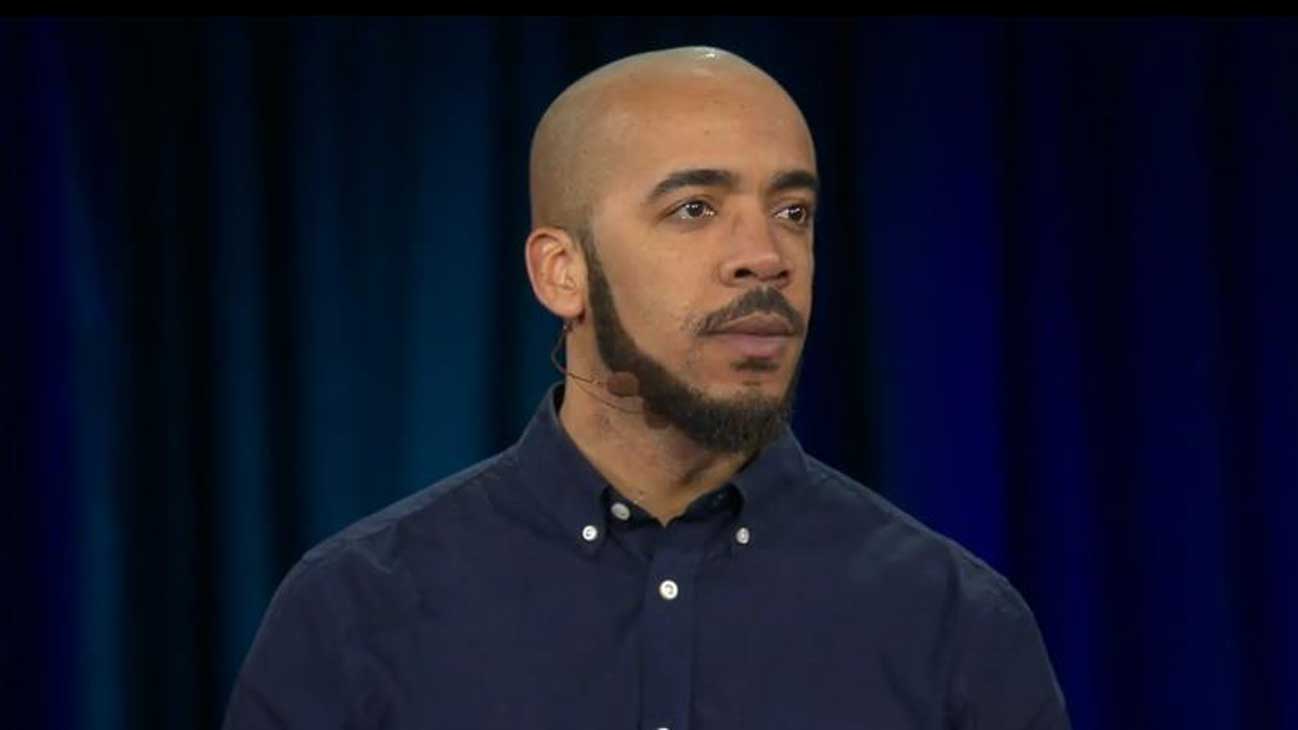

Clint Smith believes we all share a story, the human story. It’s in the telling, he believes, that we emerge as individuals and celebrate what we have in common. His TED Talk, a presentation of his spoken word poem, The Danger of Silence, has been viewed more than two million times, and was named one of the Top 20 TED Talks of 2014. Using his experience as an award-winning teacher and poet to share personal stories of justice, community, and education, his customizable art-form illuminates how we can all find the courage to create change, overcome challenges, and unite ourselves through the power of the collective voice. This recent article from Vox looks at the importance of Clint’s recent TED Talk:

It’s been said again and again and again — more frequently and publicly since unarmed black teen Trayvon Martin was gunned down by a neighbor who perceived him as a threat in 2013 — but probably for as long as black people have been in America: black kids just can’t do the same things white kids can. At least not if they want to survive.

A TED talk by Harvard University doctoral candidate Clint Smith is a recent, and especially thoughtful, personal narrative about this topic. Filmed March 2015 at TED2015, it’s titled “How to raise a black son in America.”

Smith starts by explaining what inspired him to think about this topic, making reference to the recent series of high-profile police-involved deaths of unarmed African Americans, which have inspired protests in Ferguson, Missouri, New York City, and Baltimore:

I’ve been thinking a lot about this lately, this idea of humanity, and specifically, who in this world is afforded the privilege of being perceived as fully human. Over the course of the past several months, the world has watched as unarmed black men, and women, have had their lives taken at the hands of police and vigilante. These events and all that has transpired after them have brought me back to my own childhood and the decisions that my parents made about raising a black boy in America that growing up, I didn’t always understand in the way that I do now.

Then he tells a story that has eerie echoes of the way 12-year-old Tamir Rice was killed while playing with a toy gun in Cleveland in November 2014.

For example, I think of how one night, when I was around 12 years old, on an overnight field trip to another city, my friends and I bought Super Soakers and turned the hotel parking lot into our own water-filled battle zone. We hid behind cars, running through the darkness that lay between the streetlights, boundless laughter ubiquitous across the pavement. But within 10 minutes, my father came outside, grabbed me by my forearm and led me into our room with an unfamiliar grip. Before I could say anything, tell him how foolish he had made me look in front of my friends, he derided me for being so naive. Looked me in the eye, fear consuming his face, and said, “Son, I’m sorry, but you can’t act the same as your white friends. You can’t pretend to shoot guns. You can’t run around in the dark. You can’t hide behind anything other than your own teeth.

Rice was doing almost exactly what Smith’s parents warned him about — being a kid and enjoying himself — when officer Timothy Loehmann shot and killed him within two seconds of pulling up to the area of the where he was standing.

The officer who called in the shooting thought Rice was 20 years old, according to BuzzFeed. “Shots fired, male down, black male, maybe 20,” he said.

The fact that Smith’s parents warned him about his behavior when he was just 12 is probably because they understood that, as Vox’s German Lopez has explained, it’s common for police to overestimate the age and size of black boys. Studies have indicated that both the general public and law enforcement officials tend to see them as less innocent. For police officers, this can result in overestimating them as a threat.

Until that changes, parents like Smith’s will have to take the same depressing approach to “how to raise a black son in America.”

Incredibly, Smith closes on a hopeful note, saying:

And I refuse to accept that we can’t build this world into something new, some place where a child’s name doesn’t have to be written on a t-shirt, or a tombstone, where the value of someone’s life isn’t determined by anything other than the fact that they had lungs, a place where every single one of us can breathe.