Breakthroughs in manufacturing and materials are so significant that they describe entire historical periods, from the Bronze Age to the Industrial Revolution. Manufacturing is on the verge of another epic rewrite, fueled by technology, along with changes in consumer patterns and capital markets.

“It’s a new frontier,” said Brian Heckler, national sector leader for industrial manufacturing at KPMG.

“There’s this trend of connected products and processes. Mass computing power. Virtually limitless broadband allowing us to capture data. New materials. New ways to design and produce products. All these things are coming together.”

This is another chapter in what we’re calling The Great Rewrite. The premise is bold: We’re amid the largest era of institutional change in history, a reformatting of the planet’s operating system. What is happening goes beyond innovation as we used to think of it, or single-market disruption. Changes coming via this rewrite are poised to alter pretty much everything in their wake. They will ripple across industries and institutions, fundamentally changing the way our species lives. They will create new industries, force the hand of markets, and set us on a path of deep upheaval to the status quo.

In industrial manufacturing, the rewrite is just beginning. Machines that can sense surroundings and communicate digitally are transforming the factory. Smart equipment tracks its work and feeds data into the cloud. Imagine a “digital thread” that lives with its product throughout its life. As a car comes through the factory, the performance of every machine that works on every component in the vehicle is tracked. When the vehicle is shipped, sensors monitor its performance on the road and its repair history. If a recall comes along, instead of having to call back an entire model year, or 10,000 vehicles that were produced in a given month, a carmaker can pinpoint just the 15 vehicles made when a particular machine tool was cutting too fast and caused the metal to fatigue.

Automation is rewriting manufacturing geography, letting manufacturers set up smaller factories closer to materials or customers. Having a single factory to the world in a low-cost location isn’t ideal anymore. Wages in China and India have risen, and the factories are far from most customers. They can return closer to home when machinery helps lower labor costs in more developed regions. That doesn’t have to mean eliminating human workers. Machines that work in concert with employees — so-called co-bots — are gaining traction. Using sensors and machine learning, robots can be trained to mimic human actions and work around people.

Fetch Robotics develops self-guided helper-bots that can navigate a factory or warehouse floor to help employees move around products and parts. The bots can become a virtual, smart assembly line that tracks the flow of goods. Tying into inventory systems, the mobile bots become a hardware extension of enterprise-management software, going places where the software can’t — and often places that aren’t people-friendly either. Fetch CEO Melonee Wise says robots are best in environments that are “dirty, dull or dangerous.”

New manufacturing materials are literally rewriting the act of creation. In Seattle, startup Modumetal has developed technology for building super-strong metal alloys. The company applies electric current to metallic raw materials to alter their structure. Layers of the treated metal then bind at the atomic level in ways that can create desired properties, such as 10 times the strength of steel or improved corrosion resistance. It’s like super-high-tech plywood that could make vehicles lighter and help bridges stand up longer. The manufacturing process is less expensive than traditional ways of making metals and requires a much smaller footprint.

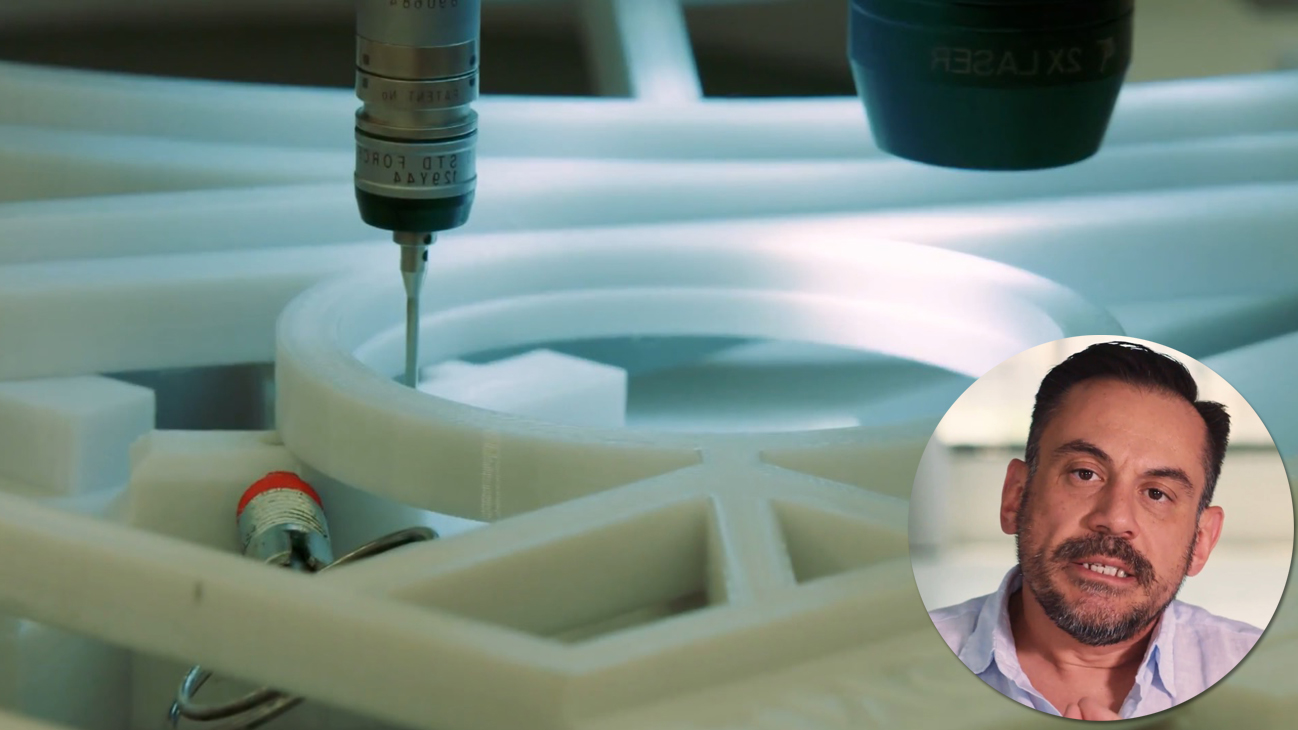

The rise of 3D printing brings almost boundless possibilities. Machines able to “print” solid objects can turn manufacturing inside out. Traditional manufacturing takes raw material and machines it, stamps it, cuts it, lathes it into desired shapes. It’s a subtractive process. Unused material is wasted. 3D printing is additive.

“It only builds what you need,” said Scott Crump, inventor of a 3D printing process and founder of Stratasys.

The 3D printing process can mix new composite materials at the output nozzle. Stratasys calls this “the age of digital materials.” An industrial 3D printer also can output a product that has multiple materials joined together — discrete areas of soft plastic, rigid plastic, metal — with no outside assembly required. That saves time and money. One Stratasys user, Japanese carmaker Daihatsu, this year will allow buyers of a new car model to select the color and texture of certain body details. The pieces will be “printed” in color on the factory floor. They don’t need to be painted in another location. There’s an aftermarket benefit to that, too: “When it gets scratched, it’s still the same color,” Crump said.

It is common sport these days for people to pontificate on whether or not what we are living through now is another Industrial Revolution. In truth, we believe what is happening is much more substantive and elemental. The end result will be a complete restructuring of the manufacturing sector that will affect not just the global factory floors, but everything that its downstream product touches as well.