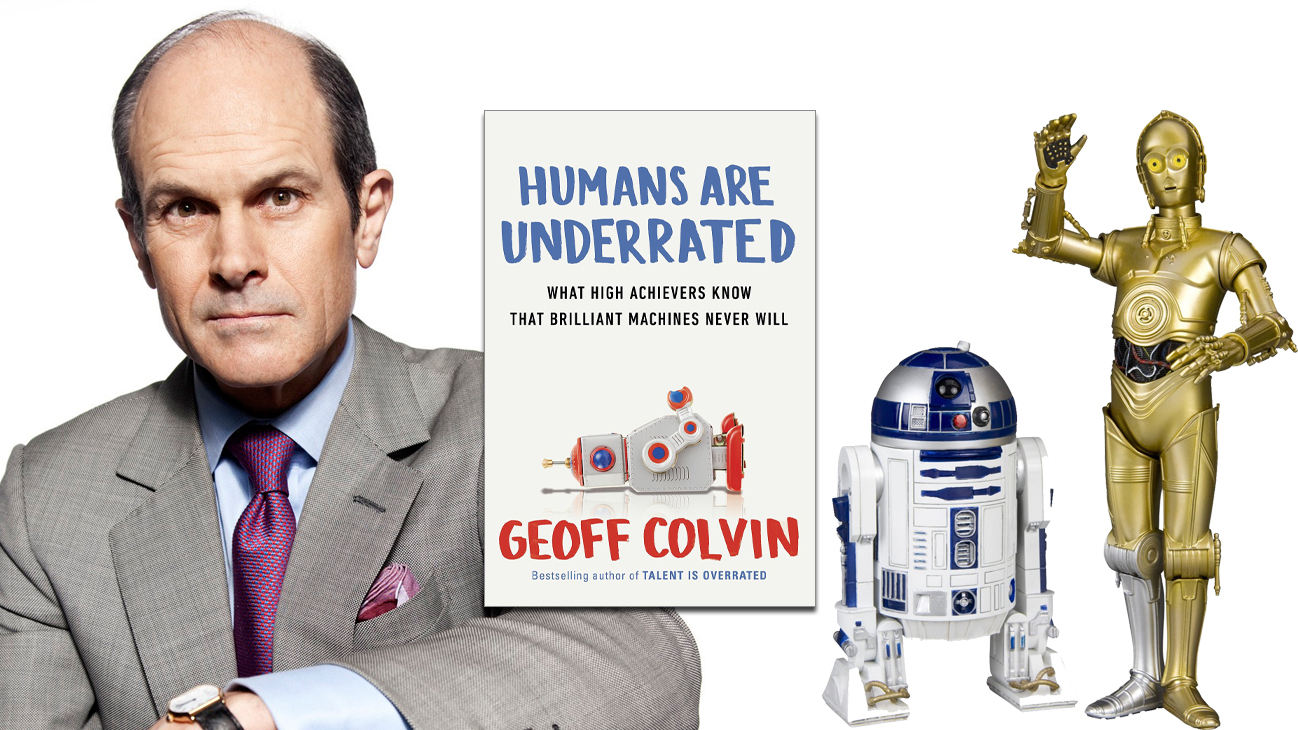

Millions of eyes and ears count on―and respect―Geoff Colvin’s insights on the key issues driving change in business, politics, and the economy. The senior editor of Fortune magazine, and named by Directorship magazine as one of the “100 Most Influential Figures in Corporate Governance,” Colvin draws on his years of insider access to top government figures and high-profile executives to share effective leadership strategies, and provides his unparalleled perspective on the business climate of today…and tomorrow. In this article for Wired magazine, Geoff looks at why robots won’t end up replacing people-power, which is also the topic of his newest book, Humans Are Underrated: What High Achievers Know That Brilliant Machines Never Will.

For workers, educators and policymakers, it has become one of the most troubling questions of our time: what will people be able to do better than computers?

No job seems safe. Computers conduct discovery in lawsuits, sorting thousands of documents faster, more perceptively and far less expensively than human lawyers. They drive cars better than people do. They write articles in papers (without your knowing it) and judge more accurately than people do the danger you pose to others when you cross international borders. They even perform some surgeries more proficiently than a human.

As technology gallops ahead, what will be left for us? That didn’t use to be a problem. Over time and across economies, advancing technology has always increased jobs and raised living standards. But a growing number of economists and tech experts wonder if that will continue. Former US Treasury secretary Larry Summers is among the sceptics. He says that after a lifetime of believing otherwise, he’s “not so completely certain now” that technological progress will be good news for workers. He believes it will be “the defining economic feature of our era”.

The usual approach to divining how humans will add value in the computer age has been to ask what computers cannot do. That’s the wrong approach. Every time we try to answer that question, we’re proven wrong eventually. Mainstream experts have long argued that computers would never be able to translate languages very well or play chess above a mediocre level; as recently as 2004, some very smart economists argued that driving a vehicle was just too hard for a computer ever to manage.

Don’t ask what computers can’t do. As their abilities multiply, we simply can’t conceive of what may be beyond them. To identify the sources of greatest human value, ask instead what will be those things that we insist be done by or with other humans — even if computers could do them. These are our deepest, most essentially human abilities, developed in our evolutionary past, operating in complex, two-way, person-to-person interactions that influence us more powerfully than we realise. Empathy, working in groups, storytelling, social sensitivity, building relationships, leading — these are abilities that we will continue to value highly because we’re hardwired to value them. But only in other humans.

As tech takes over more functions, employers increasingly demand these human abilities. When Oxford Economics asked global employers to name the skills they most want, they emphasised “relationship building”, “teaming” and “co-creativity”. The CIO of a major UK retailer, who oversees a staff of coders and assorted techies, told other CIOs at a private conference that what he most needs now are “people who are empathetic and collaborative… I can’t have a good IT architect who has to be locked in a room.”

These developments cast conventional career advice in a new light. Education in STEM, while valuable, won’t be enough. An advisory group of British educators and CEOs chaired by Roy Anderson, asked to recommend changes to secondary education in the UK, concluded that “empathy and other interpersonal skills are as important as proficiency in English and mathematics in ensuring young people’s employment prospects”. The group urged that these skills be taught to all secondary students, but “learning these starting much earlier in school life”.

Technology is re-ordering the value of skills in a fundamentally new way. As we try to understand how, let’s accept that we’ll never know what computers can’t do. But as technology advances, we can guide our children, our colleagues and ourselves, certain in the knowledge that we humans will continue to value most highly the abilities we find deeply compelling.