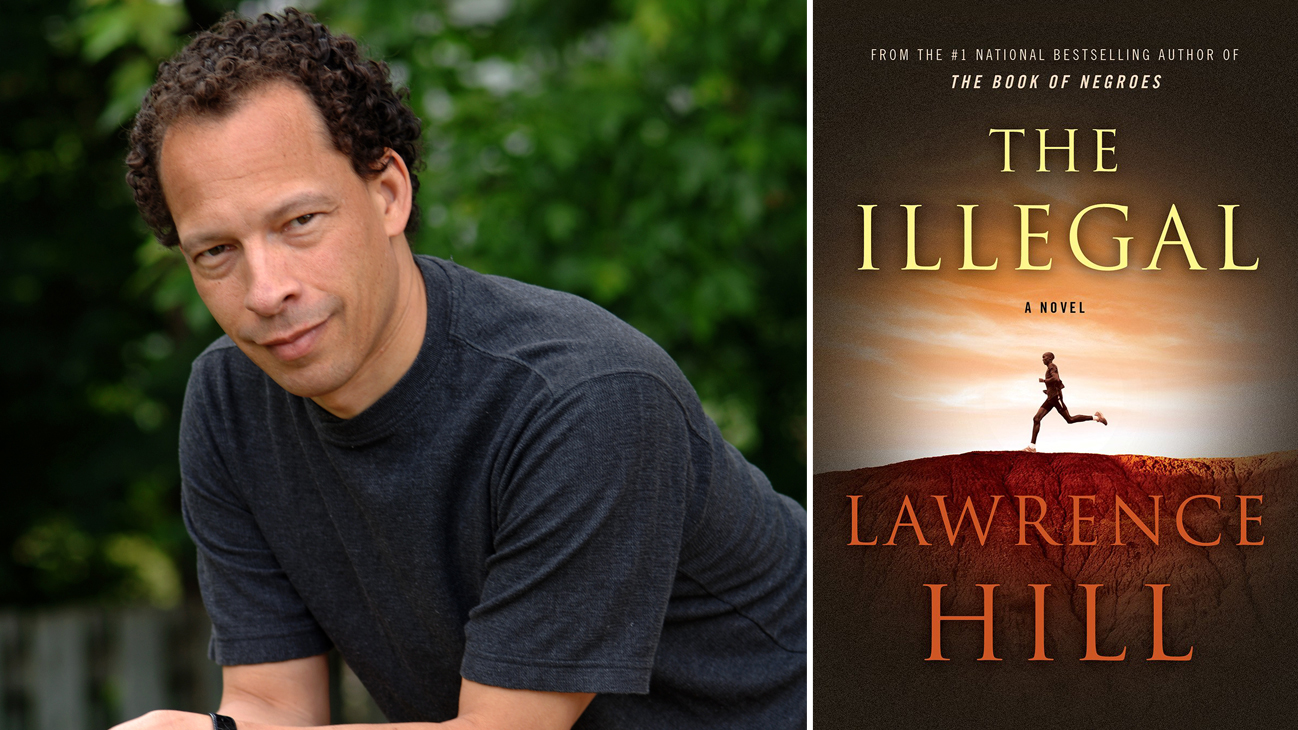

This is a book everyone’s been waiting for. Lawrence Hill’s third novel, The Book of Negroes, published in 2007, made the Canadian writer a household name, was made into a TV miniseries and won him a handful of awards. His new novel, The Illegal, was inspired by the stories of undocumented refugees and the fear they have of being deported, executed or persecuted. It’s out Sept. 8, but you can read an exclusive excerpt here:

Weeks earlier, after Keita’s first night in Clarkson — in a forty-dollar-a-night motel that did not demand ID because he paid cash up front — he had gone running in Ruddings Park.

A jogger recognized him as being of the same Faloo ethnicity and asked him to stop. Keita did so briefly, but he didn’t give his name or tell the man where he was staying. He listened, though, when the man told him not to travel in cars. Not if he wanted to avoid the immigration cops. They stopped people in cars all the time, the man said, and always demanded the national citizenship card. If you didn’t have it, they detained you until they could figure out where to deport you. Some people, he said, spent years in detention centres.

Keita thanked the man and said he had to keep moving. The man asked if he could run with Keita, just for a kilometre. He hadn’t run with anyone since leaving Zantoroland, he said, and he missed it. Sure, Keita said. He began running again, slowly to accommodate the fellow.

“So,” the jogger said, “have you heard of ZRA?” Keita said he hadn’t.

“It’s Zantorolanders Refugee Association. We want the government of Freedom State to hear our voices and to stop deporting people who are found without papers.” The jogger tapped his shoulder familiarly, like a friend might have done back home. “We need people in the movement.”

Keita nodded noncommittally.

“By the way, you run beautifully. Are you an elite marathoner?”

“I was. Now I’m just running to stay alive.”

“You could be a role model for our cause.”

“Sorry,” Keita repeated, “but I can’t help you right now.” And with that, he accelerated and left the jogger behind.

Keita was heeding the advice not to travel by car. Though his muscles were aching, he was sitting at the back of a bus in the Buttersby station, waiting for it to depart for Clarkson. He had killed several hours in the pub, where he sat in a corner, facing a wall, nursing tea and shepherd’s pie and hoping to avoid attention. Nobody knew his name or a thing about him, or cared if he was cold or hungry or afraid, but he feared that everyone noticed him.

Keita had boarded the bus the minute the doors opened. The less he was in public view, the better. He chose a window seat near the back. He had barely sat down when a boy — perhaps only twelve years old but travelling alone — took the seat beside him.

To take his mind off his troubles, Keita had turned on his iPod, put the buds in his ears and listened to a country song about a man with a broken heart.

I got the gotta have you

God I want you

Don’t you wanna love me blues

Wait all day for you to call my name

But baby baby baby baby

You ain’t got the blues the same

No

You ain’t got the same.

Keita found it odd that here, in one of the richest nations of the world, bad grammar seemed acceptable in music. Still, the words and music were catchy, and he hummed along until a woman across the aisle gave him a nasty look. He stopped and unplugged the iPod. He had to be careful. One did not hum or sing in public in Freedom State — neither while walking around the street nor while sitting on a bus. People in this country took it as a sign of mental imbalance. To Keita, that itself was insanity.