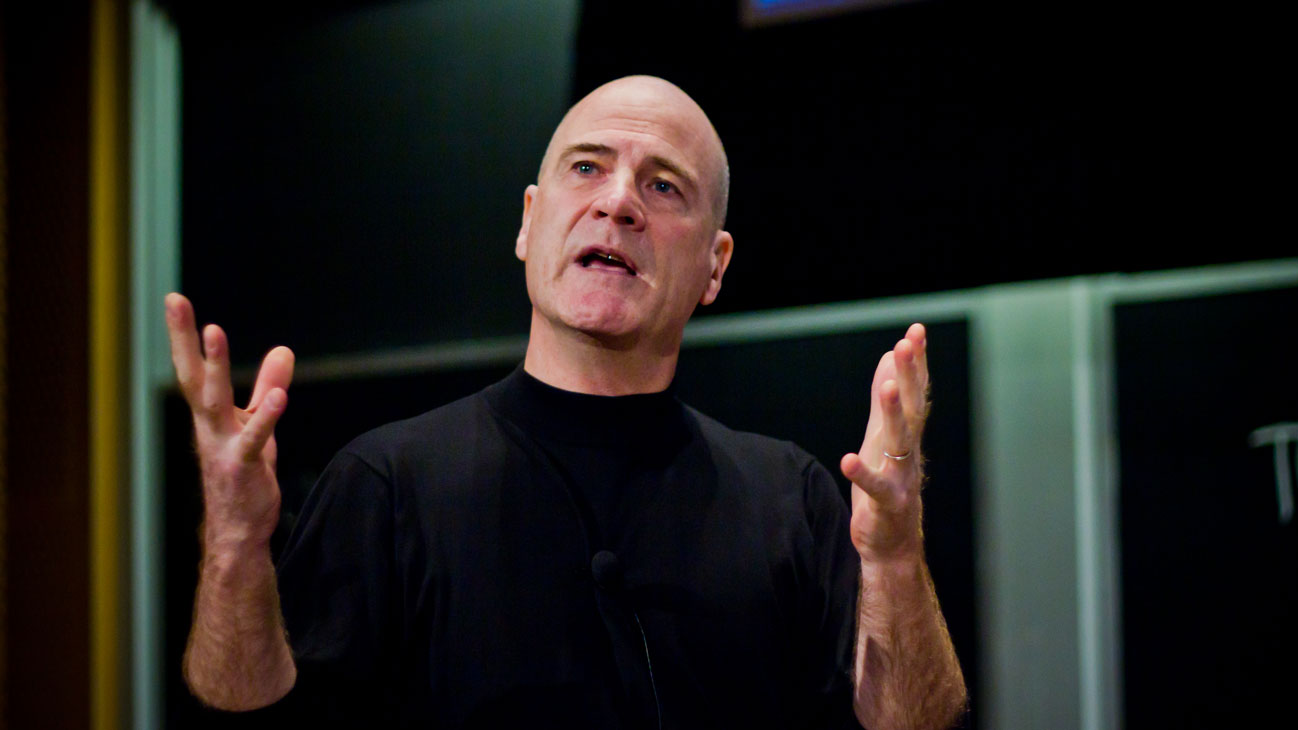

Leading cultural anthropologist Grant McCracken is a research affiliate at MIT and the author of Chief Culture Officer and the recent book, Culturematic. Here, McCracken writes for the Harvard Business Review on the phenomenon of Twitter and the cultural “disruption” it is an example of:

I missed Twitter. I first heard about it when everyone did in 2006. And I started an account in a knee-jerk way. But I didn’t grasp it. In those days, I would just stare at the entry box and think, “What?”

Now of course, I pretend Twitter struck me as an irresistibly good idea the first time I heard it and that I was an early champion. I have forgotten and concealed the early days, the days in which I had no clue.

There’s a convenient forgetting going on out there. Our lives are now filled with a stream of disruption, things that are new and strange. Whatever our first reaction, we now like to pretend we were early adopters and enthusiasts. Call it “disruption denial.”

The fact of the matter is our professional lives now churn with change. Markets change. Technology changes. Consumers change. Channels change. Competitors change. This is an era of disruption. Not disruption as the occasional event, but disruption as the constant, chronic condition of our professional lives. You would hope that we were getting better at understanding and managing change. And sometimes we are. Too often however, our response is to ignore and forget change, to fake our way through it, to pretend an engagement and a mastery we do not have. And that’s bad. That means we are not getting better at change, but steadily worse. We are denying disruption, instead of adapting to it.

We seem to adopt and adapt to something like Twitter by stages, a little like Kubler-Ross’ five stages of grief. Except in this case, it’s a passage from confusion to congratulation. Self-congratulation.

Stage 1. Confusion. We don’t quite get it. We sign up for the new app. We give it a whirl. Not really getting it. By this time, gurus are reassuring us that Twitter is the greatest thing ever. But that doesn’t help. We’re still not getting it. And so we turn to Stage 2.

Stage 2: Repudiation. It turns out there are lots of people who don’t get the new technology and now social life is a little like a competition to show that we’re not “falling for it.” At this point, there can more social capital in saying that we don’t like the tech than that we do.

Stage 2 is marked by snappy one-liners. With the practiced ease of stand-up comedian, we can now be heard saying stuff like, “Twitter. What could I possibly say in 140 characters?” Or, “FourSquare? Why would I want to be mayor of my living room.”

Stage 3. Shaming. This is when we are so persuaded that we’re right and the new innovation is wrong that we are prepared to make fun of the credulous among us. I was on the receiving end after I gave a presentation on new media to a large advertising firm. When I finished, three planners took turns patting me on the head and telling me, “This Twitter thing. It’s just a fad. Give it a couple of months and it will go away.” We heard a lot of this sort of thing about Pinterest in the early days. Now it’s valued at $2.5 billion.

Stage 4. Acceptance. By this time, the innovation is taking off. The middle adopters are signing on. It’s clear now even to us that Twitter is here to stay. Confronted by accomplished, irrefutable fact, we cave in and sign on.

And that brings us to Stage 5.

Stage 5. Forgetting. This is where we destroy the evidence. Now we are inclined to act as if we always understood and approved of a world installed with new innovation.

Most often, we don’t make this as a formal decision. We don’t say, “I was wrong for the following reasons. And I am converting for the following reasons.” We just slide into a new way of thinking. One minute, we are too smart to be fooled by Twitter. The next we are fully on board. It’s a like high school. We hate that new haircut until suddenly we have the new haircut. We are captives of what Mark Earls calls “the herd.”

Our motive is clear enough. We don’t want to be the person who doesn’t get it. This is amnesia performed to save face. It’s a lie will tell ourselves about ourselves for ourselves.

This is, of course, entirely human. But at some point we have to snap out of it. We have to accept that change is the new structural reality of our lives and we have to begin a new set of problem solving routines that can put things right (or righter).

When you first lay eyes on something like Twitter, don’t react emotionally, don’t reject it out of hand. And when you go back to correct those first impressions, don’t conceal the evidence so that it looks like you (we!) were right all along.

Instead, do a careful, thoughtful analysis, for and against the innovation. Write it down, and consult it every time “Twitter” comes up and enter a new, corrected assessment of where the innovation is and where it might end up. Keep doing this until, as in the Twitter case, we find ourselves 6 years down the road and can look back to see what we got right and what we got wrong.

This is one way to learn to with disruption. I would love to hear your thoughts. What are you doing to adapt to the new reality?