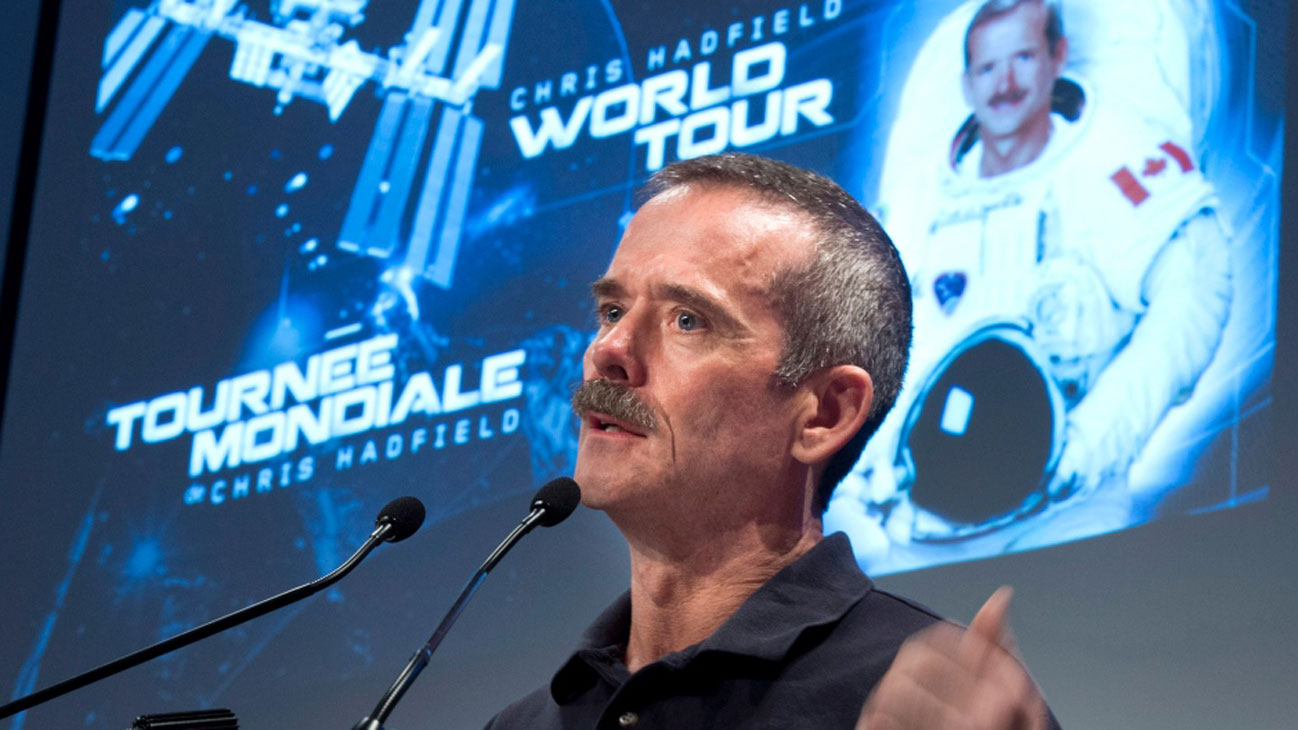

Since blasting off from Kazakhstan in December 2012, Colonel Chris Hadfield has become a worldwide sensation, harnessing the power of social media to make outer space accessible to millions and infusing a sense of wonder into the collective consciousness not felt since man first walked on the moon. Maclean’s magazine gives an advance look at Col. Hadfield’s upcoming book, An Astronaut’s Guide to Life on Earth, and what almost kept him from his mission:

Chris Hadfield tangled with space-program doctors mere months before his star turn as commander of the International Space Station, refusing to submit to surgery in a dispute that came close to scrubbing him from his now-celebrated mission.

The former Canadian astronaut reveals details of the impasse—centering on an intestinal injury dating back to his childhood—in a book due to hit shelves October 29.

“Unbeknownst to me, a new panel of four laparoscopic surgeons had been asked to consider whether it would be a good idea to have what they kept calling ‘a quick look inside’—in other words, to perform exploratory surgery to see whether I really was okay or not,” Hadfield writes in his otherwise even-toned volume, An Astronaut’s Guide to Life on Earth.

“No one had breathed a word of any of this to me or to the flight surgeons at NASA who would be directly responsible for my health while I was on the ISS. The secrecy and paternalism really bothered me. They trusted me at the helm of the world’s space ship, but had been making decisions about my body as though I were a lab rat who didn’t merit consultation.”

The “they” Hadfield refers to are members of the Multilateral Space Medicine Board (MSMB), a body of representatives from the U.S., Canada, Europe, Japan and Russia who judge the medical fitness of astronauts to go on missions.

Hadfield’s medical problem stemmed from an appendectomy he received when he was 11. Scar tissue from the childhood operation caused a blockage of his intestines in 1990, he discloses, sending him into agony while he was vacationing near Sarnia, Ont.

Hadfield underwent surgery at that time to remove the blockage, and quickly resumed the career path that eventually led him to space.

But in October 2011, in the midst of his preparations for Expedition 35 to the ISS, Hadfield began feeling stomach pains. Doctors recommended conventional surgery to uncover the problem. But Hadfield feared such an invasive operation would derail his preparations; he instead sought laparoscopic surgery from Dr. Patrick Reardon, a leader in the field whose patients include Barbara Bush, the former U.S. First Lady.

Reardon discovered a four-centimetre adhesion (gluey scar tissue) at the site of the 1990 surgery that was pinning Hadfield’s intestines to his abdominal wall, and the physician quickly repaired it.

Still, some doctors at NASA worried that Hadfield might suffer complications in space from Reardon’s relatively new procedure, and made their thoughts known to the Multilateral Space Medicine Board, Hadfield writes. In January 2012, just 11 months before lift-off, the board asked him to submit to its “quick look” option.

Hadfield says and his wife, Helene, found the request “idiotic” because they’d researched medical literature on Reardon’s procedure and found no cases of complication—and because he believed it would create more risk than it would alleviate.

“Like any surgery, the procedure that was being proposed would introduce significant new risks,” he writes. “I might have an adverse reaction to general anesthetic, for instance, or I might develop an infection, or any number of surgical errors might occur—and any one of those things could then eliminate me from space flight.”

If that happened, Hadfield says, the risks and complications would multiply. For his expedition to proceed, NASA would be forced to swap him out for another astronaut who couldn’t possibly train in time for his duties. Moreover, he was the designated backup astronaut for a mission headed to the ISS in July, a role for which there was no immediate replacement.

So he refused, triggering what Hadfield describes as a “Kafkaesque” journey through “a bureaucratic quagmire where logic and data simply didn’t count.”

“Internal politics and uninformed opinions were what mattered,” he says in the book. “Doctors who hadn’t ever performed a laparoscopic procedure were weighing in; people were making decisions about medical risks as though far greater risks to the space program itself were irrelevant.”

In a rare show of frustration, he chides the Canadian Space Agency for its “too-Canadian” reluctance to try to influence the medical review process in his favour.

Only in March, just as the Multilateral Space Medicine Board was set to rule on whether it would demand the surgery, was the crisis resolved. A single member of the Multilateral Space Medicine Board recommended an ultrasound to see if there was any new build-up of scar tissue at the site of the 2011 operation, Hadfield writes. To his enormous relief, he passed.

The result cleared the way for a mission that yanked space exploration back into the public eye: the 54-year-old’s tweets and live broadcasts during his five months on the ISS turned him into a social-media phenomenon, while a video he made singing David Bowie’s hit “Space Oddity” while floating around the station went supernova, garnering nearly 18 million Youtube views to date.

Hadfield retired from his position with the Canadian Space Agency shortly after returning to Earth. On Oct. 8, the University of Waterloo announced that he had accepted a position as a professor of aviation the school’s sciences faculty, where he will conduct research into heart health. Specifically, he will look at why some astronauts are prone to fainting spells when they return to Earth.

Hadfield says he learned a lesson from his dispute that he took to space, comparing it to “out-of-control” tests military pilots perform on fighter jets.

“[I was] working a serious, complex problem while in freefall,” he says in the book, “professionally, without losing my focus on the true goal of the mission: making sure our crew was ready for space flight whether I was going with them or not.”