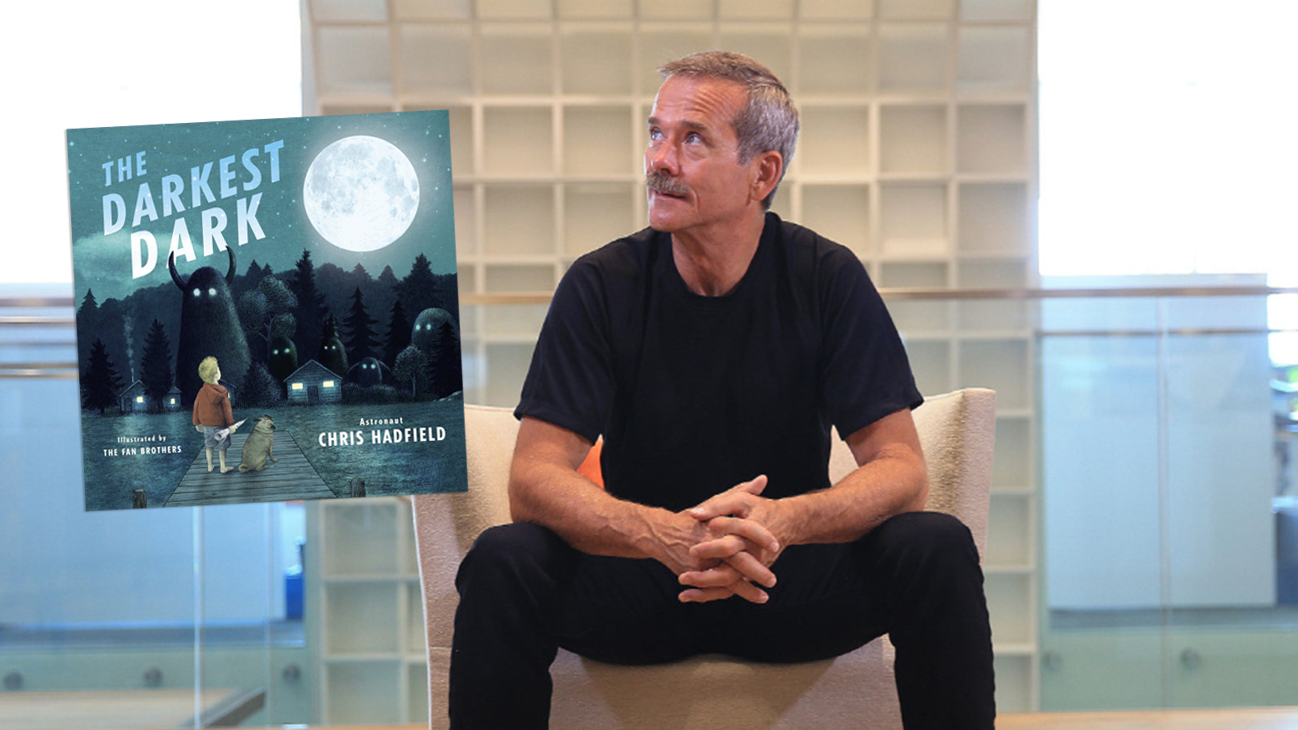

“Good morning, Earth!” That is how Colonel Chris Hadfield—writing on Twitter—woke up the world every day while living for five months aboard the International Space Station. Through his 21-years as an astronaut, three spaceflights, and 2600 orbits of Earth, Colonel Hadfield has become a worldwide sensation, harnessing the power of social media to make outer space accessible to millions and infusing a sense of wonder into our collective consciousness not felt since humanity first walked on the Moon. Called “the most famous astronaut since Neil Armstrong,” Colonel Hadfield continues to bring the marvels of science and space travel to everyone he encounters. Colonel Hadfield spoke to the CBC about his newest book, the children’s story, The Darkest Dark:

Teacher. Musician. Pilot. Astronaut. Internet legend.

Chris Hadfield is all these things and more — and now he can add “children’s author” to that list, too.

Hadfield’s new book, The Darkest Dark, tells the semi-autobiographical story of a young boy named Chris who wants to become an astronaut, but must first overcome his fear of the dark.

Hadfield told BC Almanac host Gloria Mackarenko all about the new book, as well as answering questions from listeners about inspiring young people, going to Mars, “oh crap” moments on the International Space Station and more.

Here are just some of the highlights of what Hadfield had to say:

On writing a children’s book

As an astronaut, I spoke at schools everywhere in the country for 21 years with the Canadian Space Agency, speaking to kids of all ages but including little ones — preschool and kindergarten, sometimes.

And some of the common threads of ideas that you end up talking to young people about as an astronaut — you see that there’s some thoughts in there that might be useful or that might be worth them trying to internalize.

And that was all the genesis of this book, both being a parent but also having spoken to so many kids at schools: how to deal with fear, how to become confident and brave enough to do the things that you’re starting to dream of, and then, how to let that shape your life.

On asking kids what they want to be when they grow up

When people say to a child, what do you want to be when you grow up, I really think that’s a bad way to phrase the question. Because number one, they don’t know what all the choices are, and two, it puts them on the spot to answer a question they don’t have the capability to answer yet.

I think the better question to ask is, what do you want to change in the world? That’s what you should ask a young person.

What are the issues that you think you would like to change? Because then, instead of just giving them a set of strictures of a job that they’re trying to fit themselves into, instead they recognize that the real part of being an adult is trying to do something that is important to you, that changes something you’re dissatisfied with, that leaves a positive impact overall.

On the relationship between art and science

Art and science don’t know they’re separate. That sounds silly, but we put them in separate parts of the newspaper. And yet, if you play music through an oscilloscope, is it art or is it science? Or if you look at a rainbow created through a prism, which one is it?

Or if you’re outside on a space walk, which is sort of on the very tip of the spear of what technology can allow us to do, and you go through the northern lights, so that they ripple past you — very scientifically, it’s electromagnetic energy fluorescing with the various levels of the electron energy of all the individual elements of the upper atmosphere.

But it’s also gorgeous. It’s beautifully artistic. And I think you should notice both all the time, and that they’re completely interwoven.

On ‘oh crap’ moments in space

Nobody ever wants an astronaut to say, “Oh crap.” Those aren’t the words you want to hear.

It may sound unrealistic, but I’ve tried to spend my whole life turning myself into someone who would never have to say that out loud.

It’s why I studied all those years in university and became a test pilot and studied 21 years as an astronaut: so that no matter what happened up there … even though that wasn’t what we expected, it was somewhere within the scope of what we were ready to deal with.

And really, you’re sort of champing at the bit. You know it’s going to be a really, really hard test, but you’ve prepared for it. And that’s a wonderful way to approach a problem.

No astronaut launches for space with their fingers crossed. That’s not how we get ready for things. We are eagerly looking forward to the challenge of what’s going to happen.