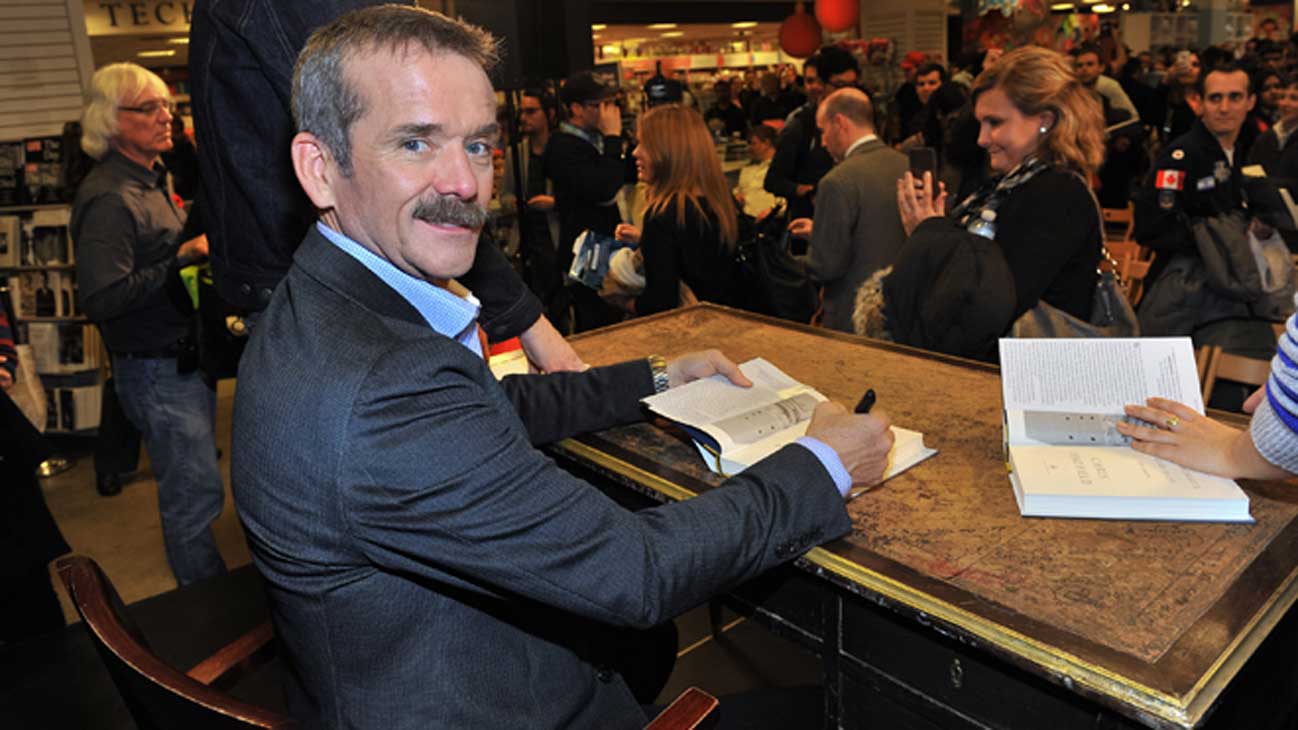

Since returning to Earth, Col. Chris Hadfield has become one of Canada’s most widely read authors. His book An Astronaut’s Guide to Life on Earth was on the New York Times bestsellers list. So too was You Are Here, a visual essay that combined photos from space and Hadfield’s commentary. Canada’s famous astronaut has since published a children’s book, The Darkest Dark, but before he embarks on a fourth book, Hadfield had a hand in co-founding the Canadian Children’s Literacy Foundation alongside other notable Canadians like former prime minister Paul Martin and Indigo CEO Heather Reisman. Maclean’s spoke with Hadfield to learn more about the initiative, find out where Canada is lagging in children’s literacy, and hear what Hadfield plans to write about next.

Q: How did you get involved in co-founding the Canadian Children’s Literacy Foundation?

A: I’ve been an author for four years now. I’ve been able to speak to a lot of writers and publishers in the business. Heather Reisman approached me about a year ago about literacy issues in Canada, and [said] that she was thinking of doing something beyond the Love of Reading Foundation. We’ve been meeting about it for quite a while, looking into the issues and how to address some of the shortcomings we have in literacy in Canada.

Q: Was there any experience from your life that got you interested in this issue?

A: Scientific literacy is one of the underpinnings of everything I do. It’s why we run the Generator Project. It’s why I work with schools. It’s why I teach at university. I do a lot of outreach to try and improve general scientific literacy, but the core of all scientific literacy is just literacy.

You can delude yourself into thinking the actual numbers on literacy in Canada are better than they are depending on where you live and who you talk to. From speaking with experts in the field, you get an actual sense of what is our national literacy level. Some of the numbers end up being surprising.

Q: What’s Canada doing wrong that this foundation aims to fix?

A: In some areas, we do a magnificent job of ensuring high levels of literacy and in some areas, we do not. This foundation will address that.

Providing books is obviously worthwhile, but so too is trying to find out the science behind learning to read. What age is critical? What influences are important? How do you make it a priority at the age when it’s important in their development? When I was speaking with Heather, that’s what I’ve been talking about: making sure we’re addressing the science behind it.

Everybody’s got a limited set of resources. If you can do the research to show where is the most effective application of resources—whether it’s money or books or both—and you give that money to organizations responsible for providing it, then you have a good chance of having an impact.

If it’s just a matter of putting books in people’s hands, it’s a relatively straightforward solution, but that may not be it. If you look at first-generation Canadians whose parents may not speak English or French, how are they putting literacy in front of their children? Or if there’s a situation where reading is not valued, find out why.

Q: You are obviously a pretty smart guy but did you ever struggle as a kid with reading?

A: I was raised in a household that really valued reading. I was lucky enough to be part of school system that supported it as well. It wasn’t an issue for me growing up. It was one of things that was very highly regarded at home and in school. But that’s by no means uniform at all homes nor at all schools.

Q: As an author, what’s more gratifying: seeing a stranger in the park reading An Astronaut’s Guide to Life of Earth, or seeing a child at a bookstore leafing throughThe Darkest Dark?

A:One hopefully leads to the other. I’ve had countless people come up to me and say, “My husband never reads books, but he read yours.” If my influence can be to get someone to read a book when they normally don’t, I’ll take that as a positive. But that door is only cracked open if that person is confident enough to read.

It’s like learning a bicycle. If you haven’t learned to ride a bike by the time your peer group has, then suddenly it’s an embarrassment and you’ll avoid opportunities where you’re expected to ride a bike. And then it starts shaping your behaviour. Reading is much subtler, but much more destructive if you have not—for whatever reason—learned to read by the time you should.

Q: What’s the last book you read?

A: I just finished an old Dick Francis book. I’ve read the entire Dick Francis series. To me, it’s like eating popcorn. I also just finished The Cradle of Humanity by Mark Maslin. It’s about what drove the speed of evolution.

Q: And will you be writing any more kids’ books?

A: I’m intending to write a fourth book. I think it will be a young adults book. What I’d like to do is take the ideas in Astronaut’s Guide to Life on Earth, but a guide to life is different for a 10-year-old than it is for a 30-year-old. Some of the ideas and potential transferable skills are slightly different at 10 than they are at 30.

The transition of understanding our world happens at about eight years old, so helping someone as young as eight to see the opportunities that lay in front of them—and recognize that those opportunities come from within—I think would be a worthwhile book to make.