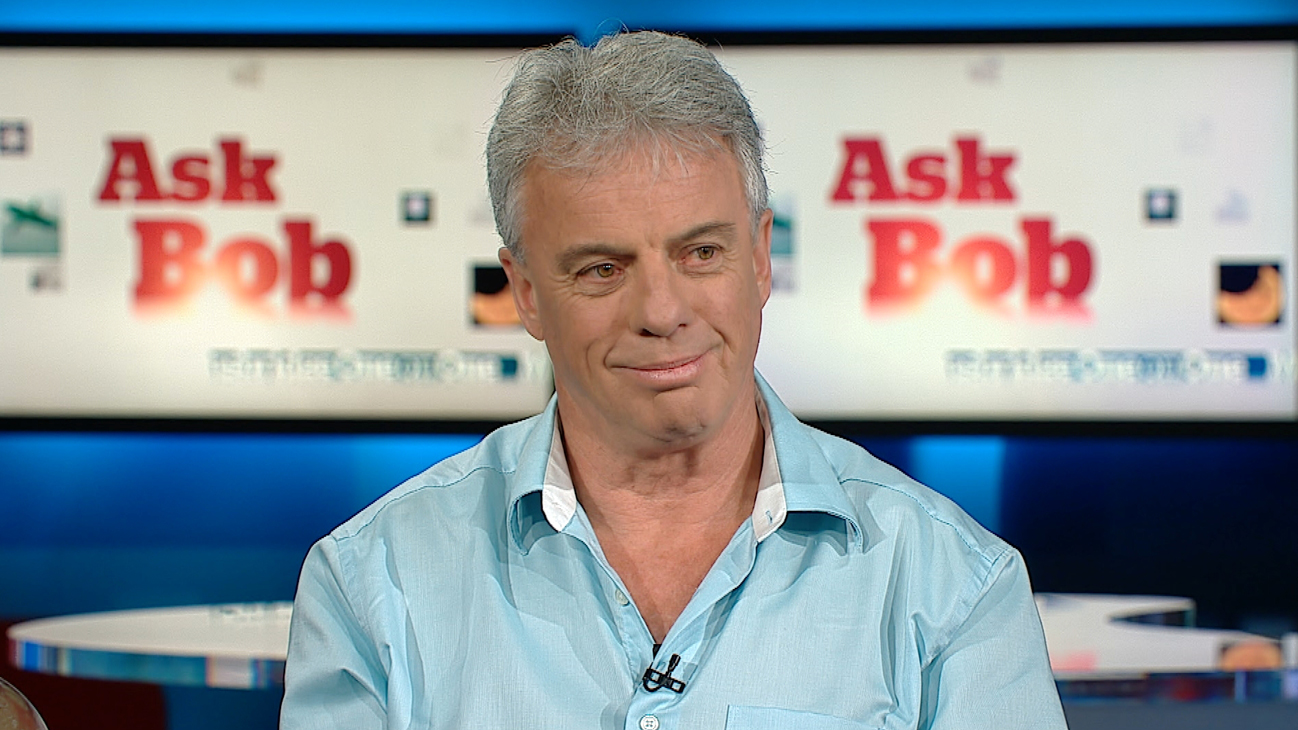

Loved by audiences across Canada for making complex scientific issues understandable, meaningful, and fun, Bob McDonald is in high demand. A fixture in broadcasting for more than 30 years, he is currently the host of CBC Radio’s Quirks & Quarks, the award-winning science program that is heard by 500,000 people each week. Bob looks at our “fight or flight” response, and shows how this natural reflex can be put to good use by our athletes in Sochi:

Fear is as important to an athlete in competition as physical ability. It can trigger a series of instinctive changes in the body that provide quick movement, almost without thinking, which can be very helpful at the starting line. But too much fear can throw the race altogether.

When faced with danger, whether in sports or everyday life, our brain sets off the “fight or flight” response. It’s an ancient adaptation to the fact that, in the animal world, humans are not very well equipped. We have no claws, our teeth are small, we can’t fly, and we can be outrun by just about anything with four legs.

That means we have to rely on our ability to escape danger quickly, even if it means running while injured. The fight or flight response gives us strength we didn’t know we had.

In the prehistoric past, humans evolved so that when we perceived a threat – such as a large animal looking our way for a meal – our body instantly prepared for action:

Pupils dilate to take in as much information as possible.

The Hippocampus in the brain triggers a series of events in the nervous system and in the adrenal system that releases up to 30 hormones into the bloodstream. The best known of these is adrenaline, which, combined with the others, prepares the body for quick movement.

The heart beats faster, and blood is shunted from the extremities towards the major organs, producing a chilling effect.

The immune and digestive systems are shut down to conserve energy.

Extra fuel is provided for muscles through the metabolism of fat and carbohydrates.

Nerve reflexes are quickened.

If the animal pounces, we have to make a quick decision: stay and fight or run as fast as possible.

The animal is big, so we run with a sudden burst of energy, but not before a paw slashes through a leg muscle. A pain signal is sent from the wound towards the brain, but another defensive system in the spinal column blocks the signal, preventing it from reaching the brain. This enables us to keep running, even though we’re injured. If we were to feel that pain, we would slow down and be caught. It’s better to risk injury from running than be killed.

We keep going faster with astounding energy until we reach safety.

Out of danger, our brain rewards us with a rush of dopamine, a neurotransmitter that produces a warm sense of euphoria. It will take an hour for the effects of these powerful body drugs to wear off.

It’s not hard to see how this natural response to flee from danger can be put to good use in competition:

A little bit of fear can help athletes fight their way down an icy track or steep slope.

The extra fuel to the muscles and quicker reflexes can provide an extra boost off the starting line.

Dilated pupils keep the track in focus, even while vibrations shake the head around.

The restricted blood flow in the extremities helps prevent bruising and bleeding during a fall.

And, of course, everyone feels the rush of reward by making it to the finish line.

In sports where the difference between a gold, silver, and bronze medal is measured in hundredths of a second, a slight edge provided by a little bit of fear could make a big difference.

Of course, too much fear can have the opposite effect.

The stress of knowing that this is the only shot you have and the whole world is watching can cause these same reactions to upset the stomach, put stress on the heart and burn up energy before the race even begins. It could even build up to the point where your natural response is to run away from the situation altogether. This can cause even the best in the world to falter in the final competition.

That’s why athletes train through routines, waking up at the same hour, putting on their equipment in the same order, working through warm-up exercises and stretches in ritualistic fashion – mentally going through a routine before starting, so that, on race day, there is a sense of familiarity that reduces the fear of the unknown.

The pros and cons of fear are what make the Olympics such a wonderful competition. It’s as much of a mental game as a show of physical prowess, where a little fear can bring an underdog to the podium while champions fail.

CBC.ca/February 2014