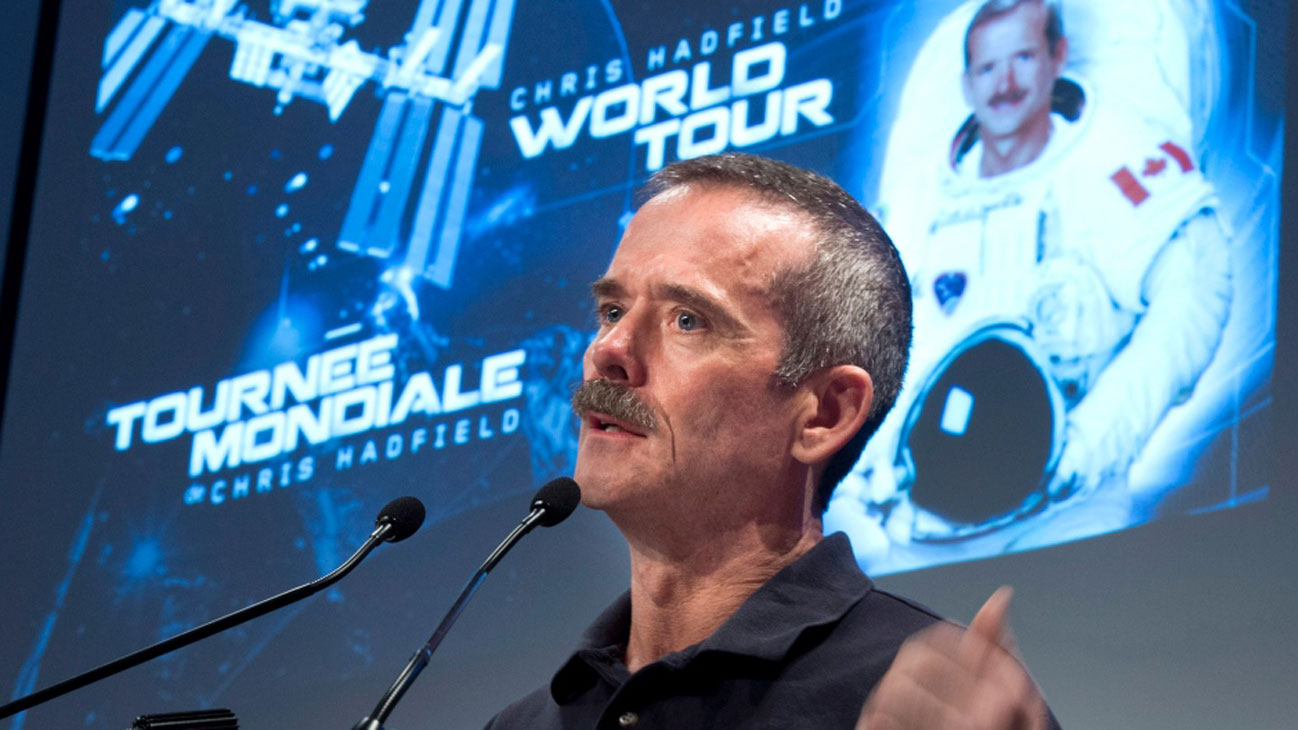

As the famed Commander of the International Space Station, Colonel Chris Hadfield knows a thing or two about leadership. This week, he imparted some of what he’s learned at the Human Resources Professionals Association’s Annual Conference, speaking to a crowd of thousands:

When flying 250 kilometres above the Earth, travelling 7.7 kilometres a second with little margin for error, it’s important that everyone be a leader. So when it comes to developing better leaders on the ground, it makes sense to ask an astronaut.

So it was that Canadian astronaut Chris Hadfield found himself in front of a room full of about 1,000 human resources people, talking about what makes a great leader.

“The greatest gift you can give to somebody is an essential fundamental belief in a purpose within themselves of something that helps give them guidance in the distance – something to help make the small decisions in your life,” Mr. Hadfield said in his speech.

The nature of leadership is changing – decision making has become much more spread out as corporate roles now span the globe, digital tools separate employees from the office and organizations become more cross-functional. At the same time, companies have done a poor job with succession planning and developing leaders, creating a vacuum that is exacerbated by the greying of the work force and by the fact organizations don’t offer skills training in all aspects of effective leadership.

“Organizations and leaders need to become much more agile because decision making is becoming much more distributed – it’s harder to identify who you need to go to, to get things done,” said Rick Lash, director of leadership and talent practice at Toronto-based Hay Group, a management consulting firm.

Five years ago, a chief executive might have been the only driver holding the steering wheel. Today, that same CEO must adapt to holding the wheel with 15 other people, even when directions vary, opinions are at odds and management styles clash. It is about the capacity to lead “diverse, virtual and heterogeneous teams,” Mr. Lash said.

Collaborative leadership can make for better decisions, Mr. Hadfield said in an interview. “There are always different ways to solve given problems. People have different skills, backgrounds and expertise … and if you can give them enough autonomy, time at the wheel, patience and feedback, you may in fact change the direction everybody is going because you see it’s better than the one you originally chose.”

This kind of leadership requires a different set of skills. “The jobs of today may not be the ones we will need when we get into a much more globally based economy,” Mr. Lash said. Organizations have to get better at mapping career paths for people.

Once the organization understands what it wants to look like in the short term, it can better train and provide the right experience that will build the right leadership skills. “You have to know the destination and then work backwards to say ‘What’s the right route and set of experiences that people will need?’” he said.

But few companies get it right, according to leadership consultant Françoise Morissette of Queen’s University Industrial Relations Centre. Succession planning has been “inconsistent and haphazard,” she said, and the downsizing that occurred in the late 1990s and 2000s further eroded the talent pool from which succession planning could take place.

Nearly 60 per cent of companies are facing leadership talent shortages that are impeding their performance, and another 31 per cent expect a lack of leadership talent to impede their performance in the next several years, according to a study by AON Consulting.

Companies created training, mentoring and coaching programs but never really linked them into a meaningful leadership program, Ms. Morissette said.

The key is to focus on collaborative leadership – ensuring that managers and middle managers are trained to take on leadership functions. “Once you switch your focus from event organizer to talent developer, success happens really fast,” Ms. Morissette said.