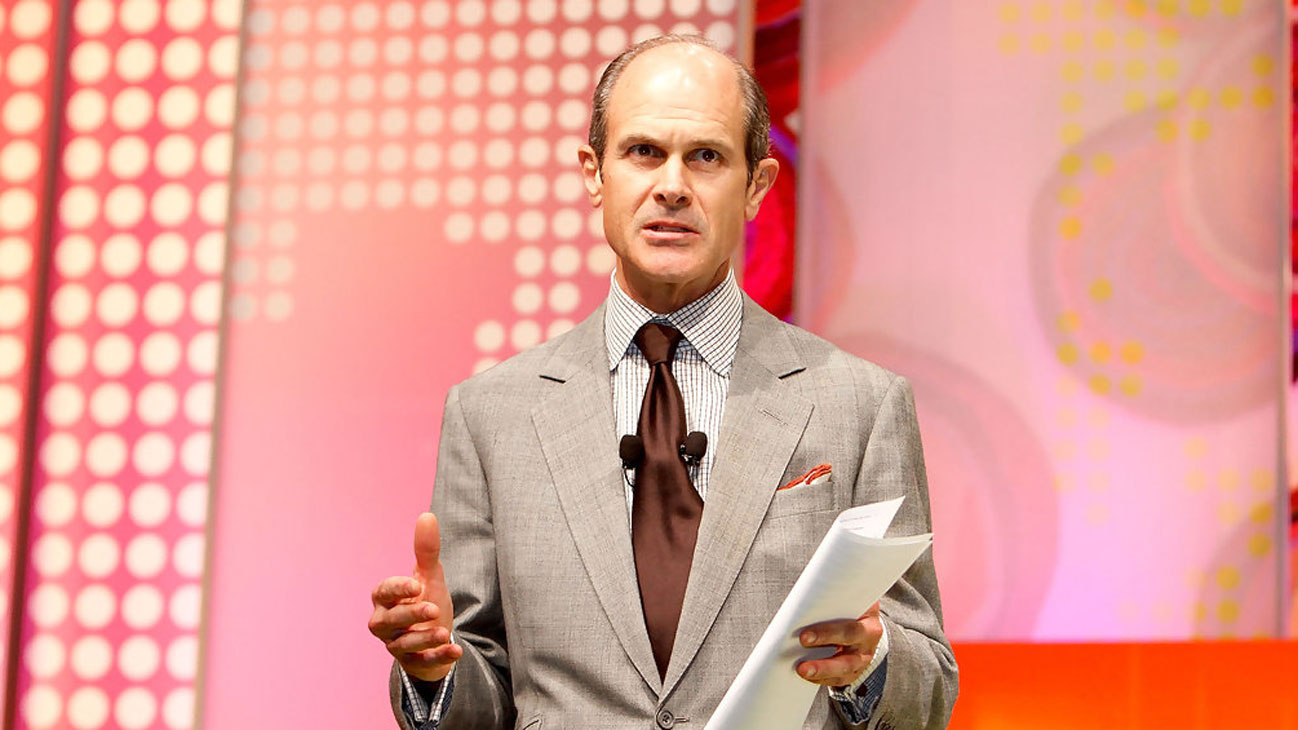

Millions of eyes and ears count on―and respect―Geoff Colvin’s insights on the key issues driving change in business, politics, and the economy. The senior editor of Fortune magazine, and named by Directorship magazine as one of the “100 Most Influential Figures in Corporate Governance,” Colvin draws on his years of insider access to top government figures and high-profile executives to share effective leadership strategies, and provides his unparalleled perspective on the business climate of today…and tomorrow. In this recent article for Fortune magazine Geoff looks at how more and more companies are saying goodbye to public shareholders, activist investors, and regulators, and why it’s so easy to go—and stay—private:

Why can’t you buy Uber stock? No investment banker could fantasize a company more perfect for an IPO: young, world famous, taking in billions a year, operating in more than 400 cities around the globe (and already profitable in over 80 of them), growing at triple-digit rates. Investors would trample one another for shares. So why won’t CEO Travis Kalanick seize this moment and achieve the dream of every startup founder, going public?

The answer is simple. Kalanick doesn’t need or want your money. There’s no need to take on the hassles of being publicly traded when private sources of capital can supply all of Uber’s needs. Much of the money comes from investment funds; some comes from strategic investors such as Microsoft , which kicked in $100 million last year. Uber raised $2.1 billion last December on terms that valued the company at $62.5 billion. Such paper valuations may of course be fleeting (see Theranos—touted $9 billion valuation, smoke and mirrors). But if you believe such heady guesstimates, then Uber’s virtual sticker price would make it more valuable than at least two companies in the Dow Jones industrial average, Caterpillar CAT and Travelers, and more valuable than another noted company in the transportation business, General Motors GM —which has been on the Fortune 500 every year since the list’s inception in 1955. By some measures Uber has already joined America’s corporate elite. Yet Kalanick says it’s at least “a few years” from going public.

Uber, No. 1 on our new ranking of America’s most important private companies, is an extreme example of a significant trend. American business is increasingly shunning the traditional marker of making it—being publicly traded—in favor of private ownership. While the total number of U.S. companies continues to grow, the number that are traded on stock exchanges has plunged 45% since peaking 20 years ago (see chart, next page). IPOs, once a bubbling indicator of U.S. business dynamism, dried up after the dotcom bust in 2000 and have never recovered, even though today’s economy is far larger. Some public companies, meanwhile, are repenting of their choice and returning to private ownership. Many other companies are simply staying private.

The shift reflects a world in which the supply of and demand for capital are changing at the same time that the ways in which companies create wealth are changing. New market conditions plus new rules and regulations are re-weighting the incentives that business owners face. Public companies aren’t going away, but they’re becoming fewer and bigger. The result is an environment much different from that of the past 50 years, giving larger roles to private companies with their own distinctive ways of doing business, paying employees, and managing for the future.

You know something big is happening when such high-profile public companies as Dell and Safeway go private. They rave about their newfound ability to invest for the long term and focus on the business rather than on Wall Street, but the truth is that both were motivated in large part by that modern scourge of public companies, the activist investor. “Public company boards are scared to death of activists and will do all kinds of things to avoid proxy contests,” says a top executive at one of the largest private equity firms, speaking on background. “It’s a whole new phenomenon of the past four or five years.” PE firms took both of those companies private (Silver Lake with Dell, Cerberus and others with Safeway). Activists have pushed plenty of other public companies into private hands in recent years—PetSmart, the Rockwood chemical company, and a raft of smallish software firms, for example.

In an informal online survey recently, Fortune asked CEOs, “Do you agree or disagree with the following: It would be easier to manage my company if it were a private company rather than a public company.” Though we have only preliminary results so far, the message is clear: 77% agreed with the statement.

Public-to-private deals have waned for the moment because public market valuations are too high. The larger trend now is not going private but, like Uber, refusing to go public. The reasons, which extend way beyond activists, show why widening private ownership is a trend with legs and why public-to-private deals will come back when prices subside.

The main reason companies go public, though far from the only reason, is to raise capital. In the old industrial economy based on factories and machinery, the attraction of broad-based financing was obvious. The capital requirements could be huge, and because the assets were illiquid, many investors wanted only a small bit of the risk. But today many major companies don’t need much capital. Think of Apple Alphabet Microsoft, Facebook and Amazon , five of America’s seven most valuable companies. They manufacture virtually nothing and are so profitable that the very last thing they need is more capital; among them they sit on over $400 billion in cash and marketable securities. It’s what the McKinsey Global Institute calls an “asset-light” business model, and companies using it now account for 31% of all the profits of Western companies vs. just 17% in 1999. “Value is increasingly created from patents, brands, trademarks, and copyrights rather than industrial machinery or factories,” says MGI. On Fortune’s inaugural list of the 25 Most Important Private Companies, 15 don’t deal in physical goods at all.

That recent online survey reinforces the point. Fortune asked CEOs if they had all the cash they needed to fund investments. Only 8% said no.

While the demand for capital is in secular decline, the supply of it is mushrooming. As China and India plus other emerging economies (including high performers like Indonesia and Nigeria) become more prosperous, they contribute to what former Fed chairman Ben Bernanke calls “the global savings glut.” More capital is seeking a home than ever before. One result is that private equity and venture capital firms, just like today’s infotech giants, hold more money than they know what to do with. Their “dry powder”—funds committed by investors but not yet invested—rose to $1.3 trillion last year, says the Preqin research firm. The “biggest challenge facing the industry in 2016,” says the firm, is “valuations”; too much capital is chasing too few target companies, so buying companies at reasonable prices is tough.

Besides, even private companies that need capital face an enticing alternative to giving up equity: They can borrow money at the lowest rates ever, thanks to the savings glut plus easy money policies across most of the world’s GDP. Unilever UL -0.96% recently issued bonds with a 0% coupon. Smaller companies have to pay more, but their rates are still historically low. And in the U.S. and many other countries, interest payments are tax-deductible.

Now combine those factors: Companies are less likely than they used to be to need much capital. They can borrow money without giving up ownership at the lowest cost ever. If they need to sell an equity stake, PE and venture firms are so flush with cash that they may be lined up outside the door. And while public financing may seem necessary for a company to achieve truly dominant scale, it isn’t. Look at many of the companies in our ranking: Vanguard, Fidelity, Bridgewater Associates, Cargill, Bechtel, NFL, Mars, PwC—each the biggest or among the biggest in its industry.

So why go public? Especially when you consider the many disadvantages, quite apart from activists. The process itself is costly. Underwriting and registration costs average 14% of the funds raised, says IPO expert Jay Ritter of the University of Florida. Offerings are usually underpriced so as to produce a first-day “pop,” but that means lots of money is left on the table, on average about 15%, say researchers. Public companies face additional rules, notably those imposed by the Sarbanes-Oxley and Dodd-Frank laws in the U.S. Economists figure the costs may be enough to tip the balance against going public for smaller companies. In any case, the many disclosures required of public companies are rich with information for competitors to study. Then there’s all the time managers spend dealing with Wall Street analysts and potentially thousands of shareholders.

Being public can become a wild, uncontrollable ride for a young company. Consider LendingClub, which went public in December 2014. The stock surged, then plunged though the company was hitting its ambitious targets. In May the board, led by independent directors, fired CEO Renaud Laplanche because he urged them to approve a LendingClub investment in a company without telling them he had personally invested in it. LendingClub LC -2.91% stock was recently down 83% from its IPO debut.

Private firms avoid those headaches and, if they connect with a PE firm, may gain other advantages. “PE exists and delivers because the governance”—the mechanism of owners overseeing managerial decisions—“is superior, in allocating capital above all,” says a PE chief. “When public companies run out of growth, they buy back stock at the worst times.” He’s right; they’re doing it now, when valuations are high. “We invest more in moments of dislocation.”

A PE firm can also bring broad managerial wisdom that many companies lack. Consider Tibco Software, one of those smallish software outfits that went from public to private after an activist demanded changes in response to weak results. Tibco sold to Vista Equity Partners, and founder Vivek Ranadivé ceded the CEO role to COO Murray Rode. “What surprised me most was the nature of the relationship with our private equity investors,” Rode says. “When you’re aligned with such a firm as theirs, it’s a bit like a golfer having a swing coach. Even if you’re a good golfer, it helps to have a swing coach who says do this, not that. Vista has a well-developed process of sharing best practices from its portfolio software companies to help your business. It spans a range of functional areas—from sales to product management to HR to M&A and leadership development.”

Private ownership can be powerfully attractive to managers on another dimension: pay. At public companies, top executive pay is publicly reported. Few executives like the attention. Worse, boards may hesitate to adopt incentive pay plans that could reward CEOs hugely if they deliver spectacular results, just from fear of how it would look. None of that matters at private companies, where pay plans can offer a CEO far greater rewards if he or she is willing to accept more risks. At PE portfolio companies, “there’s an onboarding bonus and lower annual compensation than at a public firm,” says Bob Nardelli, who oversaw many such companies as an adviser to Cerberus Capital Management and ran one of them, Chrysler, from 2007 to 2009. “You get a percentage of the increase in value. CEO comp is much more variable than in a public company. There’s no pension, no safety net, no long-term medical. You’re a 1099. You leave early, you leave everything on the table.”

Some advantages of private ownership are overstated. Managing for the long term? Maybe, if the company is family-owned. But if it’s PE-owned, that PE firm has an exit in mind, typically five to seven years down the road. Managers can execute a plan that will pound earnings for a few quarters or even a few years; Dell has lost $3.9 billion since going private in 2013, for example. But a version of Mitsubishi’s 500-year plan is not going to fly. Avoiding the public release of financial statements? Not necessarily. Private companies with publicly held debt may still have to file quarterly statements with the SEC, and if a private company wants to buy a public one, it must publish detailed internal data; we know about Dell’s losses from SEC filings connected to its deal to buy EMC.

Still, don’t private companies avoid the pressures of the public markets? Sure, but those PE guys aren’t playing games and can be much more demanding than public shareholders. Family-owned companies don’t face PE deadlines, but internal conflicts have torn many of those companies apart or forced them to sell to another firm or to the public. A conflict between the Ford family and the Ford Foundation, not a need for capital, led Ford to go public in 1956 in the biggest-ever IPO at the time.

Which reminds us that being public still holds valuable advantages. It can enable a founder to raise capital while retaining control, by keeping a majority stake or by issuing multiple classes of stock so the founder controls the voting shares, as Facebook, Alphabet, Comcast, New York Times, and many other companies have done. It also enables founders to cash out while retaining effective control, though they might not sell their shares for many years; Bill Gates is still selling his Microsoft stock 30 years after the IPO. A listed stock and the attendant public disclosures give a company’s suppliers, employees, and customers independent assurance that it’s worth doing business with. Stock options can be highly effective in attracting and keeping managerial talent.

So here’s a sketch of corporate ownership in 2016. In a friction-free economy where information and money move instantly, the best public companies are getting sorted from the rest. Research shows a widening gap between the profits of the top performers and the mediocre ones in an intensifying winner-take-all dynamic. Only the best survive in that environment, resulting in fewer, bigger public companies. At the same time, more companies are staying private, perhaps because they don’t need much capital, or they’d rather get capital from private sources, or they prefer to sell to a larger firm rather than do an IPO; all those trends are growing. Some companies go from public to private through a private equity buyout, after which they may go public again but more likely will be sold to another company, never to return independently to the public markets.

It’s a world in which private companies play a growing role, and the world is changing to accommodate them. States offer a lengthening menu of options for private company ownership—limited liability companies, limited partnerships, limited liability partnerships, professional corporations, and more. Entrepreneurs are creating innovative ways for owners of private companies to trade their shares through new nonpublic venues such as SecondMarket, SharesPost, and Nasdaq Private Market. Staying private is getting easier every day.

It may even be good for the larger economy. One of the enduring drawbacks of public ownership is the so-called agency problem, the misalignment of owners and managers. Top executives at big public companies typically own only tiny stakes and are tempted to enrich themselves in all manner of ways that may harm the other shareholders, whose ownership is often so diffuse that they can’t discipline the managers. That problem doesn’t arise in private firms, where the majority owners are usually either the managers themselves or members of a powerful board of directors. One result is that resources get used more productively. In the aggregate, more private companies could mean a faster-growing economy.

Combine all the forces at work and it’s no surprise that private companies are getting more numerous, bigger, more successful, and more influential. Don’t expect that trend to stop anytime soon.