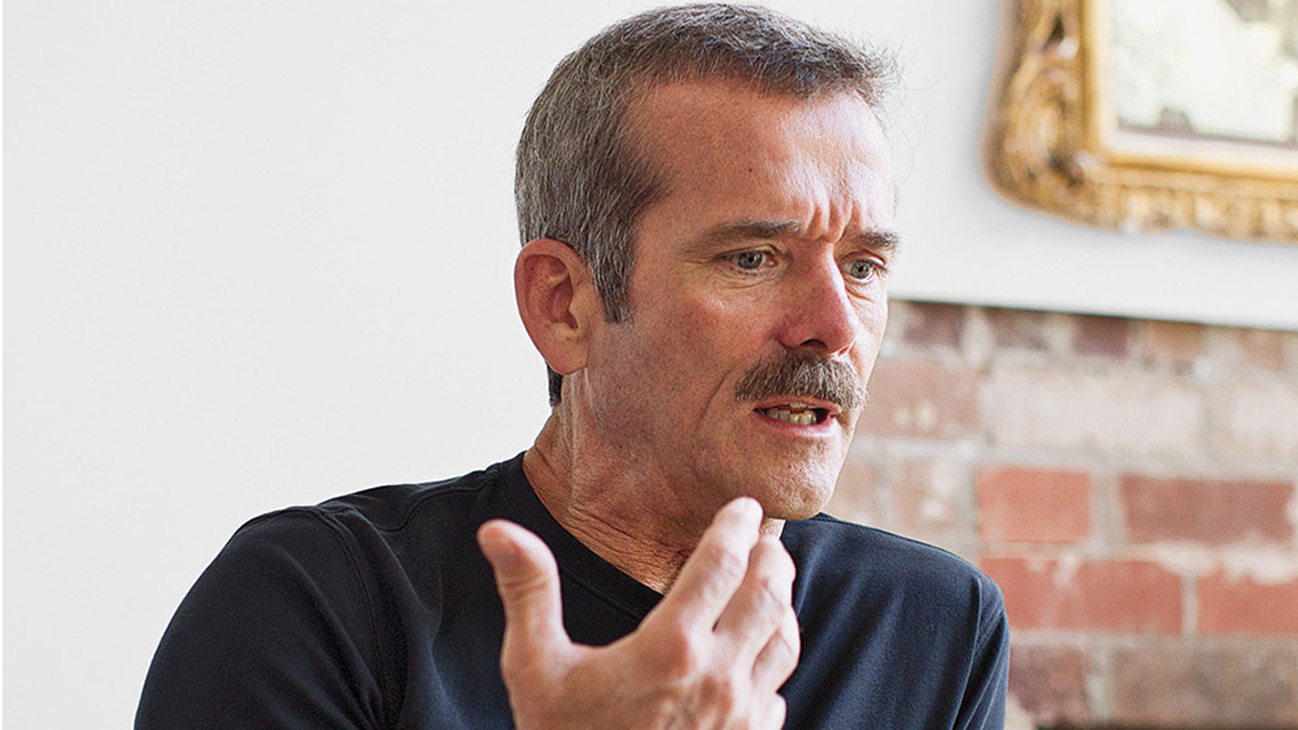

Through his 21-years as an astronaut and three spaceflights, Colonel Chris Hadfield has become a worldwide sensation, harnessing the power of social media to make outer space accessible to millions and infusing a sense of wonder into our collective consciousness not felt since humanity first walked on the Moon. Called “the most famous astronaut since Neil Armstrong,” Colonel Hadfield continues to bring the marvels of science and space travel to everyone he encounters. The Regina Leader-Post recently spoke to Chris about how his talks bridge the gap between science and the arts:

Chris Hadfield has heard the stereotypes about engineers who can’t string together sentences and artists who can’t do math — and he’s not so sure they’re accurate.

Consider Hadfield as an example of someone bridging those two solitudes: a career as a Canadian Forces fighter pilot and test pilot, followed by 21 years as an astronaut including a six-month stint as commander of the International Space Station, in which capacity he got rave reviews for his eloquence in talking, Tweeting and even singing about his life up there.

He’s helped build two space stations and “lived off the Earth” for a full six months of his life. He’s flown in space three times and led a team of astronauts from across the world — while going around that world 2,600 times.

As science fiction author Robert Heinlein observed, “specialization is for insects” — and Hadfield is proving that by going on the road across the country with a multimedia show revealing what he experienced and learned. It plays at the Conexus Arts Centre Dec. 3.

“Science and art don’t know that they’re separated from each other,” he said in a phone interview. “It’s sort of an educational construct that somehow we should separate the two. I’ll do my best to show the vital link between the two and how my life has sorta been an example of that.”

Hadfield will talk about preparing for space flight, how he and his colleagues handled the fear and the stress of a job at which “you only get one shot”, and about how they survived, and lived day-to-day, in space — then came back down to earth.

So delightfully polite that he offers to call back if a reporter is busy, Hadfield says he’s been privileged to have had “a really interesting, unique series of experiences as a human being”.

But to emphasize his point about bridging science and art, he also plans to talk about “the raw beauty of the experience and the perspective that it gives us, as a people and as a nation, and the perspectives on the world.”

“It’s a whole mix, intertwined: the human experience of it and, at least in my view, why any of that matters. And, then, the artistic side: there’s the impact that it’s had and the music that I did with schools across Canada for the Coalition for Music Education, when we were singing with three-quarters of a million kids.”

Hadfield attributes his ability to bridge the gap to having grown up on a farm, where everybody — even the kids — had to be multi-skilled, and in a family where members were not only encouraged to ask questions, but find the answers, then ask more questions.

“Astronauts are generalists; we have to be — especially if you’re living on a space station,” said the proud ex-air cadet, who retired in 2013 from the Canadian Space Agency. “You have to have a huge, broad sweep of capabilities because we have to be able to respond to anything. We have to do surgery on each other … we have to be able to do a spacewalk. But we’re also emissaries because there are only six people in orbit on behalf of seven billion. So the more complete a person can be there, I think the better a job you can do.”

“I’ve always felt it was important to not keep the experience to myself — and do my absolute best to share it.”