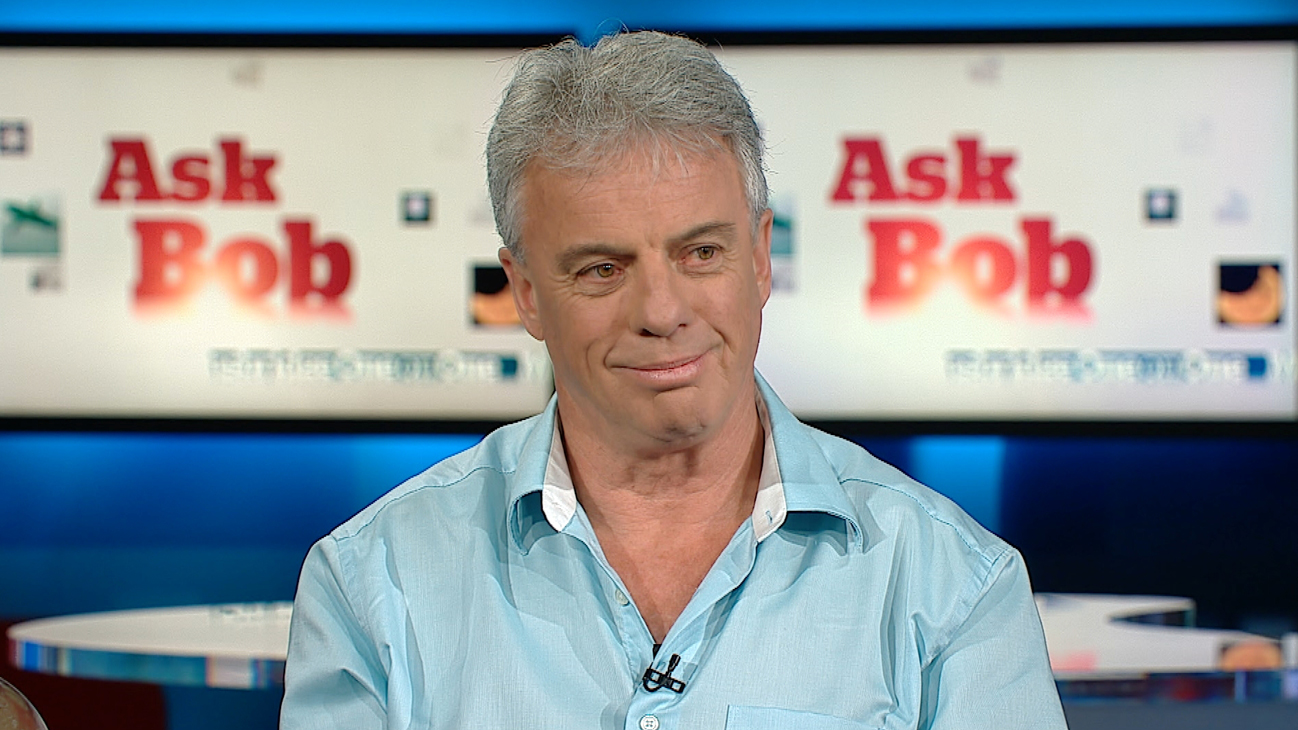

Bob McDonald, host of CBC Radio’s Quirks & Quarks, details the intense experience that awaits famed Canadian Astronaut Chris Hadfield as he returns to Earth from his five-month mission in space today:

The final segment of Canadian Astronaut Chris Hadfield’s mission, the return to Earth on Monday evening, will be the most difficult of all.

As he plunges into the atmosphere, he will transform from a free floating body to a heavy prisoner of gravity.

For five months, Chris has not sat in a chair, slept on a bed and barely touched his feet to the floor. His home in space, the International Space Station, is a weightless world where everyone and everything is in a constant state of free fall.

Astronauts and cosmonauts float around like Peter Pan in any direction they choose, performing slow motion acrobatics with just a slight push of the fingertips.

Now, after almost five months of this freedom of movement, he and his two crew mates, Tom Marshburn and Roman Romanenko, will don their Russian space suits and cram themselves, shoulder to shoulder, into a small Soyuz capsule only three-and-a-half meters in diameter. It’s so small, they can’t straighten their legs.

After departing the station, they will take pictures of the complex from the outside, then spend the next three hours adjusting their orbit into an elliptical shape, with a low point over Kazakhstan.

A Soyuz landing is very different from those of the American space shuttles, which have now been retired. The shuttles had wings and flew into the atmosphere as hypersonic gliders, touching down gently on a runway. For shuttle passengers, the transition from weightlessness to normal body weight was gradual and smooth throughout the entire landing.

A Soyuz falls from space like a meteor.

Beginning on the other side of the planet, an upper section of the Soyuz, called the orbital module, is detached and sent off to burn up in the atmosphere.

Then the craft is turned around with its rocket engines facing forward. The engines are fired for a precise amount of time to slow the spacecraft down, so it begins a long descending arc towards the ground.

Then the propulsion module is discarded, leaving the three crew members flying backwards in their small insulated capsule.

Eight thrusters on the outside of the capsule steer the vehicle and make sure it is on course, but basically, the craft is falling to Earth like a stone from a great height at 28,000 km/h, or 10 times the speed of a bullet.

For the next half hour the crew will remain weightless, as they were on the Space Station, but then things quickly start getting rough.

The first sign of hitting the atmosphere is dust and any free-floating objects in the cabin settling to the floor behind their backs. Then they feel their bodies being pushed into their custom-fit seats.

That pressure quickly increases, as the capsule plunges into thicker layers of the atmosphere.

Air around the spacecraft begins to glow as its molecules are torn apart by the friction from the tremendous speed, until a flaming fireball – thousands of degrees hot – completely engulfs everything.

From the ground, a long, bright, flaming streak is seen racing across the early dawn sky.

Cocooned inside, the crew feels the strange sensation of weight returning to their bodies. But then that weight continues to rapidly grow, surpassing their normal weight, and reaching up to four-and-a-half times what they feel on Earth.

If the guidance thrusters didn’t do their job, the capsule could fall on a much steeper ballistic trajectory that creates more than eight times the force of gravity on the crew, almost to the point of blackout. Friction with the atmosphere slams the brakes on hard.

Organs of balance inside the ears, which have not experienced gravity for five months, are suddenly overwhelmed with the powerful g-forces, creating sensations of dizziness, disorientation and nausea.

Once through the fiery part of the re-entry, the astronauts receive a hard jolt into their seats as the first two of four parachutes pop out to slow their descent further.

Under the chutes, the capsule may start swaying and spinning, generating more dizzying sensations for the crew’s overloaded balance systems. The crew must keep their heads still, eyes straight ahead, to fight the nausea.

Then, there is a short drop and another jolt as the final main parachute is deployed – the most reassuring sight to the crew as it brings them all the way to the ground.

Well, almost. Since these capsules come down on land rather than water, as the Apollo moon capsules did, a parachute landing is pretty hard. So just before touching down, when the capsule is only a metre above the ground, six engines (actually explosive devices) fire straight down to create a cushion of air that softens the landing. Shock absorbers built into the seats absorb the final thump onto planet Earth.

Astronauts have described a Soyuz landing as similar to surviving a train wreck. It’s rough, but it is the most reliable system that has been working since the beginning of the space program.

With heads that feel like bowling balls and arms that feel like logs, the three crew members remain seated, until bright sunlight and cool morning air rushes in when the hatch is opened, and smiling faces of Earthlings welcome the space travelers back to their home planet.

They have to be carried out, placed in reclining chairs and covered in blankets to greet their comrades. Walking will come later and it will take weeks to fully regain their balance and return to a life where gravity rules.

Chris Hadfield will be home – but Peter Pan no more.