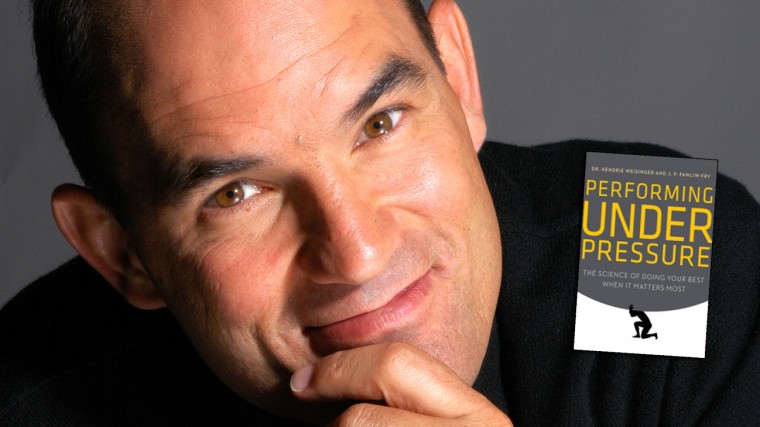

An internationally renowned thought leader on the subject of leadership, performance and managing under pressure, Dr. JP Pawliw-Fry is a performance coach to Olympic athletes and Fortune 100 companies alike. In his book, Performing Under Pressure, Pawliw-Fry (with co-writer Dr. Hendrie Weisinger) introduces people to the concept of pressure management, offering empirically tested short term and long term solutions to help us overcome the debilitating effects of pressure. The Pontiac Daily Leader gathered 13 of Pawliw-Fry’s tips to overcoming challenges:

Let’s get this out of the way right now: Nobody performs well under pressure. A lot of us think we do, but we don’t, or, at least, we don’t perform as well as we could perform.

We may feel more creative when we’re under the gun, but it’s a feeling, not a reality. It’s true that you might be more productive, but the products you create are usually worse.

In their new book, “Performing Under Pressure: The Science of Doing Your Best When It Matters Most,” Hendrie Weisinger and J.P. Pawliw-Fry deliver the sad truth: The difference between regular people and ultra-successful people is not that the latter group thrives under pressure. It’s that they’re better able to mitigate its negative effects.

Or maybe that’s good news, because, as they lay out in the book, handling pressure is a skill, and you can learn it. In the book, they offer 22 tactics for doing your best when the heat is on. We took a deep breath and picked out 13 of our favorites.

Think of high-pressure moments as a (fun) challenge, not a life-or-death threat.

Most people see “pressure situations” as threatening, and that makes them perform even less well. “Seeing pressure as a threat undermines your self-confidence; elicits fear of failure; impares your short-term memory, attention, and judgment; and spurs impulsive behavior,” Weisinger and Pawliw-Fry write. “It also saps your energy.”

In short, interpreting pressure as threat is generally very bad. Instead, try shifting your thoughts: instead of seeing a danger situation, see a challenge.

“When you see pressure as a challenge, you are stimulated to give the attention and energy needed to make your best effort,” they write. To practice, build “challenge thinking” into your daily life: it’s not just a project, it’s an opportunity to see if you can make it your best project ever.

Remind yourself that this is just one of many opportunities.

Is this high pressure situation a good opportunity? Sure. Is it the only opportunity you will ever have for the rest of your life? Probably not.

The fact is, it is realistic to think that additional opportunities will come your way,” Weisinger and Pawliw-Fry write, who encourage you to consider how many people needed multiple chances to ultimately succeed. (We have a few examples here.)

Before an interview or a big meeting, give yourself a little pep talk, they advise: “I will have other interviews [or presentations or sales calls.]”

Focus on the task, not the outcome.

This might be the easiest tactic of all, according to Weisinger and Pawliw-Fry: Instead of worrying about the outcome, worry about the task at hand.

That means developing tunnel vision, they explain. When you keep your eye on the task at hand (and only the task at hand), all you can see is the concrete steps necessary to excel.

For a student writing a paper, that means concentrating on doing stellar research — not obsessing about the ultimate grade, what will happen if you don’t get it, and whether you should have majored in economics after all.

Let yourself plan for the worst.

“What-if” scenarios can be your friend. By letting yourself play out the worst-case outcomes,Weisinger and Pawliw-Fry say, you’re able to brace yourself for them.

What if you’re giving a presentation and you lose all your slides? What if you find out at the last minute you only have half the time you thought you did? What if, three minutes before you’re supposed to begin, you spill coffee all over your shirt?

The key here is that you’re anticipating the unexpected. “It can protect you from a pressure surge by allowing you to prepare for and thus be less startled by the unexpected.” Instead of panicking, you’ll be able to (better) “maintain your composure and continue your task to the best of your ability.”

Take control.

In a pressure moment, there are factors you have control over, and factors you don’t.

But when you focus on those “uncontrollables,” you end up intensifying the pressure, increasing your anxiety, and ultimately undermining your confidence, write Weisinger and Pawliw-Fry. What you want to do is focus on the factors you can control.

In the case of an interview, for example, don’t let yourself think about who else might have applied for the job, ways the manager could be biased against you, or whether the interviewer will like your outfit. The only thing that matters? Preparing to show them you’re right for the role.

Flash back to your past successes.

“Remembering your past success ignites confidence,” Weisinger and Pawliw-Fry write. “You did it before, and you can do it again.”

Once you’re feeling good about yourself, you’ll be better able to cut through anxiety and take care of business.

Be positive before and during high-pressure moments.

In what comes as a surprise to no one (but bears repeating anyway), cultivating a positive attitude goes a long way.

“Belief in a successful outcome can prevent you from worry that can drain and distract your working memory,” Weisinger and Pawliw-Fry explain. “Anxiety and fear are stripped away from the equation, allowing you to act with confidence.” This will work out. You will be great. You’re going to succeed.

Get in touch with your senses.

When you’re under deadline and the world feels like it’s crashing in, you’re particularly prone to making careless errors — slips you never would have made if you’d felt on top of the situation.

To depressurize the situation, Weisinger and Pawliw-Fry advise focusing on the here and now. Tune into your senses, they say. What do you see? What do you hear? How’s your breathing?

Listen to music — or make some.

“What makes this pressure solution so effective is that it reduces the culprit behind choking — increased anxiety,” Weisinger and Pawliw-Fry explain.

By listening to music, you’re able to literally distract yourself from your anxiety. And conveniently, this trick is extremely easy to put into practice: The next time you’re facing a high-pressure situation — a big presentation, for example — spend the few minutes before listening to your pump-up tunes right up until it’s time to take the stage.

Create a pre-performance routine.

The idea here is to create a (brief) routine that you go through in the minutes before you present or perform, Weisinger and Pawliw-Fry suggest.

A “pre-routine” prevents you from becoming distracted (how can you panic when you’re doing your push ups?), keeps you focused, and puts you in the “zone” by signaling to your body it’s time to perform. Here are their tips for creating yours:

– Keep it short

– Do it immediately before The Event

– Include a mental component (reviewing key points, anticipating the types of problems your about to face, etc.)

– Include a physical component (breathing, power posing, etc.)

– Include a visualization of yourself succeeding

– Finish with an “anchor word or phrase that signals you’re ready for showtime”

Slow down.

When you’re in a high-pressure situation, it’s natural to speed up our thinking. Don’t do it!

Moving too fast often leads you to act before you’re ready. You don’t think as clearly as you normally would, Weisinger and Pawliw-Fry observe. You jump to conclusions. You miss key information.

The solution? Slow down. Give yourself a second to breathe and formulate a plan. You’ll think more flexibly, creatively, and attentively, they promise, and your work will be all the better for it.

Squeeze a ball (really).

Yes, “stress balls” are an office cliché — but according to Weisinger and Pawliw-Fry there’s a good reason for that: They work.

One of the reasons you clam up in high-pressure situations is because there’s a constant, unhelpful thoughtloop running through your head. “How am I doing?” you keep wondering, even though you’re doing fine — or you would be, if you could shut your brain up.

That’s where the stress ball comes in. When you squeeze a ball with your left hand, you’re able to activate the parts of your brain that control unconscious responses, while simultaniously suppressing the parts of your brain that oversees self-conscious thinking.

Share the pressure.

Telling someone else about the pressure you’re feeling has been proven to reduce anxiety and stress, Weisinger and Pawliw-Fry report.

But there’s another bonus, as well: Sharing your feelings allows you to “examine them, challenge their reality, and view a pressure situation in a realistic manner.” And it’s likely the person you’re sharing your feelings with will have some feedback, too — feedback you might never have gotten had you stewed solo.

Keep this in mind, too — you may not be the only one feeling the heat. If you’re under pressure about a work project, there’s a good chance raising the issue will make everyone feel less alone.