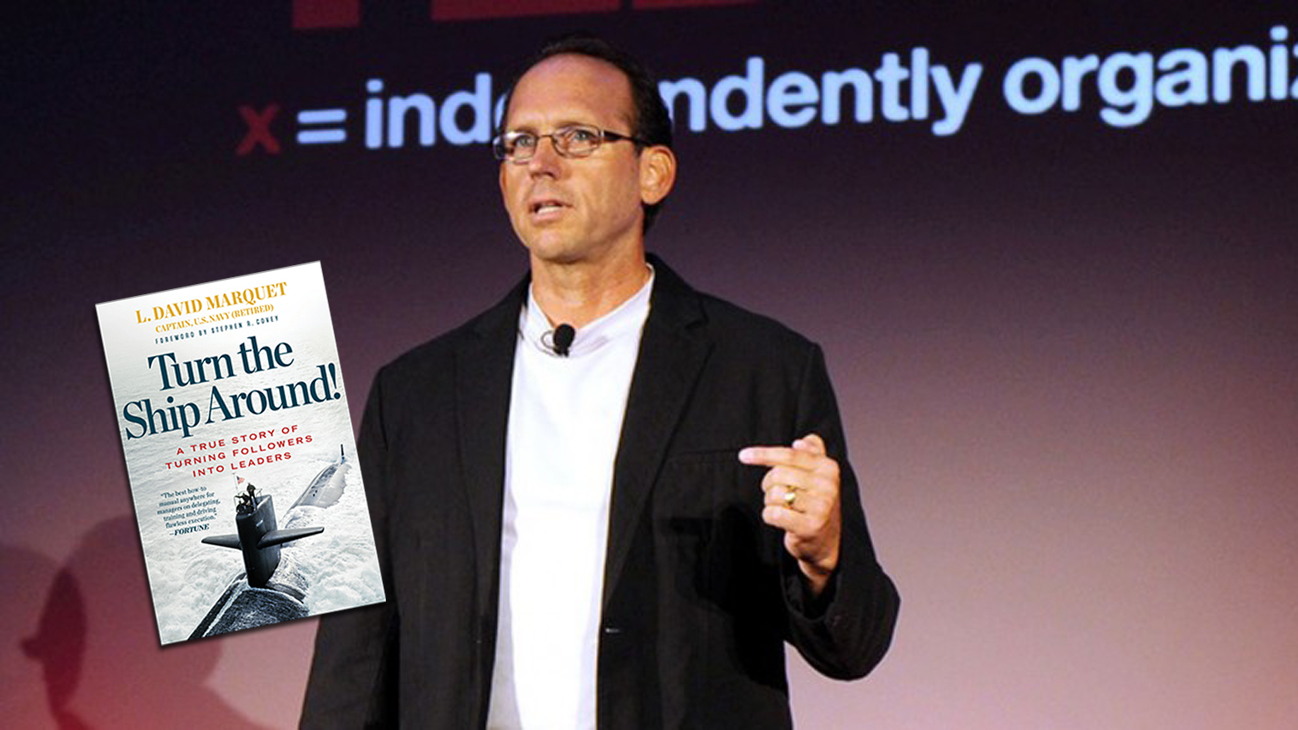

Retired US Navy Captain turned leadership-expert David Marquet single-handedly “turned his ship around” when he became captain of the USS Santa Fe, a nuclear powered submarine which had a crew ranked dead last in retention and operational standings. By treating his crew as leaders, not followers, Marquet’s sub went from “worst to first.” The author of the bestselling new book, Turn The Ship Around: How to Create Leadership at Every Level, Marquet takes a look at the recent spike in serious problems on cruise ships, and suggests the possible reasons behind this troubling trend:

Senator John D. Rockefeller has written to Carnival Cruise lines CEO Micky Arison expressing serious concerns about Carnival’s safety record. In the letter, Senator Rockefeller cites a Coast Guard report listing 90 serious events in the past 5 years on Carnival ships including groundings, collisions, allisions, fires, propulsion and electrical system failures. The most significant accidents this year have been the Carnival Triumph engine room fire and 5-day stranding in the Gulf of Mexico, the Carnival Dream generator failure in St. Maarten, and the Carnival Legend propulsion casualty and delayed return to Tampa. Overshadowing these was the Costa Concordia grounding last year with the loss of 32 lives.

Launched between 1999 and 2008 and weighing an average of 108,000 tons, these four ships are some of the biggest and newest in the industry. It isn’t the old ships that are failing; it’s the new ones. Why is that?

These are problems of resilience.

The first cruise ship to top 100,000 tons was the Carnival Destiny launched in 1996. It took 62 years from the launch of the Queen Mary in 1934 for cruise ship size to go from 81,000 tons to 100,000 tons but there are now 52 operational cruise ships over 100,000 tons and 16 more under construction.

With the recent spurt in size has come additional complexity. As ships and systems become more complex and more interconnected, the potential of cascading casualties increases — think of the power outage in 2003 that dropped power to 55 million people. It was only because the power grid is interconnected that so many people lost power.

There are two aspects to resilient ships: design resilience and organizational resilience.

By necessity, navies have known how to design resilient ships for years. The elements that make a ship more resilient are also more expensive. They involve redundant components, spare capacity, powering equipment from independent power systems, and selective breaker set points that isolate smaller faults quickly before larger portions of the system are affected. These practices are well defined and could be implemented for additional cost.

Less well-defined are the organizational practices for resilience.

Most cruise ships are run in a top-down, hierarchical manner. Autocratic captains issue orders and subordinates are expected to follow them. Captain Schettino of the Costa Concordia is the archetype. With these structures, compliance, not critical thinking, is the desired organizational behavior. Fragility results because the top-down structure propagates errors. Subordinates are reluctant to speak up even when they know the order is wrong.

Another cause of fragility in these systems is less obvious. Cruise ships, along with all organizations, share a common problem: separation of information from authority. Employees “at the edge” that interface directly with the customer, client, or with nature (the machinery) are the first to sense changes in the environment and have the most nuanced understanding of the customer, client or nature. They know what is going on but don’t have the authority to act fully. Authority rests with officers and executives up the chain of command.

The approach has been to develop communication systems that move the information to the authority. Decisions are made by those in authority and are transmitted back down to the employees who act on them. In addition to the delay and translation problems that this introduces, two critical components in this system are fragile: the communication paths that must transmit the information and the executive(s) that must make the decision.

A familiar example of how this system fails was the Fukushima reactor disaster in 2011. By TEPCO company policy, the site manager did not have the authority to vent the reactor containment buildings. This decision needed to be made by the company president. When the tsunami disrupted the emergency cooling pumps and the reactors began to overheat, the on-site personnel had the information that venting was required, but not the authority to act. The communication systems were disrupted, preventing transmission of the information to authority and this resulted in a several hour delay in venting the reactor containments.

A more resilient approach is one where the authority is pushed to those on the edge with the information. In the Fukushima case it is clear how this would have improved the response to the crisis but it is a better approach in non-crisis situations as well. Communication systems are used to transmit actions taken but the disruption of communications does not stop action, it only stops knowledge of the action by those removed from the scene.

Some wish they could awaken this self-acting structure during crises within a normally top-down bureaucracy but it doesn’t work that way. People who normally act as followers are less likely to step up into decision-making roles if they haven’t practiced making decisions during non-crisis periods.

The difficulty is to properly understand the conditions under which employees on the edge will make decisions aligned the organization’s goals and achieve unity of effort. This is the challenge of creating resilient systems. Until the cruise ship industry develops resilient systems based upon people, these problems will continue.